Hello, gentle readers, and welcome to the RPG Reload, the regular feature where we always bring a party. To be specific, welcome to the RPG Reload Glossary, where we sift through the piles of historical debris and messy semantics to try to make some sense of it all. This time around, we’re continuing our look at the history of the JRPG sub-genre. In the last part, we went through the origins of this popular sub-genre through the 1980s. By the close of the decade, JRPGs were by far the most popular kinds of games in Japan, but had yet to make much of a dent in other regions. The 1990s would change all of that, and it largely came down to two games in particular. The lead-up to that ultimate breakthrough held plenty of great games, many of which were deliberate attempts to appeal to the Western market.

Hello, gentle readers, and welcome to the RPG Reload, the regular feature where we always bring a party. To be specific, welcome to the RPG Reload Glossary, where we sift through the piles of historical debris and messy semantics to try to make some sense of it all. This time around, we’re continuing our look at the history of the JRPG sub-genre. In the last part, we went through the origins of this popular sub-genre through the 1980s. By the close of the decade, JRPGs were by far the most popular kinds of games in Japan, but had yet to make much of a dent in other regions. The 1990s would change all of that, and it largely came down to two games in particular. The lead-up to that ultimate breakthrough held plenty of great games, many of which were deliberate attempts to appeal to the Western market.

To repeat the note from last time: due to the immense size of this particular sub-category, I’m going to be focusing on only the titles that were critical to the development and/or popularization of the genre. This is a necessary move to keep this particular historical retelling from growing to an absurd size.

There are a few major events we’ll want to look at in this critical decade for the genre. As already mentioned, this is the decade when the genre finally broke out worldwide. It was through that worldwide success that the previous genre king, Dragon Quest, was finally bested in sales. The significant advances in hardware technology allowed JRPGs to become more cinematic than ever, a change that altered perceptions of the genre and what the average person tended to look for in it. This was, without question, the decade of Square, a publisher that had barely survived the 1980s. By the end of the 1990s, they had soared to tremendous heights, inching ever closer to the sun that would eventually melt their wings. Given the importance of this decade, I’ve decided to split it into two parts. This week, we’ll cover the first half, when Nintendo’s Super NES ruled the JRPG roost thanks to being the exclusive host of the two biggest publishers in the genre.

Let’s start from the beginning of the decade, however. After a long two years, Enix was finally ready to release the next game in their mega-hit Dragon Quest franchise. Dragon Quest 4 put a greater emphasis on story-telling and characterization than the previous games. It also introduced a somewhat controversial AI system for controlling party members. In completely breaking ties with the world and history of the previous three games, Dragon Quest 4 had to carve its own way. It also had to do that on a game console that was clearly on its way out. The game was nevertheless a huge success, albeit less so than its predecessor. If nothing else, it cemented Dragon Quest‘s reputation as the top of the JRPG heap.

Let’s start from the beginning of the decade, however. After a long two years, Enix was finally ready to release the next game in their mega-hit Dragon Quest franchise. Dragon Quest 4 put a greater emphasis on story-telling and characterization than the previous games. It also introduced a somewhat controversial AI system for controlling party members. In completely breaking ties with the world and history of the previous three games, Dragon Quest 4 had to carve its own way. It also had to do that on a game console that was clearly on its way out. The game was nevertheless a huge success, albeit less so than its predecessor. If nothing else, it cemented Dragon Quest‘s reputation as the top of the JRPG heap.

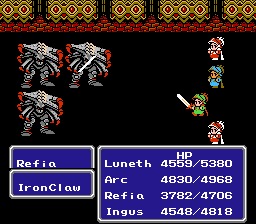

Square, on the other hand, made a nice recovery from the mixed reception of Final Fantasy 2. Just a couple of months after the release of Dragon Quest 4, Final Fantasy 3 released on the 8-bit Nintendo platform. This game married the story-telling emphasis of the second game to the more comfortable mechanics of the first. It also was the first implementation of Final Fantasy‘s now-famous job system. This was almost certainly a reaction to a similar system being included in Dragon Quest 3, but Square made their take a much bigger part of the game, incorporating its presence into the main story. Their efforts were rewarded with a huge jump in sales, nearly doubling up on Final Fantasy 2 en route to becoming Square’s first million-seller. That good news was slightly offset by the limited success of the first Final Fantasy game in America, which was published in mid-1990 by Nintendo.

Although Dragon Quest still enjoyed a strong lead over Final Fantasy, Square was moving in on the JRPG genre with everything they could muster. They had already beaten Enix to the punch on Game Boy with SaGa/Final Fantasy Legend in 1989, and would follow that game up with two more sequels in the following two years. But Nintendo had yet another new platform debuting in 1990, and Square meant to stake a claim as soon as possible there, too. Thus, barely a year after the release of the third Final Fantasy, Square launched Final Fantasy 4 for Nintendo’s 16-bit Super Famicom in July of 1991. The sales didn’t improve much from the previous game in the series, but the improved production values helped Square’s team tell a more immersive story. There would be no going back to generic characters for the series now. With this release, there were now an equal amount of Final Fantasy and Dragon Quest games. Final Fantasy would never look back.

