Hello, gentle readers, and welcome to the RPG Reload. This week, we’re starting a new project that will replace the monthly reader’s choice articles seen in the first year of the feature. That means that we will not be taking a look at a specific RPG from the App Store’s past this time around. Instead, we’ll be digging back a little farther. We’re going to be going into the history of handheld RPGs, from the paper age all the way up until the hardware of today. In total, this feature will span twelve columns, each one taking a look at a specific era in handheld RPGs. I hope you enjoy reading them as much as I’ve enjoyed researching and writing them! Please let me know what you think by commenting below, posting in the Official RPG Reload Club thread, or by tweeting me at @RPGReload.

Hello, gentle readers, and welcome to the RPG Reload. This week, we’re starting a new project that will replace the monthly reader’s choice articles seen in the first year of the feature. That means that we will not be taking a look at a specific RPG from the App Store’s past this time around. Instead, we’ll be digging back a little farther. We’re going to be going into the history of handheld RPGs, from the paper age all the way up until the hardware of today. In total, this feature will span twelve columns, each one taking a look at a specific era in handheld RPGs. I hope you enjoy reading them as much as I’ve enjoyed researching and writing them! Please let me know what you think by commenting below, posting in the Official RPG Reload Club thread, or by tweeting me at @RPGReload.

It should go without saying that tabletop, computer, console, handheld, and mobile games are all inextricably tied with each other in various ways. To consider how other platforms contributed to handheld RPGs in these articles would grow them well beyond the scope I’m able to deal with. I’ll be mentioning some influences here and there, but this is basically a disclaimer that I’m aware handheld RPGs don’t exist in a vacuum, in spite of the relatively narrow historical focus of these articles.

The History Of Handheld RPGs, Part One – The Paper Age

Like all RPGs, handheld RPGs owe a great debt to tabletop gaming. It’s my contention that the first things we can consider handheld RPGs are gamebooks, where the influence from Gary Gygax’s Dungeons & Dragons on many of the well-known titles ought to be clear to anyone. That being said, gamebooks themselves can’t be fully attributed to tabletop games. While many popular gamebooks use dice, persistent inventory, player statistics, and savings checks, some of the most popular lines don’t use any of those things at all. The famous Choose Your Own Adventure series from Bantam Books, for example, simply offers players choices at various points in the story. That’s an important part of modern RPGs, but the idea certainly predates the 1974 release of Dungeons & Dragons, its 1971 predecessor Chainmail, and even many of the tabletop war games that inspired them both.

Like all RPGs, handheld RPGs owe a great debt to tabletop gaming. It’s my contention that the first things we can consider handheld RPGs are gamebooks, where the influence from Gary Gygax’s Dungeons & Dragons on many of the well-known titles ought to be clear to anyone. That being said, gamebooks themselves can’t be fully attributed to tabletop games. While many popular gamebooks use dice, persistent inventory, player statistics, and savings checks, some of the most popular lines don’t use any of those things at all. The famous Choose Your Own Adventure series from Bantam Books, for example, simply offers players choices at various points in the story. That’s an important part of modern RPGs, but the idea certainly predates the 1974 release of Dungeons & Dragons, its 1971 predecessor Chainmail, and even many of the tabletop war games that inspired them both.

The first books that even thought to ask the reader to take an active role in the story were the Ellery Queen Mystery novels, a series of 10 books published from 1929 to 1936. They were pretty typical mystery novels except in one respect. Once all the clues had been dropped, the author would challenge the reader to try to guess the solution before the book did. It’s not much, and I’m sure most mystery fans had been doing it already, but for the book to address the reader directly and ask them to guess the ending was a pretty big step. Ellery Queen would go on to become something of a household name in the mystery genre, introducing many new writers to the English-reading public through the periodical Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine.

The next major contributions came from Argentinian author Jorge Luis Borges. He was an incredibly talented writer, and he particularly enjoyed playing around with the qualities of literature itself. Many of his works featured a writer as the protagonist or central figure, and two such stories in particular are of interest to this topic, both originally published in Spanish language in 1941. Examen de la obra de Herbert Quain (“An Examination of the Work of Herbert Quain“) told the story of an author whose book used branching paths to create multiple endings, while El Jardin de senderos que se bifurcan (“The Garden of Forking Paths“) is the story of a seemingly-nonsensical book that turned out to be a maze. The latter in particular almost perfectly predicts modern gamebooks, though in that story the readers had to try to piece together the correct order of the story themselves rather than be directed by page notes. It was meant to be a maze, after all.

