My recent piece on Zombie Match Defense‘s (Free) postmortem, and me saying that it shows why decent games at $1.99 aren’t viable for developers any more, seemed to ruffle up a few feathers. This is surprising, because I figured that “it’s tough to make money at $1.99 unless you have a really special game and get lucky" seemed kind of like common knowledge. Like, humans breathe oxygen, water is wet, cheap paid games stopped being a good business strategy like 4 or 5 years ago. But I got a lot of pushback from smart folks, so I thought I’d elucidate why $1.99 – and really, cheap games in general – are a bad idea for developers, and why I implore developers to charge higher prices, and for players to financially support games they like, especially paid games that aren’t at bargain basement prices.

Mobile games being so cheap once made sense. This was back in the “gold rush" days when the App Store was new, few large companies were involved, and paid games were really the only way for developers to make money, so people that wanted to pass the time had to buy games. It was a legitimate gold rush scenario, and those who got in first tended to do well. Not everyone succeeded, but plenty found a good footing, and you had several stories of people like the iShoot ($0.99) developer who made over $600,000 in one month.

What happened is that as the App Store went on, developers started to figure out that they could price their games at ever lower prices in order to generate more sales, possibly even charting, with a potential increase in sales when returning to the original price point. This quickly became $0.99. Then, developers figured they could draw enough attention and word of mouth to their apps if they went free for a short amount of time, with the bounce back to paid generating enough sales (hopefully) to make up for the free promo time. And it was possible for even decent games of Zombie Match Defense‘s caliber to at least stay afloat, and allow these developers to build up a name for themselves and improve with future titles. Few people knock it out of the park on the first try. The upstart developers and hobbyists with some talent had a shot. And certainly, I’d like a market where developers who churn out solid games are doomed to making an okay living, instead of doomed to not even coming close to breaking even on their time and costs as they currently are.

But what happened was a combination of Apple allowing free apps to finally have in-app purchases, so apps could now monetize after going free, so what happened was that apps started to just straight-up appeal to people on the fact that they could get a ton of great experiences for no money whatsoever. And there’s a tiny marginal value to the average user between “game that is always free with purchases that may be necessary to facilitate your long-term enjoyment of the game" and “game that is meant to be paid that you can enjoy without ever paying, or with optional in-app purchases."

Plus, with more and more developers and publishers entering the market, suddenly the bar to good quality got a lot higher. It took more to stand out, and for many small studios trying to do professional work on limited resources, this becomes incredibly difficult. It also doesn’t help that the hardware kept improving, and Retina Displays forced developers to spend more time creating better and higher-resolution assets. This was a natural shift, but one that wasn’t making small developers’ lives easier.

Pricing also became supremely warped. What do you really expect from a game that costs $0.99? EA would regularly put its collection of games on sale for $0.99, especially around any random holiday it could justify putting games on sale for. Even today, this is an issue. You could’ve gotten Radiation Island ($4.99) on sale for a dollar at some point, and it’s a postively massive, open-world survival crafting adventure game that punches well above its weight class. Your taco stand selling already-cheap tacos doesn’t stand a chance if Rick Bayless is undercutting you, while offering Frontera Grill quality right next to you. But that’s the reality of the mobile gaming market. It’s weird.

