Hello, gentle readers, and welcome to the RPG Reload. This week, we’re continuing our little monthly project looking at the history of handheld RPGs. That means that we will not be taking a look at a specific RPG from the App Store’s past this time around. Last month, we covered the beginnings of handheld electronic RPGs with a look at the Game Boy’s first several years. This month on, we’ll be exploring the rest of the Game Boy’s lifespan, including the event that brought the system back to life, and what came in its wake. In total, this feature will span twelve columns, each one taking a look at a specific era in handheld RPGs. I hope you enjoy reading them as much as I’ve enjoyed researching and writing them! Please let me know what you think by commenting below, posting in the Official RPG Reload Club thread, or by tweeting me at @RPGReload.

Hello, gentle readers, and welcome to the RPG Reload. This week, we’re continuing our little monthly project looking at the history of handheld RPGs. That means that we will not be taking a look at a specific RPG from the App Store’s past this time around. Last month, we covered the beginnings of handheld electronic RPGs with a look at the Game Boy’s first several years. This month on, we’ll be exploring the rest of the Game Boy’s lifespan, including the event that brought the system back to life, and what came in its wake. In total, this feature will span twelve columns, each one taking a look at a specific era in handheld RPGs. I hope you enjoy reading them as much as I’ve enjoyed researching and writing them! Please let me know what you think by commenting below, posting in the Official RPG Reload Club thread, or by tweeting me at @RPGReload.

It should go without saying that tabletop, computer, console, handheld, and mobile games are all inextricably tied with each other in various ways. To consider how other platforms contributed to handheld RPGs in these articles would grow them well beyond the scope I’m able to deal with. I’ll be mentioning some influences here and there, but this is basically a disclaimer that I’m aware handheld RPGs don’t exist in a vacuum, in spite of the relatively narrow historical focus of these articles.

The History Of Handheld RPGs, Part Three – Pokemania

The Game Boy wasn’t just winding down in 1995, it was nearly dead. It had fought a good fight, handily defeating all of its competitors and proving that handheld gaming had a place in the market just as much as console gaming did. Six years is a long time for any piece of gaming hardware, and even more so for the Game Boy, which was designed with the same philosophy as many Nintendo products. Using low-cost, older technology in a new and interesting way helped the Game Boy reach great success by making sure battery life was strong and the retail price was low. When it released in 1989, the games had looked a little antiquated next to 8-bit offerings, but many of the same gameplay experiences could be realized on the handheld, so it wasn’t a big issue. When the 16-bit consoles arrived, it felt a little older, but still not dramatically behind the curve.

In Japan, both the SEGA Saturn and Sony PlayStation launched in late 1994, with US releases following the next year. Nintendo would arrive late to the party in 1996, but make no mistake, the 3D era had arrived. With so many new platforms to try their luck at, third parties had little interest in spending resources on Game Boy projects beyond a whole lot of licensed mediocrity, and even Nintendo had their teams spread pretty thin. The Super Nintendo needed software to help it survive until its successor was ready. Said successor, the Nintendo 64, also needed software to help sell it in a heavily-competitive market. The Virtual Boy had come and gone in 1995 with a lifespan of about a half year, and while it didn’t get a ton of support from Nintendo, what little it did get likely came at the expense of new Game Boy titles.

While I doubt Nintendo expected the Virtual Boy to be a smashing success, its swift failure left Nintendo in a position where they needed to keep the Game Boy afloat until the Nintendo 64 was released and plans for a handheld successor could be put together. There were lots of rumors at the time about a 32-bit handheld code-named Project Atlantis that was supposed to be released in 1997, so I’d assume Nintendo was looking to tread water until then. So, as they often do in a system’s twilight years, Nintendo largely looked to its external partners. Hudson provided a Bomberman/Wario cross-over game, Atari provided ports of some of its arcade classics, Bullet-Proof Software had a new Tetris variation, Rare had a couple of ports of their SNES games, Intelligent Systems and HAL Laboratory offered up a few titles, and so on. It’s doubtful that Nintendo planned to make a lot of money on any of these games, but rather wanted to keep retail shelves stocked and Game Boy’s name in front of people’s eyes.