The next major contributions came from Argentinian author Jorge Luis Borges. He was an incredibly talented writer, and he particularly enjoyed playing around with the qualities of literature itself. Many of his works featured a writer as the protagonist or central figure, and two such stories in particular are of interest to this topic, both originally published in Spanish language in 1941. Examen de la obra de Herbert Quain (“An Examination of the Work of Herbert Quain“) told the story of an author whose book used branching paths to create multiple endings, while El Jardin de senderos que se bifurcan (“The Garden of Forking Paths“) is the story of a seemingly-nonsensical book that turned out to be a maze. The latter in particular almost perfectly predicts modern gamebooks, though in that story the readers had to try to piece together the correct order of the story themselves rather than be directed by page notes. It was meant to be a maze, after all.

From here, we take an interesting detour into the field of education. The work of behavioral psychologists like B. F. Skinner in the 1940s and beyond had a major effect on many areas of our society. Skinner himself had many applications in mind for his research, but he was particularly interested in its uses for education. In the mid-1950s, he presented an idea called programmed learning, wherein the student would have to input an answer to a question using a special keyboard. If the answer was correct, they would proceed to the next one, but if it were incorrect, the student would be informed as to why and sent back to the same question. A series of educational books called TutorText were produced based on this idea, with the first installment, The Arithmetic Of Computers, published in 1958, and the last, The Game Of Chess, published in 1972. Technically speaking, these are probably the first books with an actual gamebook structure in the way we know it. The creators of the popular Fighting Fantasy series, Steve Jackson and Ian Livingstone, credit these educational materials for influencing the development of their gamebooks.

In 1967, a group of French writers collectively known as the Oulipo applied the idea of branching paths to fiction, giving it the name “tree literature". First used in the short story Un conte a votre facon (“A Story As You Like It“), this was a relatively simple implementation that was more experimentation than any sort of real commitment to the concept. Clocking in at only twenty or so passages long, it’s a pretty fun read, and its title certainly calls to mind the Choose Your Own Adventure series. For all of its ridiculous branches, the story can only end in one of two ways, with the reader satisfied and the author ending the story as a result, or the reader asking for more and being rebuffed by the author, who informs you the story is over. There were a few other experiments with the form similar to this, but for the purposes of expediency, we’re going to jump ahead to 1979, when two authors with an interest in really making a go of interactive fiction connected with Bantam Books and created a phenomenon.

In 1967, a group of French writers collectively known as the Oulipo applied the idea of branching paths to fiction, giving it the name “tree literature". First used in the short story Un conte a votre facon (“A Story As You Like It“), this was a relatively simple implementation that was more experimentation than any sort of real commitment to the concept. Clocking in at only twenty or so passages long, it’s a pretty fun read, and its title certainly calls to mind the Choose Your Own Adventure series. For all of its ridiculous branches, the story can only end in one of two ways, with the reader satisfied and the author ending the story as a result, or the reader asking for more and being rebuffed by the author, who informs you the story is over. There were a few other experiments with the form similar to this, but for the purposes of expediency, we’re going to jump ahead to 1979, when two authors with an interest in really making a go of interactive fiction connected with Bantam Books and created a phenomenon.

Edward Packard finished writing The Adventures Of You On Sugarcane Island in 1969, based on the sort of improvisational storytelling he would engage in with his children. It was rejected time and time again until it was finally picked up in 1976 by Vermont Crossroads Press, whose publisher at the time was a man by the name of R. A. Montgomery. Packard had two similar books published by a different publishing house, each one touting the fact that the reader could “choose your own adventure". You see where this is going. Bantam Books saw merit in the idea, the rights were transferred, and both Packard and Montgomery got to work on their contributions to Bantam’s new line of interactive storybooks, Choose Your Own Adventure. Kicking off with Packard’s The Cave Of Time, the series was almost an immediate smash hit with young readers. Bantam would go on to publish 185 Choose Your Own Adventure books between 1979 and 1998, when the series had more or less spent itself sales-wise and was put to rest. The total sales for the series counted up to more than 250 million copies. Even if you divide that by the rather large number of installments, that’s still an incredibly impressive number.