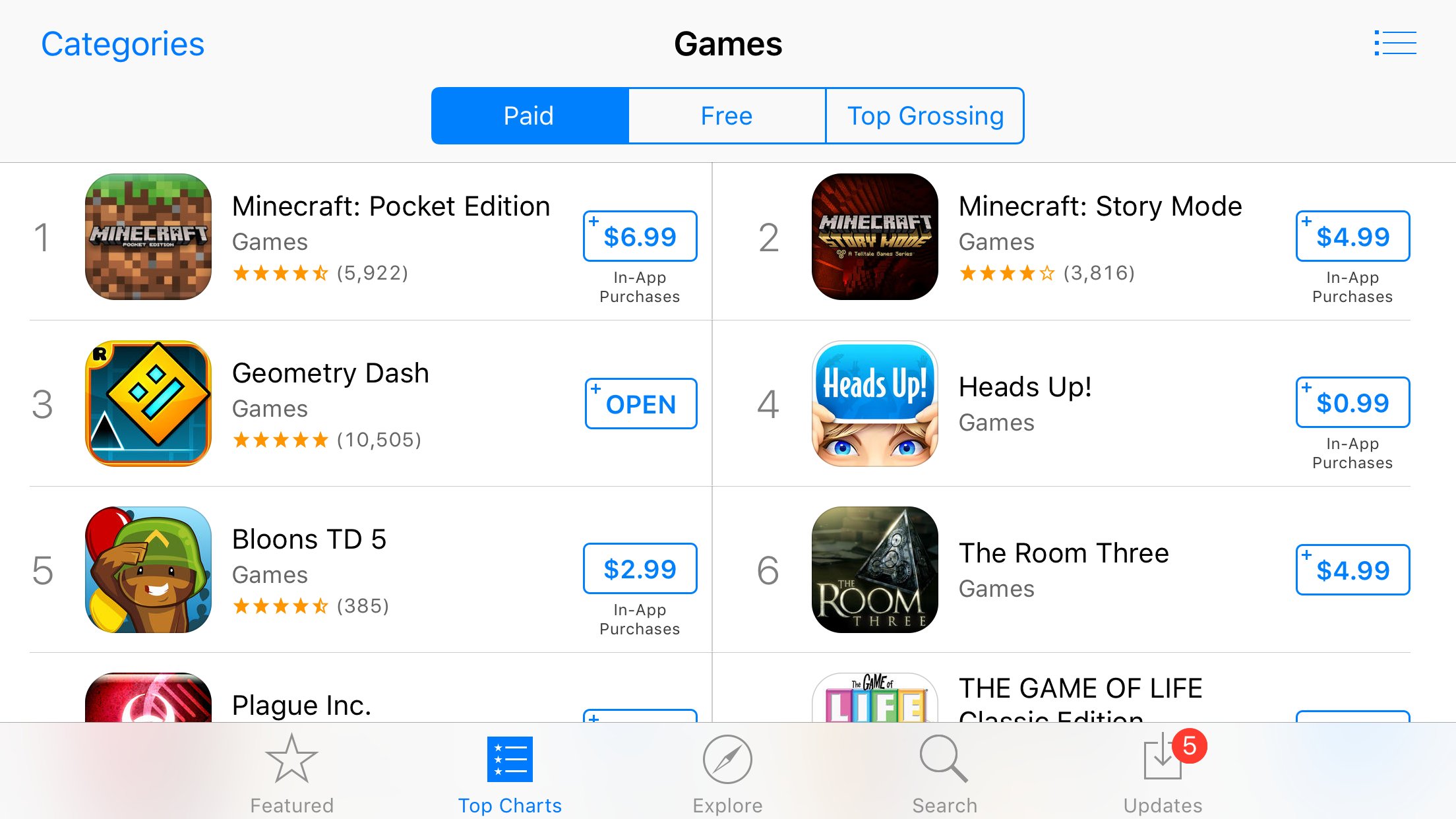

Oh and the market decided that it wanted free-to-play so badly that it took over the revenue from paid games over four years ago. The shift in 2013 was so dramatic, that on iOS, 92% of revenue came from free games with in-app purchases, according to a report from Distimo (now owned by AppAnnie). If you think that the balance of power has shifted, realize that according to estimates from ThinkGaming, Game of War (Free) makes over $1.46 million dollars per day. Minecraft: Pocket Edition ($6.99), the top dog among paid games? Game of War makes 45 times what Minecraft makes, and there’s several dozen games outclassing what it and any other paid game makes on the App Store.

Paid games lost.

There is a tiny chunk of change available to paid games, since consumers have decided that with mobile games, they don’t want to pay up front. And they don’t have to because there’s so many free games, and so many high quality ones. Meanwhile, someone who thinks that they want to sell games feels like they have to sell at low prices to a market that doesn’t want to buy them, And it’s not like the paid charts are full of fresh new games, they’re full of perennial hits like the aforementioned Minecraft. The majority of the paid games on the top chart? They’re games from before 2015.

So, you have a situation right now where a small professional developer’s chances at succeeding are to pray that their game is good enough to get Apple featuring (and on a slower week, I think Zombie Match Defense with its prerelease coverage and accolades, maybe gets the not-as-good-but-still-valuable end of the row feature on the App Store), manages to click well enough with prospective buyers in that limited time they have to sell the game to them. And maybe if their game is special enough, they can kick around the top charts to make enough money to be a self-sufficient, professional developer.

But you run the numbers, and they just don’t make sense. A game that’s $1.99 makes a developer about $1.40, let’s round up that penny on the 30% App Store cut. A developer looking to go full-time, to merely get above the 2015 US poverty threshold of $11,770 for themselves, would have to sell 8,407 copies of $1.99 games in a year. This is without including the expenses that game development entails, such as engine costs, computers, devices to test on, fees for contractors, and so on. And that’s just for a solo developer, any studio with multiple people trying to make money off of games has an even higher threshold to cross.