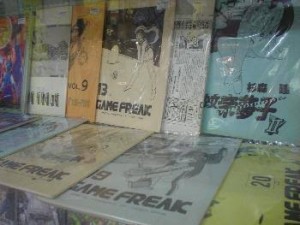

One of the developers whose game was picked up by Nintendo in this period was on-again, off-again collaborator Game Freak. Although the majority of their work had been for Nintendo platforms, the small private company’s origins go back even farther than Nintendo’s entry into the hardware business. The founder of the company, Satoshi Tajiri, was in some ways like any Japanese teenager in the late 1970s. That is to say, he was obsessed with Taito’s Space Invaders, and spent a lot of his free time and money playing the game, trying to improve his skills and get better scores. He became so good at the game, people were frequently looking to him for advice and tips. Sensing an opportunity, he produced a few pages of advice, made a bunch of photocopies, and sold them to people at the local arcade. It was a big success. Before the average kid finished high school, Tajiri was already making a good salary with his business venture, now a full-fledged fanzine called Game Freak.

One of the developers whose game was picked up by Nintendo in this period was on-again, off-again collaborator Game Freak. Although the majority of their work had been for Nintendo platforms, the small private company’s origins go back even farther than Nintendo’s entry into the hardware business. The founder of the company, Satoshi Tajiri, was in some ways like any Japanese teenager in the late 1970s. That is to say, he was obsessed with Taito’s Space Invaders, and spent a lot of his free time and money playing the game, trying to improve his skills and get better scores. He became so good at the game, people were frequently looking to him for advice and tips. Sensing an opportunity, he produced a few pages of advice, made a bunch of photocopies, and sold them to people at the local arcade. It was a big success. Before the average kid finished high school, Tajiri was already making a good salary with his business venture, now a full-fledged fanzine called Game Freak.

As the 1980s wore on, Tajiri had become less than impressed with the way the game market was going. He felt there were too many bad games, and not enough of the good, interesting ones. It’s a sentiment just about every gamer feels at certain points in the hobby, but unlike most of us, Tajiri decided to do something about it. He and his associates, including among others Game Freak’s in-house artist Ken Sugimori, opted to pitch a game to Namco. They came up with an action-puzzle concept called Quinty, and Namco agreed to publish it for the 8-bit Nintendo console. Released in Japan in 1989, a US release under the title Mendel Palace followed the next year, and suddenly, Game Freak was in the software business. Amazingly, their next title would be for Nintendo, a puzzle game titled Yoshi’s Egg in Japan, with titled simply Yoshi in America. This time, Game Freak would develop the game for two platforms, the NES and Nintendo’s new handheld, the Game Boy. Although it was critically panned, Yoshi was a reasonable sales success, giving Game Freak the capital to spread their wings a little. In the next few years, Game Freak would develop titles for almost every major platform, working with companies like SEGA, Sony, and Victor Interactive. Nintendo would again allow them the use of their flagship character in 1993 for a quirky Japan-only SNES puzzle game called Mario & Wario.

Of course, all of these were just side projects for Satoshi Tajiri. His ultimate idea came near the start of Game Freak’s game development days, and its inspirations far earlier than that, even. In his youth, before video games came along, the object of Tajiri’s obsession was collecting insects. The area just outside of Tokyo where Tajiri grew up was mostly countryside in his childhood days, and the young boy enjoyed finding new insects and examining their behaviors. He often took them home, at least until he noticed that some of them would kill and eat others when kept in the same location. Besides searching the tall grass, Tajiri was also fond of catching beetles by leaving a rock near the base of a tree, reasoning that beetles seeking a cool place to sleep during the day would crawl under it. He was correct. As he grew up and the countryside gave way to pachinko parlors and office buildings, Tajiri lamented that the new generation of kids wouldn’t have the same chance he did to indulge in exploring nature. I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention that Tajiri was also a big fan of Ultra Seven, a Japanese superhero who battled enemies using monsters he sprung from capsules. That’s probably pretty relevant.

