Editor’s Note: We met the three brothers that make up Butterscotch Shenanigans at GDC this year. When we found out about the incredible story behind their studio and the motivations behind shifting gears to their current project, we wanted to share it with everyone. However, since it involves illness, family, and other things which we honestly just don’t feel like we could ever do justice reporting on, we did the only thing that made sense- Offer them a platform on TouchArcade to write about the experiences that have led to the development of Crashlands. What you’re about to read is the first of a series of articles by Sam Coster as he fights for his life while developing the game he always wanted to make with his brothers, Seth and Adam.

Cancer is a great clarifier. It stripped out all the petty, superfluous aspects of life and demanded just three things when it struck me in 2013: survive, find meaning, and figure out how to look good bald.

This is the story of Crashlands, a massive 2D action-RPG crafting game I’ve been working on with my two brothers since I was diagnosed at the ripe age of 23 with Non-Hodgkins Lymphoma.

Prelude to Crashlands

It was June of 2013, less than a year from the time my brother Seth and I quit our jobs and started Butterscotch Shenanigans. In those first 8 months we created a critically acclaimed financial disaster (Towelfight 2) and found our first bit of success with Quadropus Rampage. The game didn’t get much attention on iTunes, but developed a sturdy enough following through Google Play that we saw our first ounce of income.

Quadropus’ launch also signaled the arrival of an odd, repeating daydream for me – when I walked into a room I’d occasionally see in my mind’s eye a dragon, composed entirely of blood, emerge from my chest and burst through a nearby wall. It was weird (OBVIOUSLY!), and I told Seth about it the third or fourth time it happened, sometime in mid July. We both agreed it was strange, and then went back to fulfilling support requests and patching Quadropus.

A few weeks later the support issues with Quadropus died down, so we decided to get to work on the next project. Our previous titles were born from game jams – 48 hour development sprints based on themes – so we hit our desks and began jamming out prototypes for our Next Big Thing.

Design discussions traditionally took the shape of long-form improv. Seth would say something like “THE MAIN CHARACTER SHOULD BE A CEPHALOPOD!” and I’d say “YES, AND IT SHOULD HAVE A GLORIOUS BOOTY!” and he’d say “YES, ALSO YOU SHOULD BE ABLE TO FIGHT ENEMIES USING A GOAT AS A SWORD!”

This would continue until we were both content with the level of absurdity in front of us. It was magic.

Only now, as we sat down to work, something had changed. Our jam sessions exhausted me. I was irritable, snappy, and tired. Design problems no longer felt like challenges, but obstacles. We scrapped game after game – some lived for hours before hitting the deathbin, others took weeks to finally keel over. Seth grew worried that I had fallen out of love with game dev, and I wondered why I was finding him so damn annoying.

Energy leaked out of me like I was an overly aggressive free-to-play title – only I had no one to pay 99 cents to to get it back.

Desperate for something to shed my insufferability, we concocted the Butterscotch Jam. It was a 5-day event, during which we produced five games, each in less than eight hours. It was meant to reinvigorate me and let us find the seed of our next title. At its conclusion we picked Extreme Slothcycling, the first of the five games, and began work in earnest. Seth seemed happier, too.

Desperate for something to shed my insufferability, we concocted the Butterscotch Jam. It was a 5-day event, during which we produced five games, each in less than eight hours. It was meant to reinvigorate me and let us find the seed of our next title. At its conclusion we picked Extreme Slothcycling, the first of the five games, and began work in earnest. Seth seemed happier, too.

And then I started to sweat.

The dragon arrives

I started going to bed earlier and sleeping later. My coffee consumption ramped to 2 liters each morning, but I still had to nap by 2pm. I started shedding weight and my left pectoral swoll up like Schwarzenegger. Fevers began rolling in daily at 5:30pm – each culminating in a 3am night sweat which drenched my sheets and woke me up, shivering. A lump appeared on my left chest wall, just underneath the armpit, and grew to the size of a lemon. My jaw occasionally went numb, and my body felt heavier and heavier.

