I can’t tell you what your experience of Benjamin Rivers’ Home ($2.99) will be like. Not really. It’s not exactly a matter of player choice, either. We might both pick up the same gun, visit the same rooms, tap the same spots, but in the end we will discover that our experiences were not the same. Our choices were not just concrete— they are subjective.

I can’t tell you what your experience of Benjamin Rivers’ Home ($2.99) will be like. Not really. It’s not exactly a matter of player choice, either. We might both pick up the same gun, visit the same rooms, tap the same spots, but in the end we will discover that our experiences were not the same. Our choices were not just concrete— they are subjective.

Home is a horror adventure, an exploration of an uneasy world. It can be scary—one moment sent a very literal chill down my spine—but for the most part it doesn’t ply that sort of fear. It reaches for something deeper, for a creeping awareness of a wrongness that doesn’t improve as you find more answers, that doesn’t dissipate in some violent climax.

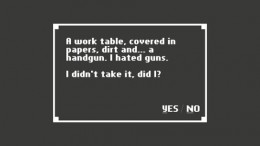

Like any point-and-click adventure, you travel, explore, and collect things. Or perhaps you don’t. Each time your hero comes to a point where a decision must be made, he asks you: did I do it? Did I pick up that gun? Did I make that choice? You say yes, or you say no—he tells you how the result of that decision made him feel. You and he must create the narrative mutually.

Whether you collect things or not, you pick up information. Wanted or not, things slip in. Whether you demand to know the answers or would rather continue in ignorant bliss, the information becomes hard to ignore. The story comes together. That creeping sense of wrongness expands, points at dreadful possibilities, and ultimately leaves you to decide for yourself: did you see what you think you saw? Or is the answer more complex?

Home doesn’t trade in unrelenting ambiguity, though. It is simply subjective. What you know, what you learn, builds the story for you. The things you learn and encounter create the context of your playthrough. I did not manage to find the “right" answer to all my questions—I don’t know that one exists. Since subjectivity is woven through all the threads of Home, I rather hope it doesn’t.

Home doesn’t trade in unrelenting ambiguity, though. It is simply subjective. What you know, what you learn, builds the story for you. The things you learn and encounter create the context of your playthrough. I did not manage to find the “right" answer to all my questions—I don’t know that one exists. Since subjectivity is woven through all the threads of Home, I rather hope it doesn’t.

Aside from answering yes or no in each pivotal moment, all there is to do in Home is point and tap, look and listen. The game recommends you play in darkness, with headphones. It helps. Fear is more convincing in the dark, and Home is more valuable when it’s allowed to be frightening.

At times, small flaws get in the way. Tap targets can be overly finicky. The text is slow-moving and impatient tapping will ensure you miss things. Particular sequences of actions lead to inescapable crashes. It holds up well against last year’s desktop release, but it’s not without its problems.

The biggest problem Home faces, however, is that it’s design begs players to try again, to run through a second time, a third. But each repetition takes away from the magic. It’s fascinating to play close attention and see how your possibilities expand and contract based on the choices you make; less so to walk the same paths, poke the same objects and jump to the same scares. Your conclusions about it may look nothing like mine, but the concrete parts get familiar fast.

Home is a good game: thought-provoking, unsettling, and original. Perhaps it is better as a conversation, though. It has something to say about reality, about perception, and about how we react to our fears. Digested alone, its observations may be limited. Shared between us, it has quite a lot to say.