Of course, all of these were just side projects for Satoshi Tajiri. His ultimate idea came near the start of Game Freak’s game development days, and its inspirations far earlier than that, even. In his youth, before video games came along, the object of Tajiri’s obsession was collecting insects. The area just outside of Tokyo where Tajiri grew up was mostly countryside in his childhood days, and the young boy enjoyed finding new insects and examining their behaviors. He often took them home, at least until he noticed that some of them would kill and eat others when kept in the same location. Besides searching the tall grass, Tajiri was also fond of catching beetles by leaving a rock near the base of a tree, reasoning that beetles seeking a cool place to sleep during the day would crawl under it. He was correct. As he grew up and the countryside gave way to pachinko parlors and office buildings, Tajiri lamented that the new generation of kids wouldn’t have the same chance he did to indulge in exploring nature. I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention that Tajiri was also a big fan of Ultra Seven, a Japanese superhero who battled enemies using monsters he sprung from capsules. That’s probably pretty relevant.

There were two things about the Game Boy that caused these ideas to coalesce on that platform as opposed to any other. Before the advent of wi-fi communication, portable game hardware had to communicate the old-fashioned way: with a cable. When Tajiri first saw the link cable, he imagined creatures traveling along the wire from one player’s game to another. There’s one final piece we need to get to Pokemon‘s basic form, however, and that comes from none other than Akitoshi Kawazu of Squaresoft. Specifically, his Game Boy game, The Final Fantasy Legend, which was the first handheld electronic RPG. Tajiri played the game and thought the gameplay of an RPG suited the platform well. Even with all of these elements brought together, however, Satoshi Tajiri had trouble selling Nintendo on the idea, and nothing may have ever come of it were it not for Gary “Effing" Oak.

Gary Oak, Pokemon protagonist Ash Ketchum’s obnoxious rival, has a different name in Japan. While Ash is known as Satoshi in his homeland, Gary Oak’s original name is Shigeru. These names aren’t mere chance. Satoshi is indeed named after Satoshi Tajiri, while Shigeru is named for none other than Nintendo’s star designer and Mario creator, Shigeru Miyamoto. Even though Nintendo couldn’t quite visualize Tajiri’s concept, Miyamoto was interested enough in the basic idea to want to work with him and explore it out further. Miyamoto worked directly with Tajiri, acting as a sort of mentor. Even with his help, development was slow. The project was started soon after the Game Boy’s Japanese launch, but wouldn’t see release until 1996. Game Freak’s other projects were keeping its employees paid, albeit just barely, with Tajiri himself drawing no salary. In the end, Nintendo second-party Creatures, Inc. had to provide some capital to keep the developer above water, receiving an equal share in the rights to the beleaguered project. With the help of Nintendo and Miyamoto, the game was finally finished, albeit in an incredibly buggy form, in early 1996. Coming into a relatively dead market on the Game Boy platform, it’s hard to say what everyone’s expectations were, but they probably weren’t all that hopeful.

Gary Oak, Pokemon protagonist Ash Ketchum’s obnoxious rival, has a different name in Japan. While Ash is known as Satoshi in his homeland, Gary Oak’s original name is Shigeru. These names aren’t mere chance. Satoshi is indeed named after Satoshi Tajiri, while Shigeru is named for none other than Nintendo’s star designer and Mario creator, Shigeru Miyamoto. Even though Nintendo couldn’t quite visualize Tajiri’s concept, Miyamoto was interested enough in the basic idea to want to work with him and explore it out further. Miyamoto worked directly with Tajiri, acting as a sort of mentor. Even with his help, development was slow. The project was started soon after the Game Boy’s Japanese launch, but wouldn’t see release until 1996. Game Freak’s other projects were keeping its employees paid, albeit just barely, with Tajiri himself drawing no salary. In the end, Nintendo second-party Creatures, Inc. had to provide some capital to keep the developer above water, receiving an equal share in the rights to the beleaguered project. With the help of Nintendo and Miyamoto, the game was finally finished, albeit in an incredibly buggy form, in early 1996. Coming into a relatively dead market on the Game Boy platform, it’s hard to say what everyone’s expectations were, but they probably weren’t all that hopeful.