I used WebMD and self-diagnosed my symptoms as Lyme disease. I went to a clinic. They looked me over, said it was viral, and gave me headache medicine. The blood dragon daydream was now hitting me every few hours. I suddenly felt like something was very, very wrong, so I called an Infectious Disease doctor, whose office said they wouldn’t be able to see me for at least a month because all the appointments were booked up but I compromised for an appointment with a Physician’s Assistant the next day, confident that I could freak her out enough to get the Infectious doc to take a look, and when she came in I told her I had Lyme and joked with her about the day and she asked for my shirt to come up and when I took it off she saw the lump and her eyes briefly flashed fear and I swear I could feel her stomach drop and she said she needed to grab the doctor which is exactly what I wanted but also I realized exactly what I did not want and the doc appeared and copped one feel on my perky pseudo-breast and exhaled deeply and dropped verbal napalm on me.

“This is going to sound strange, but I’m certain that’s cancer.”

Endless runners mean nothing

The next week was a flurry of surgical and bone marrow biopsies, tests and scans. At the end of it all I came out with a diagnosis – T-Cell Rich, Large B-Cell Lymphoma, stage 4b. I lost 22 pounds prior to diagnosis, 12% of my body weight. The scans showed I was more cancer than man, and that if I had waited a month for my appointment, as directed, I may well have died.

The first round of chemotherapy brought with it a release from the anxiety of dying and a surge of energy. The exhaustion and semi-depression that gripped me lifted away, and I found myself with a reservoir of energy so deep I scarcely knew what to do with it. Even under the effects of chemo my body felt so good I couldn’t believe it. Aside from the whole having-cancer thing I felt great.

Seth and I sat down the day after treatment and filled the whiteboard with design musings for Slothcycling. The process stumbled forward as we finished the roadmap for what needed to be done, but both of us left feeling uninspired. So much had happened in the short 2 weeks since we’d last looked at the project. We both felt like we were in a different place, and we were.

We needed to work on something that would generate meaning for us, as a studio and family. And that something sure as hell wasn’t an endless runner.

Seth left for the night and I began daydreaming. I wanted to build something big, something more like a world than a game. Something that I could escape into. I wasn’t concerned with market viability or monetization schemes. I was singularly concerned with making something that would emotionally sustain me through treatment.

I fired up Game Maker and prototyped the equivalent of a Roomba picking up leaves. The vision for a wild world, full of interaction and absurdity, started percolating as chemo-induced exhaustion returned. I went to sleep.

Seth arrived the next morning, ready to crank on Slothcycling. When he launched into a design point I stopped him and said :

“Seth, I don’t want Slothcycling to be the last game I make before I die.”

A bit melodramatic, perhaps, but I had a Roomba to sell.

I opened the project file and turned my prototype over to him. He played quietly, picking up leaves, while I spun the vision. I told him we’d build a world, somewhere I could escape to while I was in the hospital and going through this bullshit, somewhere we could pour months of rage and joy and frustration and everything else into. It’d be like Don’t Starve meets Diablo meets Pokemon, but not. And when I was better the game would be done, we’d share it with the rest of the world, and it would be a piece of armor for others to slide into when real life just needed to fucking be okay.

… also there’d be a one-legged cow hippo and you could milk it.

Seth collected ten leaves. They popped and turned into sandals. He looked at me with that mix of brotherly love and exasperation and said, “Alright, let’s get to work.”

A world of meaning

Two months later I stayed in the hospital for my first dose of Methotrexate, a drug so potent they give it to you, let it sit in your body for a short time, and then give you a ‘rescue-drug’ designed to stop it from working. It kills everything it touches and turns your bathroom into a biohazard zone. Literally. Anywhere you pee is under quarantine. The only way you can get out of the hospital and go home is by peeing it all out, a measured process that can take between 4 and 8 days.