And you wonder why so many developers take side gigs or just work in their spare time from their day jobs.

Consider also that developers are competing on a global scale. Developers in countries like Vietnam and India, where a dollar goes much further, are also competing with them for space and featuring on the App Store. A dude in Vietnam made one of the most influential games of the last couple years, after all. And a developer in the USA might be at a bigger disadvantage compared to developers from the more socialist European countries, with bigger safety nets due to more expansive guaranteed minimum income programs. It’s a rocky playing field no matter what.

And as I said in my earlier Indiepocalypse article, maybe in these conditions, developers who want to go full-time as independent game developers should have a hit before they go off on their own. But, with that comes the catch-22 that it’s harder to make a game of great enough quality to stand out and be special when your waking hours are doing something besides making the game that gets you to the promised land of working without pants on.

But what about other price points? $0.99 still has the “it’s just a dollar, I can throw that away" feeling to it. This is not for a lot of people, necessarily; any money up front is a huge hurdle to cross. But $1.99 feels like a developer sitting in the worst middle ground. They’re asking for more than just an impulse buy. They can’t discount to a significant degree – going from $1.99 to $0.99 is hardly newsworthy, and not that much of a drop. Compare this to $2.99, where at least a $0.99 is a couple of dollars, and saving two-thirds of the original price. That feels more drastic. While I’ve struggled to find empirical studies done on this, I’d be willing to bet that $2.99 games on average gross more than $1.99 games.

Plus, at least with $2.99, there’s the need to sell fewer copies than $1.99 to get to the same point, and I think that external factors that drive a player to spend multiple dollars on a game mean that developers can shoot for higher and higher prices. Or at least they should. It makes no sense to sell cheap games when the mass market won’t buy at cheap prices. By selling a paid game, particularly one without IAP, a developer is putting a ceiling on how many users they’ll get, and how much revenue per user they’ll get. At least with higher-priced games, that ceiling can be raised. It’s why I’m such an advocate of developers of paid games selling at high prices for the platform: only so many people are gonna buy your game anyway. Why not get the people who do buy in to pay you a fair price for the limited units you do sell? And then, you have more flexibility for sales down the road from $4.99, $6.99, $9.99, and so on. But it is difficult to escape because, yeah, someone will undercut you with a game in a lower price bracket. But that feeling has to be ignored.

Developers can mitigate the risks by making multiple games in a year, but this presents its own challenges. On average, one would expect a game that was worked on longer to be better, of course. And making multiple games in a year is easier with a bigger team, but that requires making more money to keep everyone’s mouth fed. This doesn’t always mean that a multi-year opus is guaranteed to be better than a game made in a month, especially when we’re talking about the fickle nature of art, but a lot of the tweaking and adjustments to a game that can push it from good to great can happen with additional time. But it’s time that developers might not have.

The best analogy I can think of is the way that amateur athletes need to be reminded that most likely, they won’t make it to the pros. Many of them have that dream, but there’s only so many people who have the talent, skill, and drive to play professionally. It’s why you hear so many athletes talk about the people who said they could never do it, who always counted them out; because to be real? They had to do so for the people who needed to the grounding in the reality that their dreams are most likely unattainable. Only the strong survive.

Not everyone can make it in a tough market, and I’d rather be honest about how tough it is than to peddle the idealistic delusion that “everyone has a shot!" No, they don’t, and so it goes with game developers. Many of them need to realize that yes, they should work hard, but their endgame with game development needs to be to enjoy it and be proud of what they did, not for the checks from Apple to be what puts food in their mouths.

And for the developers who think that they have what it does take, that they have the talent to thwart me? People like Folmer Kelly, who always gets mad whenever I write something about this topic, and who I respect immensely for trying to prove the haters and doubters like me wrong? The thing is, there’s only so many people like him who can hustle enough to thrive in this market. But they do exist. They’re just the minority, almost a rounding error in a world of vast competition created by the death of scarcity. And I sure hope they go on and prove me wrong. Trust me, I’ll enjoy the games they make, I’m sure.

But what everyone needs to realize is that right now, on mobile in particular? Where there’s millions of games, thousands and thousands of developers, and the idea of value is so skewed that a fair price for the work of developers to sustain themselves is practically unattainable? It doesn’t work.