Hello, gentle readers, and welcome to the RPG Reload, the weekly feature where everything opens up once you have the compass. Each week, we take a look at an RPG from the past of the App Store to see how it’s doing in the here and now. It’s a little bit of revisiting, a little bit of reflecting, and a chance to take a deeper dive than our reviews typically allow for. I try to present a balanced plate of games from week to week, but if you feel like I’m missing anything important, please let me know. You can do that by commenting below, posing in the Official RPG Reload Club thread in the forums, or by tweeting me at @RPGReload. The schedule is already set for the next several months, so you might not see your suggestion soon, but it will be added to the master list.

Hello, gentle readers, and welcome to the RPG Reload, the weekly feature where everything opens up once you have the compass. Each week, we take a look at an RPG from the past of the App Store to see how it’s doing in the here and now. It’s a little bit of revisiting, a little bit of reflecting, and a chance to take a deeper dive than our reviews typically allow for. I try to present a balanced plate of games from week to week, but if you feel like I’m missing anything important, please let me know. You can do that by commenting below, posing in the Official RPG Reload Club thread in the forums, or by tweeting me at @RPGReload. The schedule is already set for the next several months, so you might not see your suggestion soon, but it will be added to the master list.

As an RPG fan, I love playing the big hits from familiar faces. There’s a consistency there that is almost comforting in its familiarity. Who doesn’t like the spectacle of a big-budget RPG flexing its visual and audio muscles? Seeing a massive world rendered in full 3D, where you can go anywhere and fall down endless rabbit holes of side-quests and silly things to try is incredible. I dare say that modern RPGs have some of the best production values and scope of any games out there. And yet, for many of us, that’s not how we came to the genre. Before the dramatic surge in presentation that the mid to late 1990s brought to the genre, RPGs weren’t generally considered lookers. Most of them were quite the opposite, relying on a great deal of abstraction and flavor text to ignite the player’s imagination. I can only speak for myself, but some of the worlds of those early RPGs are among the richest in my memories. As with the old debate of films versus books, there’s really no substitute for human imagination.

The massive rise of independent developers ushered in over the last 10 years or so has, generally by necessity, resulted in a lot more games that have to ask your imagination to fill in some of the blanks. Over on the PC platforms, where roguelikes have long found a market without much more than ASCII characters for graphics, the audience is at least somewhat receptive to such ideas. The mobile market, on the other hand, is a bit of an odd duck. It feels like going all out on visuals is a wasted effort, but shooting for anything under faux-retro “8-bit" graphics isn’t going to fly, either. The lack of a built-in hardware keyboard has made text-based games something of a non-starter as well. Somehow, amidst all of that, a strange little game called A Dark Room ($1.99) managed to make a pretty big splash a few years ago.

The massive rise of independent developers ushered in over the last 10 years or so has, generally by necessity, resulted in a lot more games that have to ask your imagination to fill in some of the blanks. Over on the PC platforms, where roguelikes have long found a market without much more than ASCII characters for graphics, the audience is at least somewhat receptive to such ideas. The mobile market, on the other hand, is a bit of an odd duck. It feels like going all out on visuals is a wasted effort, but shooting for anything under faux-retro “8-bit" graphics isn’t going to fly, either. The lack of a built-in hardware keyboard has made text-based games something of a non-starter as well. Somehow, amidst all of that, a strange little game called A Dark Room ($1.99) managed to make a pretty big splash a few years ago.

This RPG Reload is going to spoil A Dark Room almost in its entirely. It’s a game that is best enjoyed without knowing a single thing about it, so if you really want to get the maximum experience, stop reading and go get it now. You can come back after you’ve played it. I’ll still be here, I promise.

A Dark Room first released as a browser game in May of 2013. It was a product of Canadian game developer Michael Townsend, who hosts the game and a couple of other excellent creations on his site, Doublespeak Games. Townsend’s aim was to create something you could keep open during the day and peck away at in short bursts, discovering little pieces of the story organically as you played. According to an interview with The New Yorker, he chose this method of storytelling because, “it gives players the feeling that they are constructing the narrative, even if they’re only discovering it". The game ended up being quite popular, enough to catch the attention of American developer Amir Rajan, who had just left a software engineer job in Dallas and was looking for his next step.