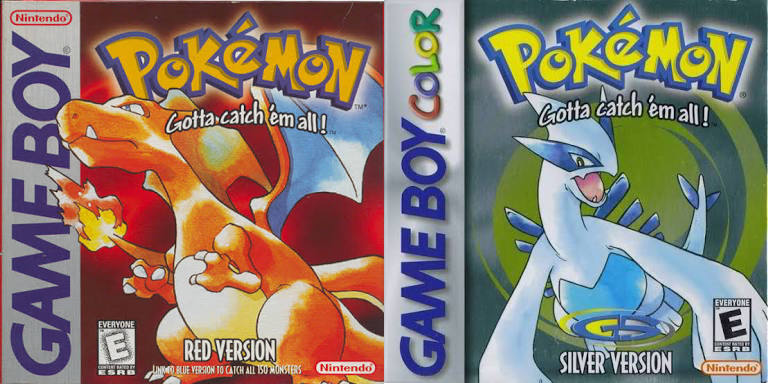

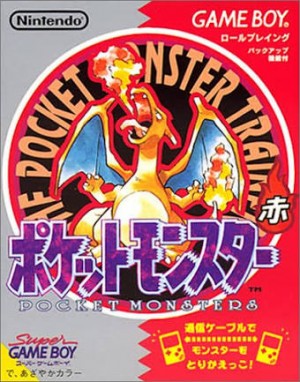

Under the advisement of Shigeru Miyamoto, Pocket Monster released in two different versions, each containing a different distribution of the game’s 151 monsters. Players who wanted to collect every monster would have to trade with another player, promoting the game’s social elements. Pocket Monster Red and Pocket Monster Green released in Japan in February of 1996, and it didn’t take long for it to catch on with kids. Later in the year, a new, less buggy version of the game with new artwork was released as a special mail order offer to subscribers of popular children’s comic magazine CoroCoro Comic. Called Pocket Monster Blue, it would serve as the basis for the worldwide release of the game in 1998 and 1999 as Pokemon Red and Blue (the Pokemon name was used instead of Pocket Monsters to avoid legal issues). An anime series came in 1997 which still runs to this day, itself spawning 18 full-length movies and counting. Pokemon even successfully managed to put collectible card games in the hands of average kids, bolstering a market which had leaned solely on Magic: The Gathering up to that point. In spite of the success of the media empire that is Pokemon, however, everything comes back around to the games, which occupy slots one through ten of the top-selling RPGs of all-time worldwide to date.

Under the advisement of Shigeru Miyamoto, Pocket Monster released in two different versions, each containing a different distribution of the game’s 151 monsters. Players who wanted to collect every monster would have to trade with another player, promoting the game’s social elements. Pocket Monster Red and Pocket Monster Green released in Japan in February of 1996, and it didn’t take long for it to catch on with kids. Later in the year, a new, less buggy version of the game with new artwork was released as a special mail order offer to subscribers of popular children’s comic magazine CoroCoro Comic. Called Pocket Monster Blue, it would serve as the basis for the worldwide release of the game in 1998 and 1999 as Pokemon Red and Blue (the Pokemon name was used instead of Pocket Monsters to avoid legal issues). An anime series came in 1997 which still runs to this day, itself spawning 18 full-length movies and counting. Pokemon even successfully managed to put collectible card games in the hands of average kids, bolstering a market which had leaned solely on Magic: The Gathering up to that point. In spite of the success of the media empire that is Pokemon, however, everything comes back around to the games, which occupy slots one through ten of the top-selling RPGs of all-time worldwide to date.