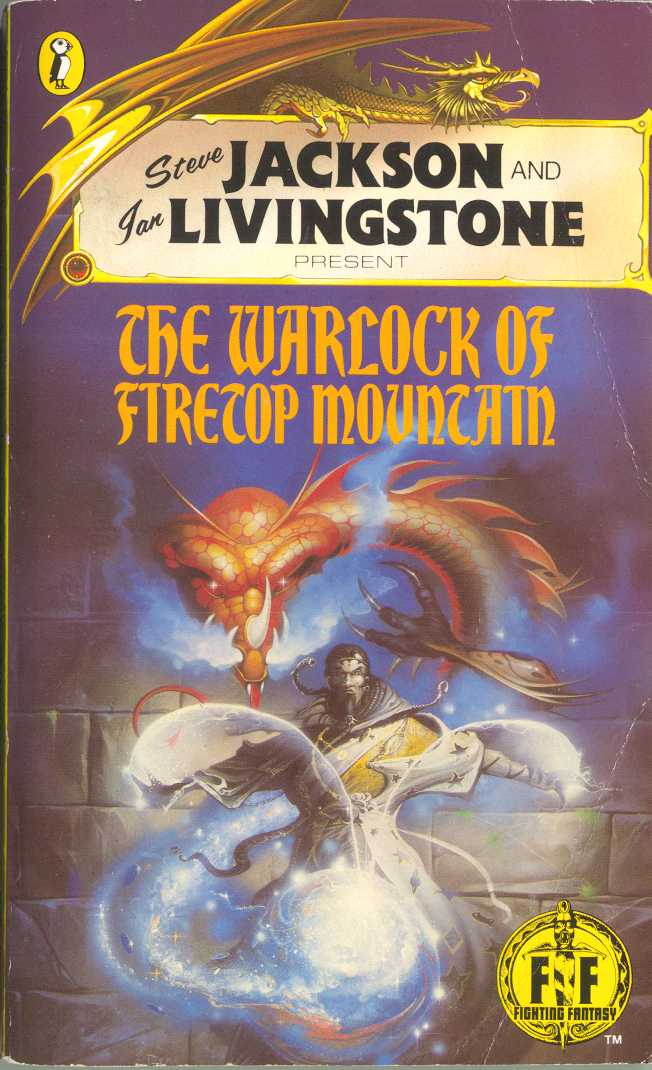

It’s hard to say if the recently-launched Choose Your Own Adventures books were on anyone’s mind when Games Workshop founders Ian Livingstone and Steve Jackson connected with a young Penguin Books editor by the name of Geraldine Cooke at their annual Games Day convention in 1980. At the very least, it seems unlikely given the timing and circumstances. Cooke was in charge of the sci-fi and fantasy lines at Penguin, which were in a state such that nobody seemed to care much what Cooke did with them. Livingstone and Jackson pitched the idea of doing a book that would serve to introduce newcomers to role-playing and its concepts. The book would take the form of a short solo game called The Magic Quest, which could be played with just a pencil, eraser, and a six-sided die or two.

It’s hard to say if the recently-launched Choose Your Own Adventures books were on anyone’s mind when Games Workshop founders Ian Livingstone and Steve Jackson connected with a young Penguin Books editor by the name of Geraldine Cooke at their annual Games Day convention in 1980. At the very least, it seems unlikely given the timing and circumstances. Cooke was in charge of the sci-fi and fantasy lines at Penguin, which were in a state such that nobody seemed to care much what Cooke did with them. Livingstone and Jackson pitched the idea of doing a book that would serve to introduce newcomers to role-playing and its concepts. The book would take the form of a short solo game called The Magic Quest, which could be played with just a pencil, eraser, and a six-sided die or two.

Solo games weren’t entirely unheard of at the time. The Tunnels & Trolls pen and paper system had a few solo adventures, with the first, Buffalo Castle, published in 1976. These adventures required the player to have a copy of the Tunnels & Trolls rulebook, however, along with a variety of other materials. Jackson and Livingstone’s book was self-contained and fairly simple to play. Cooke was convinced, but Penguin wasn’t. It wasn’t until the head of Puffin, the Children’s Publishing division at Penguin, took interest in it that things moved forward. Puffin was chasing ideas that could become playground crazes. They took a chance on Jackson and Livingstone and got exactly what they wanted, and then some.