A big believer in open-source, Townsend had already made the code freely available for people to examine and use. Rajan was interested in doing a port to iOS, as he thought the game would be a good fit for the platform. He got in touch with Townsend and got permission to port the game. Now, this is normally where I might recount the trials and tribulations of the game’s development, but Rajan himself documented things on his website far better than I ever could here. It’s rare to have such thorough notes from a development in progress made public, so I suggest reading them over. A Dark Room released on iPhone in November of 2013 and seemingly slipped right under the radar of most people, TouchArcade being no exception. After a few weeks, the game started getting some attention from various sources, including the TouchArcade forums, and sales picked up a little bit.

A big believer in open-source, Townsend had already made the code freely available for people to examine and use. Rajan was interested in doing a port to iOS, as he thought the game would be a good fit for the platform. He got in touch with Townsend and got permission to port the game. Now, this is normally where I might recount the trials and tribulations of the game’s development, but Rajan himself documented things on his website far better than I ever could here. It’s rare to have such thorough notes from a development in progress made public, so I suggest reading them over. A Dark Room released on iPhone in November of 2013 and seemingly slipped right under the radar of most people, TouchArcade being no exception. After a few weeks, the game started getting some attention from various sources, including the TouchArcade forums, and sales picked up a little bit.

Better times were ahead for A Dark Room, but before we get there, I want to talk about one of the noteworthy aspects of the game. Regular readers might recall a feature I wrote about visually-impaired iOS gamers. Not every game can be made to work for those players, but in my experience, they’re always searching for good candidates. That’s what happened in December of 2013, when a member of the AppleVis community reached out to Rajan to see about making the game accessible for the visually-impaired. Rajan promised on the spot to make the game fully-accessible, and that’s a promise he delivered on completely, not just for A Dark Room, but for his subsequent games as well.

Still, the game just sort of plucked along with daily sales in the double digits until one day in March of 2014, when Rajan awoke to see the game sitting at the #1 overall paid spot on the UK App Store. While it’s not entirely clear what caused it, something had finally sparked a fire for the game. Before long, it was having a similar level of success in several other App Store regions. It eventually cooled off, but even after it was out of the limelight, it was in far better shape than it had been in those early months. With Townsend’s blessing, Rajan got to work on a prequel of his own design called The Ensign ($1.99), and is currently in early development on a third game in the series.

A rare happy story for a paid RPG on the App Store, then. Looking at the game itself, if A Dark Room was going to have any serious success, it was going to have to go viral. A great deal of the game’s impact is in how it slowly peels back its layers to reveal a bigger world and story than you would ever initially expect. From the App Store description, screenshot, and even the first section of the game, it seems like little more than a cow-clicker, and a fairly low-rent one at that. In fact, if that’s all you’ve seen of the game, you’re probably wondering what it’s even doing in the RPG Reload. Well, you’ll have to trust me, friends.

A rare happy story for a paid RPG on the App Store, then. Looking at the game itself, if A Dark Room was going to have any serious success, it was going to have to go viral. A great deal of the game’s impact is in how it slowly peels back its layers to reveal a bigger world and story than you would ever initially expect. From the App Store description, screenshot, and even the first section of the game, it seems like little more than a cow-clicker, and a fairly low-rent one at that. In fact, if that’s all you’ve seen of the game, you’re probably wondering what it’s even doing in the RPG Reload. Well, you’ll have to trust me, friends.