Pokemon wasn’t the first RPG with a monster-catching mechanic, of course. Megami Tensei predates it many years, and though Dragon Quest 5 entered production years after Pokemon did, it still beat the game to the market with its monster-catching gameplay. Why did Pokemon‘s brand of monster-battling catch fire in a way the systems in those games didn’t? There are probably many factors at play, not the least of which being the broad appeal of the Pokemon monster designs, which run the spectrum from cute to cool. If you ask me, it’s right in the franchise’s English slogan. “Gotta Catch ‘Em All", it commands, and kids are more than happy to oblige. Previous RPGs with a monster-catching mechanic not only didn’t encourage collecting every monster, they flat out didn’t allow it. Particularly with the success of trading cards and collectible stickers in the 1980s, it’s a wonder nobody hit on the idea properly before Pokemon did. Tajiri was also correct about the link cable. Multiplayer was baked into Pokemon from the very start, allowing not only competition but cooperation between players. Also, I doff my hat to Miyamoto for the two-version thing, because you know a lot of people bought both.

The massive success of Pokemon revived the Game Boy in Japan, and to the Japanese game industry’s credit, nobody slept on either point. While it would take Nintendo a little while to bring out an official sequel, they sated interest in the meantime with the 1998 release of one more version of the original game, Pocket Monster Pikachu, which drew in aspects from the anime series right down to a Pikachu that wouldn’t stay in its Pokeball. On the hardware side, Nintendo decided to delay their 32-bit handheld for a while and instead introduced the Game Boy Color worldwide in late 1998. This launch came just after the North American release of the original Pokemon games, proving to be a killer combo for Christmas that year. The European release the following year met with a similarly warm reception. Though people were calling it a fad from the very start, Pokemon had managed to find major success worldwide, something very few other games ever did.

The massive success of Pokemon revived the Game Boy in Japan, and to the Japanese game industry’s credit, nobody slept on either point. While it would take Nintendo a little while to bring out an official sequel, they sated interest in the meantime with the 1998 release of one more version of the original game, Pocket Monster Pikachu, which drew in aspects from the anime series right down to a Pikachu that wouldn’t stay in its Pokeball. On the hardware side, Nintendo decided to delay their 32-bit handheld for a while and instead introduced the Game Boy Color worldwide in late 1998. This launch came just after the North American release of the original Pokemon games, proving to be a killer combo for Christmas that year. The European release the following year met with a similarly warm reception. Though people were calling it a fad from the very start, Pokemon had managed to find major success worldwide, something very few other games ever did.

Third parties started coming back to the Game Boy, many with their own variations on Nintendo and Game Freak’s breakout hit. Enix finally brought their main franchise to Nintendo’s handheld with Dragon Warrior Monsters in 1998, a game that wasn’t even slightly subtle about its reasons for existing. Hudson spun the wheel twice in 1998, once with Bomberman Quest and again with the more on-the-nose Robopon, which came in Sun, Star, and Moon versions. In 1999, Konami got in on the craze with a demon-collecting variation on their popular Goemon/Mystical Ninja series, while Capcom made a robot-themed attempt with Metal Walker. A few RPGs that had no inspiration from Pokemon arrived that year, too. Atlus followed up Last Bible with a sequel, Nintendo presented an odd RPG/golf hybrid in Mario Golf, and Konami released the clever Survival Kids. Enix put forth strong proof of their new commitment to Nintendo handhelds with a port of the Super Famicom Dragon Quest 1 & 2 remake collection.

