![]() Retro visuals have become such a staple they’re beginning to feel like they’re modern again, but Shaun Inman‘s The Last Rocket ($1.99) proves it’s not just about the look, it’s about the entire aesthetic of the game, from the simple and easy to pick up gameplay to the sounds coming out it — retro is a design principle, not just a pair of pixilated pants.

Retro visuals have become such a staple they’re beginning to feel like they’re modern again, but Shaun Inman‘s The Last Rocket ($1.99) proves it’s not just about the look, it’s about the entire aesthetic of the game, from the simple and easy to pick up gameplay to the sounds coming out it — retro is a design principle, not just a pair of pixilated pants.

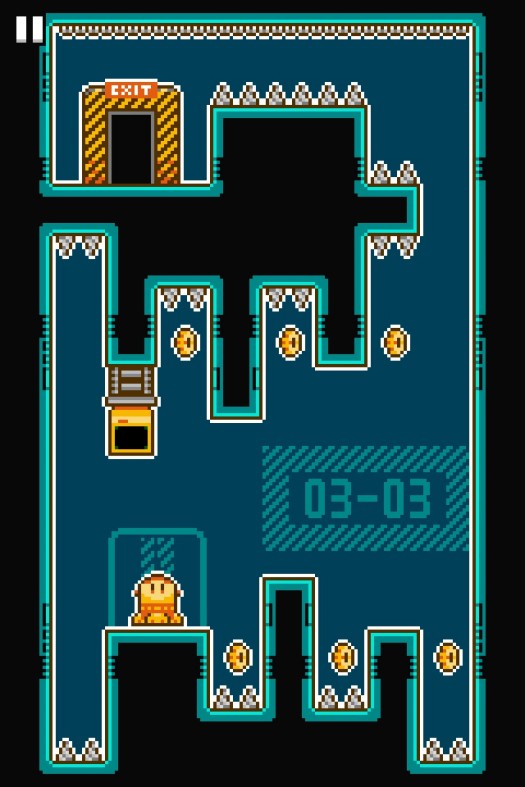

You play as a rocket — the last one, actually, in case the title didn’t clue you in — as you attempt to help an onboard computer collect gears and escape a ship before it tumbles into a star. The story doesn’t seem particularly important, but you’ll get different endings depending on how you complete it, and although you’re playing a mechanical rocket there is a whole lot of charm packed into that orange tube that will make you sympathize with its goal.

The Last Rocket has a lot in common with VVVVVV, where the primary control is restricted to the ability to flip from the ceiling to the floor, giving you no means to jump in a contemporary fashion. Control is handled by a single tap to jump, and another to change direction, then an occasional swipe to choose a direction or to walk. While the mechanics of The Last Rocket and even some of the puzzle design will look familiar to any masochist who’s chosen to subject themselves to the excellent, but brutally challenging VVVVVV, the game isn’t so much as a copy as it is playing with the same principles. If VVVVVV was a fetishistic iteration of Commodore 64 classics, The Last Rocket is the cousin inspired by the mechanic, but unflinching in the way it forges a different path.

That’s partially because The Last Rocket is optimized for play on iOS, which as we all have come to know, means the puzzles take place on a single screen and you can pick up items along the way to boost your score. Where this game differs is where it decides not to help you out along the way. You can’t replay any of the 64 levels, which are spread across eight different stages, and you have to continue on if you’ve missed a gear here or there. Punishing? Yes, but it falls in line with everything that The Last Rocket has going for it.

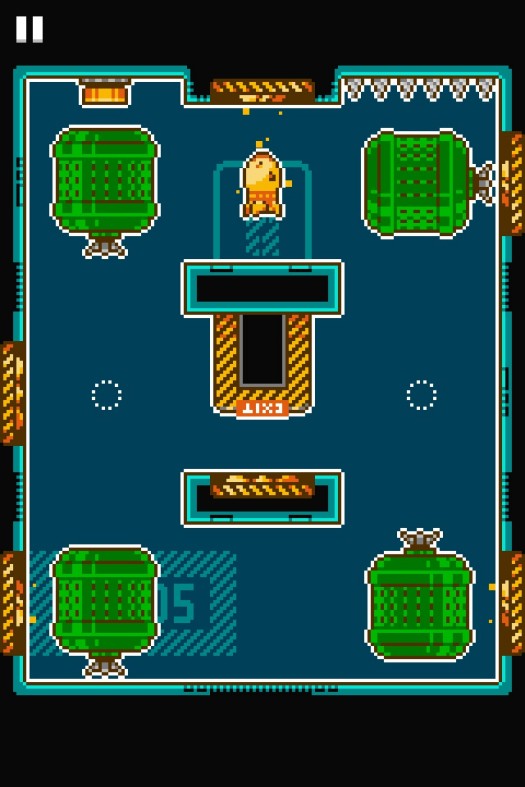

Each stage comes with its own gimmick. At first, it’s just learning the controls, but as you move on you’ll run into spikes, flames, moving platforms, disintegrating walls, hidden rooms and more. The bulk of the early levels tend to operate on one of two principles, either a puzzle or timing based screen. The later levels, especially in the seventh and eighth stages, work with both, where you need to be quick fingered and quick thinking — which is to say, you’ll often find yourself cursing at the game. Thankfully, it’s almost always your own fault as the controls, as simple as they are, work well.

The level design is worth noting for its ability to frustrate and teach you at the same time. While most of the early levels are geared toward teaching the mechanics, the game does a good job of introducing its elements slowly and largely without text. If you are having trouble, you can jump over to one of the computers at the beginning of the stage to get a tip. As for the frustrating parts, they’ll usually leave you cursing by the end, but they’re never so impossible you’ll want to quit forever — just for a few minutes.

As mentioned above, The Last Rocket comes packed with a clearly visible, easy to recognize 8-bit look, and the sound follows suit. The music works well at both drumming up nostalgia and fitting the mood, and if you find yourself particularly fond of any part of it you can play the soundtrack through the menu screen at any time.

What The Last Rocket does best is challenge both your reaction time and your brain. It’s not easy and it makes no concessions to modern ideas like level or stage selection, but it does offer a challenge you likely won’t be able to keep yourself away from for long. It’s well worth the price tag and you’ll find yourself so empathetic for the rocket’s goals that you’ll push yourself to finish it no matter how hard it gets.