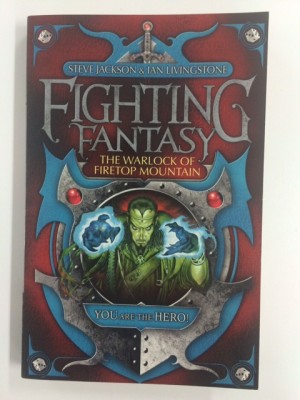

With the official greenlight, Jackson and Livingstone got to work fleshing out their idea. Over the course of six months, Livingstone would write the first half while Jackson wrote the last half. Newly retitled The Warlock Of Firetop Mountain, it released in August of 1982 and sold out its first printing within a matter of weeks. Jackson and Livingstone started working on their own individual follow-ups in the series that had been dubbed Fighting Fantasy, and when those released in early 1983, they sold out, too. Puffin had a serious hit on their hands, and as with Bantam’s success with Choose Your Own Adventure, it didn’t go unnoticed.

With the official greenlight, Jackson and Livingstone got to work fleshing out their idea. Over the course of six months, Livingstone would write the first half while Jackson wrote the last half. Newly retitled The Warlock Of Firetop Mountain, it released in August of 1982 and sold out its first printing within a matter of weeks. Jackson and Livingstone started working on their own individual follow-ups in the series that had been dubbed Fighting Fantasy, and when those released in early 1983, they sold out, too. Puffin had a serious hit on their hands, and as with Bantam’s success with Choose Your Own Adventure, it didn’t go unnoticed.

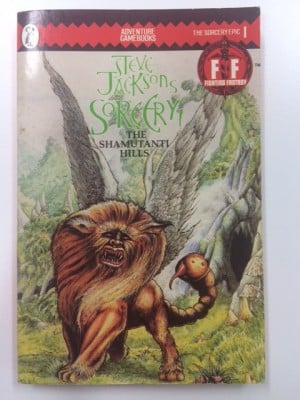

Fighting Fantasy‘s combination of interactive fiction and role-playing systems resulted in what I would consider the first true handheld RPGs, and it seems like they were far more popular than even Dungeons & Dragons itself for a time. They’re a little rough, and sometimes maddeningly difficult, but before the advent of Game Boy, they were a young geek’s dream come true. The series ran out of gas around 1995, with the 59th book, Curse Of The Mummy, being the last one for quite some time. Most of the books used the same basic rules, though there were twists here and there, particularly in Steve Jackson’s four-part Sorcery! series, which added magic and a rare persisting main character across its four books. The Fighting Fantasy series has since enjoyed a bit of a resurgence thanks to reprints by Wizard Books and the popularity of digital versions produced by Australian game publisher Tin Man Games and, in the case of Sorcery!, UK-based inkle Studios.

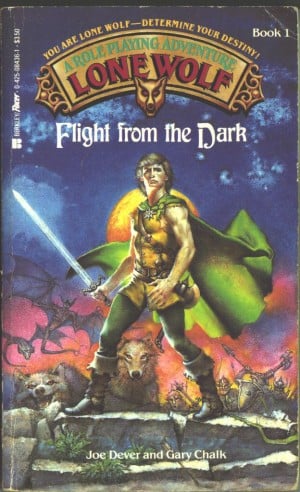

Moving back to the 1980s, it didn’t take long for competition to arrive. I’m not going to list every attempt, and I’m even going to be so bold as to gloss over Dungeons & Dragons publisher TSR’s short-lived venture into this new category. Instead, let’s jump right to the notables. Lone Wolf, a series written by Joe Dever and illustrated by Gary Chalk, added a bit more complexity to the formula. The first book, 1984’s Flight From The Dark, told the tale of a young warrior named Lone Wolf, the last surviving member of a group of warrior-monks known as Kai Lords. Kai Lords had special powers called Kai Disciplines, and the player was instructed to choose five out of a possible ten when they started the game. Along with this system, the other interesting aspect of the Lone Wolf series is that its main character persists through several books, retaining his skills, items, and progress. The series ran 32 installments split between two protagonists. The last new installment was published in 1998, but reprints have become fairly popular of late, especially in Europe. Like Fighting Fantasy, Lone Wolf is represented on iOS, albeit with a slightly more liberal interpretation.