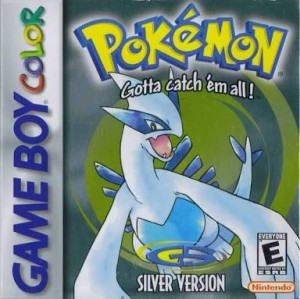

While the rest of the world would have to wait until the following year, late 1999 also saw the release of Pokemon‘s official sequels: Pokemon Gold and Pokemon Silver. Interestingly, when the game originally entered production, it was intended to be the final Pokemon game. All of the rest of the merchandising had simply been intended as promotion for these games, even the trading card game. As such, the developers tried to throw everything they could into the games, resulting in it being delayed from its originally-intended late 1998 release date. The games featured a real-time clock which had certain Pokemon only appearing at certain times, a Pokemon breeding system, rare Shiny Pokemon, and the ability for Pokemon to hold certain items to use in battle. Critically, the game featured backwards compatibility with the previous titles. Pokemon could be traded from the older games to the newer one, and to facilitate this movement, the ability to delete moves was added to the game. All of this came in addition to more expected fare like a new world to explore, new Pokemon to catch, and two new elemental types to add further complexity to battles.

It felt like a massive improvement over the original games, with so much more content that the first game felt minuscule in comparison. Almost as a way of emphasizing that point, players who battled through the Elite Four and became the Pokemon Champion in the game were treated to a jaw-dropping revelation. After the credits rolled, your character is given a special boat ticket that leads to the region that the first game took place in. It’s a bit scaled back, but there are eight more badges to collect, and it all culminates with an epic battle against – who else – the hero of the first game. It’s an unfathomably awesome way to end the game, and it only happened because of the work of Mr. Satoru Iwata, the former president of Nintendo who passed away earlier this year. At the time, Iwata was the guy they called in when things had gone wrong, and the Pokemon sequel certainly qualified. Game Freak and Creatures, Inc had already filled the game cartridge with the new Johto region, but with a little programming optimization from Satoru Iwata, there was enough room left in memory for that epic return to the original game’s region.

It felt like a massive improvement over the original games, with so much more content that the first game felt minuscule in comparison. Almost as a way of emphasizing that point, players who battled through the Elite Four and became the Pokemon Champion in the game were treated to a jaw-dropping revelation. After the credits rolled, your character is given a special boat ticket that leads to the region that the first game took place in. It’s a bit scaled back, but there are eight more badges to collect, and it all culminates with an epic battle against – who else – the hero of the first game. It’s an unfathomably awesome way to end the game, and it only happened because of the work of Mr. Satoru Iwata, the former president of Nintendo who passed away earlier this year. At the time, Iwata was the guy they called in when things had gone wrong, and the Pokemon sequel certainly qualified. Game Freak and Creatures, Inc had already filled the game cartridge with the new Johto region, but with a little programming optimization from Satoru Iwata, there was enough room left in memory for that epic return to the original game’s region.

With the Pokemon sequel bolstering it, the Game Boy Color ended up getting a couple more years of life. The year 2000 was a particularly strong year for RPGs on the platform. A nice mix of Pokemon-inspired releases and more traditional fare made for a pleasing balance. Representing the Pokemon clones, we had the Puyo Puyo spin-off Arle’s Adventure: The Magic Jewel from Compile, a younger-skewing Megami Tensei game called Devil Children from Atlus, and original efforts Keitai Denju Telefang and Lil’ Monster. Ports and spin-offs were also pretty popular, with Dragon Quest 3, Crystalis, Heroes Of Might & Magic, Warriors Of Might & Magic, Quest: Brian’s Journey, Azure Dreams, and Grandia: Parallel Trippers all showing up on one side of the ocean or the other. Nintendo and Camelot followed up the unusual Mario Golf with the equally odd RPG/tennis mash-up Mario Tennis. Card games were also coming into vogue, no small thanks due to Pokemon‘s popular take on the genre. Not only did Game Boy see a video game version of the Pokemon Trading Card Game, it also played host to Monster Rancher Battlecard and Intelligent Systems’ Trade & Battle: Card Hero. Sadly, many of these games never left Japan, but enough did to keep RPG fans happy when they were away from their brand-new PlayStation 2 machines.

