Hello, gentle readers, and welcome to the RPG Reload, the regular feature where all good things must come to an end. To be specific, welcome to the RPG Reload Glossary, where we sift through the piles of historical debris and messy semantics to try to make some sense of it all. This time around, we’re finishing our look at the history of the JRPG sub-genre. In the last part, we looked at a decade which could charitably be referred to as a hangover from the massive success of the genre in the 1990s. Square, the biggest name in JRPGs, over-extended itself in spectacular fashion and ended up merging with their rival, Enix. The Japanese market lost its taste for home consoles, focusing instead on the convenience that handheld consoles brought to the table. Development on two of the three most popular JRPG series had slowed down considerably, and as the first decade of the new millennium came to a close, you didn’t have to look far to find people proclaiming the death of the JRPG genre had come.

Hello, gentle readers, and welcome to the RPG Reload, the regular feature where all good things must come to an end. To be specific, welcome to the RPG Reload Glossary, where we sift through the piles of historical debris and messy semantics to try to make some sense of it all. This time around, we’re finishing our look at the history of the JRPG sub-genre. In the last part, we looked at a decade which could charitably be referred to as a hangover from the massive success of the genre in the 1990s. Square, the biggest name in JRPGs, over-extended itself in spectacular fashion and ended up merging with their rival, Enix. The Japanese market lost its taste for home consoles, focusing instead on the convenience that handheld consoles brought to the table. Development on two of the three most popular JRPG series had slowed down considerably, and as the first decade of the new millennium came to a close, you didn’t have to look far to find people proclaiming the death of the JRPG genre had come.

As in most cases of such proclamations, there was quite a bit of exaggeration going on. Still, it’s safe to say that the JRPG genre as it was traditionally known went through a pretty rough patch for several years. A lot of that was tied in with the many problems Square Enix was having. One of the reasons why I’ve put such a heavy focus on the two-giants-that-became-one is that for a very long time, Square, Enix, and their associated IPs might as well have been the JRPG genre as far as public perception was concerned. It’s no surprise that the frequency of articles lamenting the passing of JRPGs seems to increase hand-in-hand with the number of public problems Square is having at any given time. Final Fantasy was in a bad way from almost every angle in the late 00s, and for many people, that meant JRPGs were, too.

But the problems were bigger than that, of course. I’m going to take a stab at explaining things as best as I can. First, we have to consider that when it comes to JRPGs, the Japanese market and the Western market might as well be two different planets. The genre had some struggles in both markets, but those issues were quite different in severity and nature. With most JRPG-style games originating in Japan (obviously), the genre’s health is more strongly tied with that market, but it’s impossible to deny the importance of the overseas market, particularly post-Final Fantasy 7. On a basic level, both markets became challenging due to increased competition from related genres and some of the major players in the JRPG genre fumbling.

As mentioned, home consoles were on the wane in Japan. That’s not to say that they weren’t still selling decent numbers even in decline, but after the releases of the Nintendo DS and Sony PlayStation Portable, it wasn’t hard to see the differences in the size of each hardware platform’s audience. The advent of HD consoles dramatically increased the budget of home console development, the PC gaming market was practically non-existent, and Japanese customers just weren’t that thrilled with any of it. Depending on how much of your potential market was in Japan versus the rest of the world, it would probably make a lot of sense to put your game on handhelds. They had a larger, more diverse audience, and the budgets for games were quite reasonable. Dragon Quest‘s main audience is in Japan, so it was easy enough to move the series to Japan’s console of choice, the Nintendo DS. Final Fantasy, on the other hand, depended on Western support, so such a move wasn’t really feasible.

In Japan, JRPGs had always had fairly wide appeal across a variety of demographics. The explosion in popularity of Capcom’s Monster Hunter series with 2008’s Monster Hunter Portable 2nd G on the PlayStation Portable lured a large portion of the lucrative teen and young adult audience away from the traditional JRPG genre. The wide adoption of smartphones as the decade came to a close was initially seen as a boon to the genre, given that JRPGs can adapt to touch controls better than many traditional genres. And for a while, it was. Then, in 2012, a new kind of RPG became popular with the release of Gungho’s Puzzle & Dragons on mobile phones. JRPGs had barely gotten used to being second fiddle, and now they were demoted down to third. Pretty much everyone with a smart device was now playing these new social RPGs.

What did this leave for the JRPG? Well, there were still quite a few dedicated fans of the genre who still showed their support. Enough to fuel smaller companies that played to their preferred niches, anyway. But the biggest remaining audience for the genre ended up being elementary school kids, surprisingly enough. Proportionately few of them owned smart devices, at least at that time, and the nature of the genre had always been a good fit for those with developing (or declining) motor skills. Pokemon remained the game of choice for this crowd, of course, but another franchise managed to reap the rewards as well.