Moving back to the 1980s, it didn’t take long for competition to arrive. I’m not going to list every attempt, and I’m even going to be so bold as to gloss over Dungeons & Dragons publisher TSR’s short-lived venture into this new category. Instead, let’s jump right to the notables. Lone Wolf, a series written by Joe Dever and illustrated by Gary Chalk, added a bit more complexity to the formula. The first book, 1984’s Flight From The Dark, told the tale of a young warrior named Lone Wolf, the last surviving member of a group of warrior-monks known as Kai Lords. Kai Lords had special powers called Kai Disciplines, and the player was instructed to choose five out of a possible ten when they started the game. Along with this system, the other interesting aspect of the Lone Wolf series is that its main character persists through several books, retaining his skills, items, and progress. The series ran 32 installments split between two protagonists. The last new installment was published in 1998, but reprints have become fairly popular of late, especially in Europe. Like Fighting Fantasy, Lone Wolf is represented on iOS, albeit with a slightly more liberal interpretation.

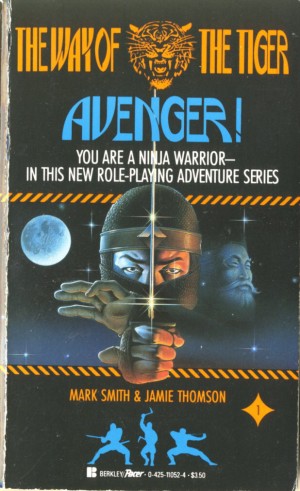

An interesting variation on the usual fantasy tropes came with the 1985 release of the first The Way Of The Tiger gamebook, titled Avenger!. It told the story of a ninja called Avenger, and is a wonderful slice of 1980s martial arts entertainment. The writing was quite sharp, the setting was fresh, and the combat system was actually pretty involved. The original series ran for six installments, finishing on a cliffhanger with the 1987 release of Inferno!. In the last couple of years, two more books were written to bookend the series and finally resolve that 25+ year hanging thread. Tin Man Games has committed to bringing the first six books to digital platforms, though no specific release dates are set as of now.

There are many more, of course, some based on licenses, many original, very few of which survived the 1990s. As the 1980s drew to a close, things seemed pretty rosy for the genre, but the apocalypse was just around the corner. Nintendo’s brand of console gaming was ruling with a mighty fist in the homes of children in North America and Japan. It was in 1989 when they released the Game Boy that Nintendo would successfully launch their invasion of schoolbags and playgrounds, the traditional homes of gamebooks. The first RPGs would arrive for the system surprisingly quickly, too. After fighting a good fight for a few years, even the most popular lines of gamebooks were limping along in sales by the middle of the 1990s. We’ll talk about the Game Boy’s story next time, but we’ll be bidding a farewell to paper gamebooks here. Gamebooks might not seem like much these days, but they were the original way for many of us to goof off in the library, and for that, I salute them.

There are many more, of course, some based on licenses, many original, very few of which survived the 1990s. As the 1980s drew to a close, things seemed pretty rosy for the genre, but the apocalypse was just around the corner. Nintendo’s brand of console gaming was ruling with a mighty fist in the homes of children in North America and Japan. It was in 1989 when they released the Game Boy that Nintendo would successfully launch their invasion of schoolbags and playgrounds, the traditional homes of gamebooks. The first RPGs would arrive for the system surprisingly quickly, too. After fighting a good fight for a few years, even the most popular lines of gamebooks were limping along in sales by the middle of the 1990s. We’ll talk about the Game Boy’s story next time, but we’ll be bidding a farewell to paper gamebooks here. Gamebooks might not seem like much these days, but they were the original way for many of us to goof off in the library, and for that, I salute them.

Shaun’s Five For The Paper Age

For each part of this series, I’ll be selecting five notable or interesting titles to highlight. If you’re looking to get a good cross-section of the era in question, these picks are a good place to start.

The Warlock Of Firetop Mountain – The first Fighting Fantasy is also one of the best, thanks to a super-powered team-up between Ian Livingstone and Steve Jackson. The Warlock who keeps a lair in the nearby Firetop Mountain has a treasure, and your character aims to get it. You’ll have to travel through the dungeons underneath Firetop Mountain, searching for keys and surviving dangerous encounters with monsters. Once you’re through the dungeons, you’ll have to deal with the Warlock himself. It’s a difficult game, though it has few of the instant deaths that fans of the Fighting Fantasy series would come to loath. I like how you get a taste of both Livingstone and Jackson’s design styles, making for variety not found in many of the other installments. It’s a bit generic, to be sure, but there’s nothing wrong with that when it’s as enjoyable as Warlock.