With the Pokemon sequel bolstering it, the Game Boy Color ended up getting a couple more years of life. The year 2000 was a particularly strong year for RPGs on the platform. A nice mix of Pokemon-inspired releases and more traditional fare made for a pleasing balance. Representing the Pokemon clones, we had the Puyo Puyo spin-off Arle’s Adventure: The Magic Jewel from Compile, a younger-skewing Megami Tensei game called Devil Children from Atlus, and original efforts Keitai Denju Telefang and Lil’ Monster. Ports and spin-offs were also pretty popular, with Dragon Quest 3, Crystalis, Heroes Of Might & Magic, Warriors Of Might & Magic, Quest: Brian’s Journey, Azure Dreams, and Grandia: Parallel Trippers all showing up on one side of the ocean or the other. Nintendo and Camelot followed up the unusual Mario Golf with the equally odd RPG/tennis mash-up Mario Tennis. Card games were also coming into vogue, no small thanks due to Pokemon‘s popular take on the genre. Not only did Game Boy see a video game version of the Pokemon Trading Card Game, it also played host to Monster Rancher Battlecard and Intelligent Systems’ Trade & Battle: Card Hero. Sadly, many of these games never left Japan, but enough did to keep RPG fans happy when they were away from their brand-new PlayStation 2 machines.

That sort of puts it into perspective, doesn’t it? When Game Boy launched, the 8-bit Nintendo console was still at the top of the pile. When Game Boy was finally replaced by the long-delayed Game Boy Advance in 2001, console players were playing the demo for Metal Gear Solid 2 and looking forward to Final Fantasy 10. The wildest part of it is that Game Boy probably could have kept going even longer, judging by the packed release lists. The card game boom that hit around the turn of the millennium was an easy enough concept to portray on the simple Game Boy hardware, and we’ll see a lot of that as we go into 2001, the last big year for Game Boy RPGs. By this time, things were starting to wrap up, but some big titles were still in the pipeline.

Dragon Quest Monsters 2 hit, this time with two different versions available. This was one of the last Pokemon clones on the Game Boy, with the tide moving strongly towards card games instead. In terms of more traditional RPGs, Japanese players got Star Ocean: Blue Sphere and ports of the original Wizardry trilogy, while both sides of the ocean were treated to Lufia: The Legend Returns. Pokemon Crystal released in the first half of the year, serving a similar role to Gold & Silver as Pokemon Pikachu did for Red & Blue. Japanese gamers got a sequel to the Pokemon Trading Card Game and a Shin Megami Tensei Trading Card game, while American gamers got Magi Nation and a Harry Potter And The Sorcerer’s Stone RPG. The last two RPGs for the Game Boy released in 2002. One was a card game based on Dragon Ball Z, while the other was Harry Potter And The Chamber Of Secrets.

Dragon Quest Monsters 2 hit, this time with two different versions available. This was one of the last Pokemon clones on the Game Boy, with the tide moving strongly towards card games instead. In terms of more traditional RPGs, Japanese players got Star Ocean: Blue Sphere and ports of the original Wizardry trilogy, while both sides of the ocean were treated to Lufia: The Legend Returns. Pokemon Crystal released in the first half of the year, serving a similar role to Gold & Silver as Pokemon Pikachu did for Red & Blue. Japanese gamers got a sequel to the Pokemon Trading Card Game and a Shin Megami Tensei Trading Card game, while American gamers got Magi Nation and a Harry Potter And The Sorcerer’s Stone RPG. The last two RPGs for the Game Boy released in 2002. One was a card game based on Dragon Ball Z, while the other was Harry Potter And The Chamber Of Secrets.