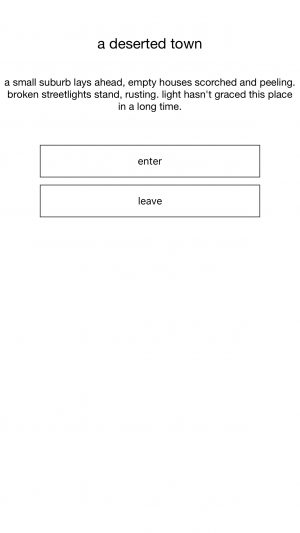

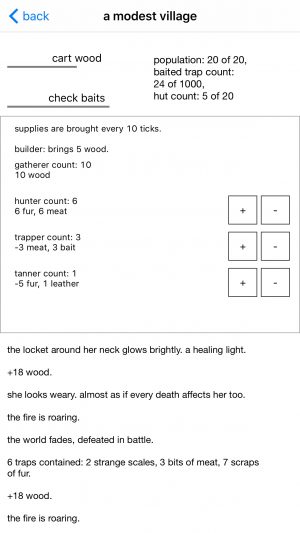

It all starts in that titular dark room, where your only option is to start a fire. You’ll need to tend that fire for a little while before someone arrives and offers to help. With their assistance, you can start collecting wood from the nearby forest. With that wood, you can build huts, which will attract new people to your little village. Then you can build some traps, which lets you gather fur, teeth, and pieces of cloth. Wait, do animals wear clothes? Hmm. As you keep on gathering supplies and increasing the size of your town, you get further options for buildings. Follow the trail, and a merchant will soon set up shop. For the most part, the merchant only sells things you’ve already discovered, allowing you to exchange surplus materials for others, but there is one curious object in his inventory: a compass.

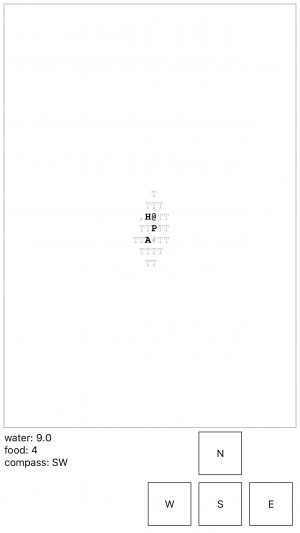

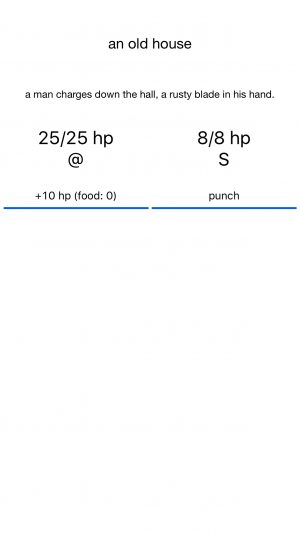

As you’re doing all of this, you’ll receive the occasional snippet of vague text. It’s hard to decipher most of it, but there are hints mixed in among the flavor text. You might also pick up on the changing tone of your growing settlement. Well, can’t be bothered with that. There’s progress to be made, after all. When you finally get enough resources together to trade for the compass, a new option is displayed. You can now embark on a journey down a dusty path. When you do, the whole nature of the game changes. You suddenly find yourself on an overworld map, albeit a crude one made up of ASCII letters and symbols. Although you can move freely in any direction, doing so consumes food and water, and chances are good that you didn’t bring much of either with you. The closest symbol is an ‘H’, representing a house, and if you move over to it, you have the option to explore inside of it.

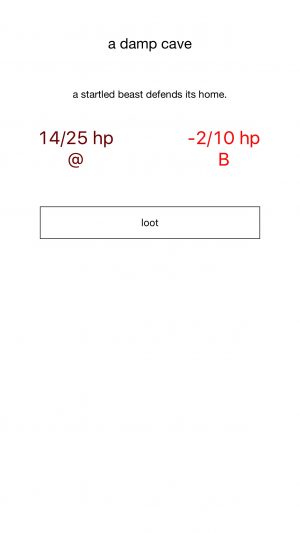

You’ll quickly find yourself in a semi-real time battle against another human. You have only your fists to defend yourself with, while he has a knife of some sort. He’s a bit ragged and low on health, however, while you are quite healthy, so it’s possible to outlast him. If you do, you can scavenge a variety of materials from his body and the rest of the house. After exploring the house, it becomes a safe point on the map where you can refill on food and water. You’ll also find caves on the map that require you to bring a torch to proceed. Animals wait inside, eager to defend their lairs. You’ll find some excellent materials deep in these caves, and just like the houses, they become safe points after you’ve cleared them out.

You’ll quickly find yourself in a semi-real time battle against another human. You have only your fists to defend yourself with, while he has a knife of some sort. He’s a bit ragged and low on health, however, while you are quite healthy, so it’s possible to outlast him. If you do, you can scavenge a variety of materials from his body and the rest of the house. After exploring the house, it becomes a safe point on the map where you can refill on food and water. You’ll also find caves on the map that require you to bring a torch to proceed. Animals wait inside, eager to defend their lairs. You’ll find some excellent materials deep in these caves, and just like the houses, they become safe points after you’ve cleared them out.