The Warlock Of Firetop Mountain – The first Fighting Fantasy is also one of the best, thanks to a super-powered team-up between Ian Livingstone and Steve Jackson. The Warlock who keeps a lair in the nearby Firetop Mountain has a treasure, and your character aims to get it. You’ll have to travel through the dungeons underneath Firetop Mountain, searching for keys and surviving dangerous encounters with monsters. Once you’re through the dungeons, you’ll have to deal with the Warlock himself. It’s a difficult game, though it has few of the instant deaths that fans of the Fighting Fantasy series would come to loath. I like how you get a taste of both Livingstone and Jackson’s design styles, making for variety not found in many of the other installments. It’s a bit generic, to be sure, but there’s nothing wrong with that when it’s as enjoyable as Warlock.

Lone Wolf: Flight From The Dark – Lone Wolf has a very unique feel to it, and it hits the ground running with this first installment. The world-building is simply excellent, doing a wonderful job of setting the stage for the adventures to come. While the first book isn’t quite as fun as many of the later ones due to Lone Wolf’s limited equipment and power, I can’t imagine taking this series on in any fashion save starting from the first. What I really appreciate about the Lone Wolf series is the complexity it manages while still being completely portable, even going so far as to feature random number tables for all you weird people who don’t carry dice with you everywhere. While I ultimately enjoyed the mobile Lone Wolf, I sure as heck wouldn’t say no to some straight adaptations of this series.

Choose Your Own Adventure: The Cave Of Time – Sure, it’s a lot less RPG-like than the other picks here, but it’s certainly no less significant in promoting the idea of playing games on the go. Plus, it’s about a cave that lets you time travel, a concept that author Edward Packard milks for all it’s worth. The choices are often random, having you choose between left or right without any context at all, and it’s not so much a story as it is a sequence of vignettes, but it’s pretty fun to blow through anyway. As a game, it’s pretty terrible, but as a plunge into the waters of nostalgia, well, it could be a lot worse.

Steve Jackson’s Sorcery! – Okay, I’m cheating here. Sorcery! is technically four books, but you really must do all of them or none of them. I’d push heavily for the former, as these advanced Fighting Fantasy books are right up there with Lone Wolf as some of the best the genre has to offer. Even if you’ve played inkle’s awesome take on the series, it’s worth looking into the originals. They’re different enough from each other that you’ll have a largely separate experience while still enjoying pointing at the things you recognize from the other version.

Steve Jackson’s Sorcery! – Okay, I’m cheating here. Sorcery! is technically four books, but you really must do all of them or none of them. I’d push heavily for the former, as these advanced Fighting Fantasy books are right up there with Lone Wolf as some of the best the genre has to offer. Even if you’ve played inkle’s awesome take on the series, it’s worth looking into the originals. They’re different enough from each other that you’ll have a largely separate experience while still enjoying pointing at the things you recognize from the other version.

The Way Of The Tiger: Avenger! – I like this one pretty much because it’s a ninja adventure in a fantasy land with a really involved combat system. Featuring surprisingly good writing, the only caveat I’ll throw out here is that the cliffhanger ending in the sixth book is absolutely infuriating. There’s a seventh book now that wraps things up, but if you do read through these, I’d like you to imagine waiting 25 years between the end of the sixth book and the start of the seventh. Anyway, Avenger! is where this series starts, and since they tell a linear story, it’s where you should start, too.

That’s all for part one of our on-going History Of Handheld RPGs feature. Please let me know what you think by commenting below, posting in the Official RPG Reload Club thread, or by tweeting me at @RPGReload. As for me, I’ll be back next week with a more typical installment of the Reload. We’ll be checking out Wizardry: Labyrinth Of Lost Souls (Free), and you just know that’s an excuse for me to go on about one of the great-grandparents of computer RPGs! Thanks as always for reading!

Next Week’s Reload: Wizardry: Labyrinth Of Lost Souls

Photographs of The Warlock Of Firetop Mountain, Sorcery!, and The Cave Of Time are courtesy of Neil Rennison of Tin Man Games.

Photographs of Avenger! and Lone Wolf: Flight From The Dark come from gamebooks.org, a fantastic resource for gamebooks of all types.