With that, the Game Boy finally passed its baton on to the next generation. While it would be a much shorter-lived generation than the previous one, it would be an exciting one for RPG fans. And Pokemania lived on, as it continues to do to this very day. We’ll catch up with Game Boy’s successor in a little while, but first, we’re going to take a look at the brave souls that met their makers at the pointy end of the Game Boy’s creamed-spinach display over the course of more than a decade. Yes, they’ll all fit in one article.

Shaun’s Five For The Game Boy Pokemania Era

For each part of this series, I’ll be selecting five notable or interesting titles to highlight. If you’re looking to get a good cross-section of the era in question, these picks are a good place to start.

Pokemon Red/Blue/Yellow – With Pokemon being as iterative as it is, unless you’re into spelunking history, you’re probably better off playing a newer Pokemon title or even the Game Boy Advance remakes of these games. That said, that quality also makes it a little easier to go back to the originals than with certain other series. Pokemon has come a long way in many ways, but in others, it hasn’t changed much at all. It’s worth checking out just on its historical merits, I think, and it’s still just about as good as it ever was.

Pokemon Gold/Silver/Crystal – This game had perhaps the easiest job of any RPG sequel. All it had to do was deliver another helping of the same to a very hungry fanbase. With that in mind, it’s surprising just how much this follow-up improved on its predecessor. This ended up being one of the bigger jumps the series has seen so far, and it’s often pointed to as the best game in the series by many. I don’t know if I’d go that far, but it’s perhaps one of the few times a Pokemon mainline sequel truly felt fresh. The game’s numerous improvements were useful and clear enough for even non-hardcore fans to take note of, and the post-game return to the Kanto region from the first game was one of the most memorable secrets of its day.

Dragon Warrior Monsters – Much as I love the series, Dragon Quest has never been shy about latching onto the soup du jour to keep the franchise relevant. In 2016, that means the Minecraft-inspired Dragon Quest Builders, but in 1998, it meant doing a take-off of Nintendo’s latest hit. The series is still going today, with the latest release being a 3DS remake of the second Dragon Quest Monsters game. To be honest, although the Dragon Quest set dressing goes far with me, the games aren’t nearly as high-quality as the Pokemon titles in any way save perhaps presentation. They’re decent enough that any Dragon Quest fan should have a good time plumbing them for fanservice, however, and a good alternative if you’re burnt out on Pokemon‘s formula.

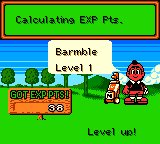

Mario Golf – While technically not the first golfing game from Nintendo starring Mario, this was, along with its Nintendo 64 sister title, the first Mario Golf game developed by Camelot Software Planning, the developers behind SEGA’s Shining Force series. While the N64 game is a pretty straightforward game of golf, Camelot couldn’t resist dipping their RPG chocolate specialty into the Game Boy Color game’s golfing peanut butter. Rather than play as any of the famous Nintendo characters, you play as a generic upstart golfer just starting out at the Marion Country Club. By playing tournaments and completing challenges, you’ll level up and be able to improve your stats as you see fit. Sports games have always had a little RPG in them, but this one lays it all out on the table.

Dragon Warrior 3 – Yes, this is available on iOS, and it’s a perfectly good version of the game. While the Game Boy Color version lags behind significantly in most aspects of its presentation, it’s a superior version in at least a few ways. There’s more content than the mobile version, and the animated monsters really help bring battles to life. That said, even this venerated title can’t escape Pokemon‘s influence completely. The Monster Medals were a hateful little addition to the game that nevertheless kept players coming back to grind, grind, and grind some more in hopes of each and every monster dropping their precious medal. Gotta catch ’em all?

That’s all for part three of our on-going History Of Handheld RPGs feature. Please let me know what you think by commenting below, posting in the Official RPG Reload Club thread, or by tweeting me at @RPGReload. As for me, I’ll be back next week with a look at Valorware’s 9th Dawn ($2.99)! Thanks as always for reading!

Next Week’s Reload: 9th Dawn