You might recall Level-5 as the co-developer of Dragon Quest 8 for the PlayStation 2. They also co-developed Dragon Quest 9. But they were increasingly becoming a company looking to invest in its own properties rather than contracting out to others. They did so with a canny (some would say cynical) eye towards promising potential markets. Their biggest success on the Nintendo DS was the Professor Layton series of puzzle games, but they had found a solid back-up in their soccer RPG series Inazuma Eleven. It’s hard to go wrong with sports anime and manga in Japan, and the extreme popularity of Captain Tsubasa decades earlier paved the way nicely for soccer stories in particular to find an audience.

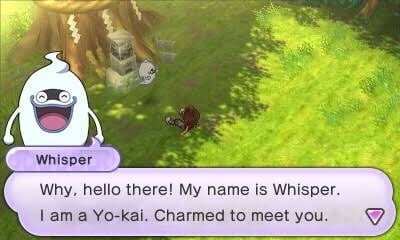

When the Nintendo 3DS launched, Level-5 put out some entries in their previously reliable franchises and found people weren’t quite biting in the same way. Fortunately, Level-5 was a big fan of the classic method of throwing mud against the wall and seeing what stuck, and the next sticky clump would become an out-and-out phenomenon in Japan for a few years. In 2013, Level-5 released Yo-Kai Watch for the Nintendo 3DS. It hits a lot of the same appeal points as Pokemon, but with more of an emphasis on Japanese folklore. The games are even more accessible than Pokemon, if you can believe it. Like most of Level-5’s attempts to appeal to kids, Yo-Kai Watch came with a TV show, toy line, and everything else you can imagine. Japanese kids bit hard, and for a few years, Yo-Kai Watch was everywhere in Japan. In the moment, it seemed like the first credible threat to Pokemon‘s crown, though time has proven that it lacked Pokemon‘s stamina.

For JRPG lovers in a slightly older age bracket, their needs were largely served by companies like Atlus, Namco, Falcom, and Idea Factory. Atlus had always been that weird kid that was a little too interested in the occult, but the successful re-styling of Persona 3 and Persona 4 demonstrated the value of appealing to a more mainstream anime crowd. They were still making games on a ridiculously low budget, but the resulting efforts were selling beyond their usual demographic. Even Western gamers were starting to pick up on the company’s efforts thanks to Persona. The company knew that Persona 5 presented a great chance for Atlus to break into the mainstream, and they got to work on it after doing a successful console test run with the puzzle game Catherine.

For their part, Namco more or less kept right on doing what it always had been. The Tales series of JRPGs had always had a relatively consistent audience, loyal enough to buy new hardware when it was necessary. The general style of the games meant that more powerful hardware didn’t necessarily require an exponential increase in development resources the way that Final Fantasy‘s more realistic style did. In the years-long absence of new single-player Final Fantasy and Dragon Quest entries, Tales quietly became one of the meat-and-potatoes dishes of JRPG fans around the world.

Another beneficiary of that absence was Falcom, whose Trails series of JRPGs nicely scratched the itch many players had for big, woolly stories in the classic style. Trails became Falcom’s most popular franchise by a good stretch, easily out-pacing Ys. Unfortunately, the series wouldn’t catch on much at all outside of Japan until its PC version got an eventual English release on Steam and GOG. But the Japanese sales were more than enough to keep a relatively small company like Falcom healthy.

Finally, there’s Idea Factory. The company may not get a lot of respect from the masses, but they saw the rise of a trend and have done an amazing job of serving it for a long time now. A couple of parts before this one, I talked about how Evangelion heralded a rise in nihilistic and/or deconstructive media in Japan. Well, like all phases, that eventually burnt out. You can only be down for so long, after all. The next big trend was not entirely an unfamiliar one, but it’s rarely been so concentrated. Moe anime, a style that focuses on cute, lovable girls and their typically light-hearted adventures, became the dominant form of media in Japan in the new millennium. The audience for such shows and comic books was a diverse one (as with any sufficiently mainstream success), but it included at its core a particularly valuable sub-group of young adults that loved to splurge on merchandise.

Idea Factory and developer Compile Heart aimed directly at that burgeoning market. They had largely been known for making overly-complicated and somewhat mediocre TRPGs with the occasional JRPG release, but they had their fans. Their Agarest War series had been reasonably successful, but not so successful that they felt shackled to it. One of their releases between Agarest games was a moe-styled parody of the game industry called Hyperdimension Neptunia, which imagined the console wars as a battle between goddesses, each representing a hardware platform. It was a great concept, and the industry is certainly ripe for parody. The game itself was… well, it wasn’t outside of their usual quality. It was acceptable enough that a lot of people who bought the game for its clever concept were willing to give the developer another shot. Which is just what they did, turning Neptunia into a little cottage industry. Fans of the company are quite loyal, so even Compile Heart’s games released between Neptunia releases fare well enough at this point.

So it went for the JRPG business in Japan. The gaps left by the struggling major players were filled in by smaller, more agile publishers. The ones I’ve mentioned are some of the bigger ones, but there were many others as well. It was hardly the salad days of old, but provided you didn’t mind the step down in production values, it wasn’t hard to find a good JRPG to play at any given point. If anything, the lack of sizzle meant that developers had to work even harder to come up with unique systems and settings. When combined with the lower budgets that handheld projects carried with them, some genuinely unusual JRPGs were released during this period.