There are two ways back to town. You can return yourself, or you can die. If you die, you lose whatever you were carrying and won’t be able to head out again for a short period of time, but otherwise, the game will proceed just fine. If you’re able to make it back, you’ll drop any collected materials into storage and reap the rewards. New materials will increase the selection of goods in the local shops, allowing you to build new buildings, forge new equipment, and assemble more items. You’ll earn better equipment, and if you’re lucky, random encounters will give you new perks that improve your survivability. Each trip, you’re able to venture out farther and farther, but to what end?

Back home, things are taking on a decidedly more authoritarian tone. Your villagers are now referred to as slaves, and your character seems largely unconcerned with the well-being of any of them. Through their efforts and your expeditions, you’ll eventually come across abandoned towns with random stragglers, mines, and more. Then, the big discovery. A mysterious spaceship that sits in disrepair. It’s somehow familiar to your character, and you want to fix it. You can’t just use any material for it, however, so it’s off to search the ends of the map for what you need. Once you’ve fixed it to your satisfaction, A Dark Room has one last surprise for you.

Suddenly, you’ll find yourself dodging incoming objects in a twitch-based challenge. As you hurtle farther and farther into space, the objects come in greater numbers. If you’ve built your hull strong and dodge your share of the objects, you’ll eventually reach escape velocity, ending the game. Everything goes black, and you find yourself back at the start again. What does it all mean? If you piece the clues together, things start to make a bit of sense. At the very least, it seems like your character is an alien, and that you and your forces did a real number on this world. There is certainly room for other interpretations, however, and one of the cool things about A Dark Room is that it gives you enough hints to form a conclusion, but is vague enough to promote discussion about them. There’s also an alternate ending if you can avoid taking on any slaves. It takes a lot of patience, but it will give you more information about the game’s world if you can do it.

Suddenly, you’ll find yourself dodging incoming objects in a twitch-based challenge. As you hurtle farther and farther into space, the objects come in greater numbers. If you’ve built your hull strong and dodge your share of the objects, you’ll eventually reach escape velocity, ending the game. Everything goes black, and you find yourself back at the start again. What does it all mean? If you piece the clues together, things start to make a bit of sense. At the very least, it seems like your character is an alien, and that you and your forces did a real number on this world. There is certainly room for other interpretations, however, and one of the cool things about A Dark Room is that it gives you enough hints to form a conclusion, but is vague enough to promote discussion about them. There’s also an alternate ending if you can avoid taking on any slaves. It takes a lot of patience, but it will give you more information about the game’s world if you can do it.

This is all most effective the first time you play A Dark Room, when you have no expectations at all. But the game holds up surprisingly well on a replay, too. I find myself wishing I could speed certain jobs along at particular points earlier in the game, but even knowing what the future holds, there’s a certain enjoyment in building up your city and scouring the map for loot. I didn’t much enjoy the ship part this time around, but I didn’t care for it the first time either, so I guess that’s a wash. I think it’s impressive that the game holds up well even if you know its surprises ahead of time. I think the reason for that comes from the solid mechanics and vague story. The former keep you engaged, while the latter has you second-guessing any previous conclusions you might have made.

A Dark Room is a fun game with a lot of nostalgic charm for players familiar with the early RPG era, and its surprises are well-placed and effective. More than that, though, it’s an example of the power of imagination. With nothing more than text, symbols, and numbers, this game was able to captivate hundreds of thousands of people around the world, many of whom were likely born in a post-PlayStation world. It’s a wonderful example of how strong mechanics and carefully rationed-out story beats can carry a game without a fancy presentation. It’s also very well-suited to mobile. Rajan did a great job of redesigning the interface for touch screens, and he also added in a fair bit of story content that isn’t in the desktop version. I’d say that makes the mobile version of the game the ultimate version.

That’s what I think of A Dark Room, but what do you all think? I’d like to hear your thoughts, so please comment below the article, post in the Official RPG Reload Club thread, or tweet me at @RPGReload to let me know. This is also your last chance to get questions in for the next RPG Reload Podcast, so make sure to send those to [email protected]. We love hearing from you, friends! As for me, I’ll be back next week with the last part of our on-going History of Handheld RPGs series. Thanks for reading!

Next Week’s Reload: The History of Handheld RPGs, Part Twelve