The first day of this joyful process, Seth called and asked if he should come over for a visit. I was up, wheeling my drug-toting IV pole around the room, which was plugged into a catheter surgically implanted in my chest. I had just finished drinking my 7th liter of water (I’d later learn that this doesn’t help the drug leave faster, pro-tip) and had been stabbed in the back earlier in the day for a spinal fluid cancer-check. I told him, “No, don’t visit. But I do want to garden. Finish that seed bomb and GET ME A BUILD!”

He chuckled and 45 minutes later I found myself not in a hospital bed, full of poison, but in Crashlands, with several neat rows of Logtrees sprouting outside my base.

Each asset we created for Crashlands over the following months felt like a defiant middle finger, waved in the face of that dragon. Their design and creation helped me endure the bone pain, nausea, and other cancer-related grievances that cropped up, and gave Seth a sense that he was helping. Crashlands was our coping strategy writ large, a mindful sublimation of all the comic tragedy of getting cancer at the age of 23 for no goddamn reason.

When players garden, they are me in the hospital, receiving my first round of Methotrexate. When they drop their first Glorch, they are me, experiencing the first day-night cycle while sitting in a chair, wincing from bone pain. When they equip The Maw, the final weapon in the game, they are me, cured.

Briefly.

Pause

My treatments ended in March of 2014. Though the disease receded, a strange glow, like three burning embers, stayed lit in my left armpit. June, a short two months from my final treatment, left our family wrecked by stress. A regular PET Scan showed that those embers were brighter – more active – than before. An emergency biopsy was scheduled to ascertain whether or not my left armpit, the Center for Disease Out of Control, was what we feared.

I proposed to my girlfriend and the biopsy came back clean; no cancer.

Over the next few months we brought Adam, the eldest of our three-brother clan and a recently minted PhD in Molecular Biology, into Butterscotch. His arrival signified a change in perspective for us. Seth and I had always been so concerned with the studio dying (first 8 months) and then me dying (the next 8 months) that we had scarcely planned how to approach anything but the making of a game.

Adam gave us the gift of a future focus, and chipped away the latent anxiety and habits Seth and I created. We began planning for the future, laying the groundwork of BscotchID and setting up plans for the equivalent of world domination, in game dev terms. It was refreshing to think in intervals longer than 3 weeks, the time between chemo cycles. We ripped up and revamped nearly all of Crashlands’ systems, and found ourselves with a uniquely compelling game. We passed it to our alpha testers and they loved it.

The end of the game was finally in sight and everything was humming along. Then that lump reappeared.

Play

Last month I underwent another biopsy. Surgeons went through my left chest wall and stole several grape-sized lymph nodes from my body. Tests revealed what we’d hoped never to hear again; the cancer was back.

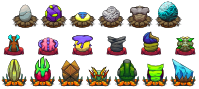

The first treatment, a 3-day, in-patient chemotherapy called R-ICE, left me wracked with nausea. I did the only thing I could think to do, given that I had no more girlfriends around to propose to; I made 18 creature eggs for Crashlands.

Bone-pain echoed through my spine and pelvis for a few days after I left the hospital. Between gritted teeth and shallow exhalations I made the Brubus, an alien race of stuck-up political bubble owls, for Crashlands.

Then my beard, a symbol that now graces our studio splash screen, fell out; so I whipped up six additional healing items, including Larvy Dogs and Spongy Podcake, for Crashlands.

I won’t see that beard again until September. Between now and then lies one more round of chemotherapy, several blasts of radiation and two stem-cell transplants. By the end of it all I will have spent 39 days in the hospital, received a new immune system from a stranger, and launched the game that kept me alive.

Working on Crashlands has been my outlet, my catharsis. This game has been my defense against blood dragons, poison, stab wounds and baldness. It stands as my family’s translation of adversity into something that will spin joy for thousands of people for thousands of hours.

It’s the biggest “FUCK YOU!” to cancer we can muster. And soon, you’ll get to play it.