Over in the West, a different yet similar problem was occurring. For the first few console generations, most of the greatest RPG publishers in the West stuck to home computers. Microsoft’s entry into the console market, the Xbox, started to change that. Notably, they managed to lure both Bioware and Bethesda, two of the bigger CRPG developers, into releasing RPGs for their platform. They both apparently liked what they tasted, and when the next generation of consoles brought even more computing power with it, they and others from the PC scene were there with bells on. Between these tested developers and stunning new faces like CD Projekt and their Witcher series, RPG fans in the Western market suddenly had a surplus of great choices without even needing to glance at Japan’s output. Indeed, since many console players had only dabbled in PC gaming, these games also enjoyed the benefit of feeling fresh and unusual when compared to previous console RPGs.

Due to a variety of social and cultural circumstances, handhelds weren’t nearly as popular with young adults in the West as they were in Japan. The Nintendo DS sold to a lot of older players, but few of them were interested in RPGs. With severe competition on the home consoles, a general lack of a presence on PC, and the shape of the age demographics gaming on handhelds, the primary market for JRPGs in the West was… elementary school children. Funny how that worked out. And of course, also as in Japan, there was a reasonably good-sized group of hardcore genre fans who were sufficient to support carefully-budgeted efforts. The gaps were again filled mostly with mid-level Japanese publishers, though Square still tossed out the occasional high-quality effort like Bravely Default on the Nintendo 3DS.

When Final Fantasy 13 failed to ignite the console JRPG market, it seemed to deflate hopes that things would ever get turned around on the PlayStation 3 and Xbox 360. Nevertheless, there were some console successes. Level-5’s Ni no Kuni put to rest the notion that it was too difficult to create huge open worlds in an HD JRPG. Star Ocean developer Tri-ace put out a handful of games, and a couple of them even sold reasonably well. Namco’s Tales games were solid performers worldwide, too. JRPGs were no longer the “it" genre on consoles in any region, but there were still games to be had if you looked carefully enough. Most of the action was on handhelds for several years, though.

It took the success of the PlayStation 4 to really wake things up on the console front. Japanese developers seemed invigorated by the new platform, and it certainly didn’t hurt that Western-style RPGs no longer had the “new puppy" feel for console gamers that they enjoyed in the previous generation. Square Enix seemed to start getting a handle on their issues, and even nailed down a date for the beleaguered Final Fantasy 15, which had first been announced alongside Final Fantasy 13 as Final Fantasy Versus 13. Persona 5 was nearly a victim of some unrelated nonsense with Atlus’s parent company at the time, but it too got on track. It also seemed as though the latest Dragon Quest was on the horizon, this time splitting the difference and releasing both a handheld and a console version.

As for all of the mid-level developers and publishers who had held up the previous generation, they also stuck around. At the same time, the Nintendo 3DS started to wind down, and with no one at the time quite sure of how Nintendo’s next platform would fare, there was really nowhere to go but to the wild west of mobile or the safe confines of the PlayStation 4. Most chose the latter, as social RPGs were (and are) still eating almost all of the RPG lunch on mobile platforms. The success of a few test cases on Steam encouraged many Japanese publishers to give the Windows platform a go for the first time, too. If you were the sort of player who didn’t touch handhelds, the last few years probably looked like a humongous renaissance for the JRPG genre. In some respects, it certainly was.

It’s interesting to note the direction these new console JRPGs are taking, though. Lessons were clearly learned from the previous generation, as having large open worlds, action-based combat, and lots of extra add-on content and post-release expansions seemed to become a priority. In the classical sense of the genre, is Final Fantasy 15 even a JRPG? Is Nier Automata? How about Dark Souls? And what of games like Cosmic Star Heroine that are made in the West but in the distinct JRPG style? Trying to answer these questions will only ruin polite dinner conversation, so I don’t recommend thinking too hard about it all.

I suppose this is as good a place as any to put a pin in this tale. This history wasn’t as thorough as I would have liked it to be, but I think it would take a book to do the topic with full justice, and we have already been pushing it here already. We won’t be revisiting this topic here on TouchArcade, but I may get back around to it again on my own personal blog, Post Game Content. If you like my history articles and retrospectives, you should probably keep an eye on that site. As for me, I’ll be back next week with the very last Reload column. Yep.

Next Week’s Reload: The 2017 Golden Pancho Awards

We pride ourselves on delivering quality, long-form articles like this one instead of the SEO-driven click bait that is slowly taking over the internet. Unfortunately, articles like these rarely generate the traffic (and as a result, the ad revenue) of listicles, cheat guides, and other junk.

Please help us continue producing content like this by supporting TouchArcade on Patreon, doing your Amazon shopping by first visiting toucharcade.com/amazon, and/or making one-time contributions via PayPal.