Although Dragon Quest still enjoyed a strong lead over Final Fantasy, Square was moving in on the JRPG genre with everything they could muster. They had already beaten Enix to the punch on Game Boy with SaGa/Final Fantasy Legend in 1989, and would follow that game up with two more sequels in the following two years. But Nintendo had yet another new platform debuting in 1990, and Square meant to stake a claim as soon as possible there, too. Thus, barely a year after the release of the third Final Fantasy, Square launched Final Fantasy 4 for Nintendo’s 16-bit Super Famicom in July of 1991. The sales didn’t improve much from the previous game in the series, but the improved production values helped Square’s team tell a more immersive story. There would be no going back to generic characters for the series now. With this release, there were now an equal amount of Final Fantasy and Dragon Quest games. Final Fantasy would never look back.

As if to emphasize that point, 1992 saw the release of two new Final Fantasy games. The first, Final Fantasy: Mystic Quest, was initially released in the United States. This was a very rudimentary take on the JRPG concept that was deliberately designed to teach Westerners how to play a JRPG. It’s a little insulting in hindsight, and perhaps even more so given that the other Final Fantasy release for the year was Final Fantasy 5. That one would remain a Japanese exclusive for a number of years due to concerns that it was too complicated for the relatively inexperienced players of the West. It’s a great game, with a much better version of the job system seen in Final Fantasy 3 and more emotive character sprites than those found in the previous installment. It smashed the sales of Final Fantasy 4, selling well over 2 million copies and putting the series within sniffing distance of Dragon Quest for the first time.

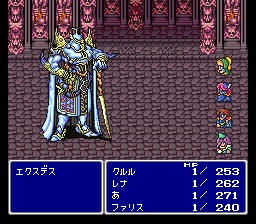

Speaking of, Dragon Quest finally made its 16-bit debut in the fall of 1992 with Dragon Quest 5. Its unique narrative, following the story of a hero from childhood all the way through his adult years, marriage, and eventual fatherhood, was one of the best the sub-genre had ever seen. Still, it couldn’t quite measure up to the competition’s visual flourish, leaving some feeling like the game was a bit old-fashioned. This was also the first Dragon Quest game to not receive an English localization. Indeed, Enix would take a costly break from Western publishing over the next several years, a move that likely contributed to Dragon Quest‘s low popularity outside of Japan. In Japan, Dragon Quest 5 sold 2.8 million copies. That’s a great number by any measure, but it was lower than the previous two games and disturbingly near to its closest rival.

Speaking of, Dragon Quest finally made its 16-bit debut in the fall of 1992 with Dragon Quest 5. Its unique narrative, following the story of a hero from childhood all the way through his adult years, marriage, and eventual fatherhood, was one of the best the sub-genre had ever seen. Still, it couldn’t quite measure up to the competition’s visual flourish, leaving some feeling like the game was a bit old-fashioned. This was also the first Dragon Quest game to not receive an English localization. Indeed, Enix would take a costly break from Western publishing over the next several years, a move that likely contributed to Dragon Quest‘s low popularity outside of Japan. In Japan, Dragon Quest 5 sold 2.8 million copies. That’s a great number by any measure, but it was lower than the previous two games and disturbingly near to its closest rival.

It should be noted that in Japan, the Super NES was already swimming in JRPGs by this point. Square and Enix had both released a number of games outside of their main franchises, and just about every publisher was either releasing or preparing their own entries. The most important one to note for 1992 is probably Atlus’s Shin Megami Tensei, a sort-of reboot of the series they had previously worked on for Namco. The brand would yield considerable success for Atlus in the future, with the Persona spin-offs doing particularly well. Lunar: The Silver Star, from publisher Game Arts, also made its debut in this year, providing an oasis for thirsty SEGA CD owners.

1993 was the first year in some time that didn’t have a new release from one of the two big JRPG brands. Just about everyone else showed up, however. Capcom had Breath of Fire, Taito had Lufia, SEGA had Phantasy Star 4, Tecmo had Secret of the Stars, and so on. I’ll leave it up to you which of these are worth remembering, but none of them really had any major impact on the genre itself. Breath of Fire at least did well enough to earn a handful of sequels, partly on the back of being moderately successful outside Japan.

By 1994, the 16-bit console generation was hitting its last big stride. At least in Japan, new consoles would arrive by the end of year, with international releases not far behind them. In spite of that, this was a fantastic year for 16-bit JRPGs. Nintendo’s Earthbound thumbed its nose at the conventions of the genre while telling a deeply human story in a bizarrely distorted version of reality. Lunar: Eternal Blue served as the ultimate funeral dirge for the SEGA-CD, while Capcom and Atlus both followed up their recent successes with Breath of Fire 2 and Shin Megami Tensei 2 respectively. Atlus would also release a spin-off of Shin Megami Tensei named Shin Megami Tensei If…, which is generally seen as the spiritual ancestor of Persona.

By 1994, the 16-bit console generation was hitting its last big stride. At least in Japan, new consoles would arrive by the end of year, with international releases not far behind them. In spite of that, this was a fantastic year for 16-bit JRPGs. Nintendo’s Earthbound thumbed its nose at the conventions of the genre while telling a deeply human story in a bizarrely distorted version of reality. Lunar: Eternal Blue served as the ultimate funeral dirge for the SEGA-CD, while Capcom and Atlus both followed up their recent successes with Breath of Fire 2 and Shin Megami Tensei 2 respectively. Atlus would also release a spin-off of Shin Megami Tensei named Shin Megami Tensei If…, which is generally seen as the spiritual ancestor of Persona.

The big gun, however, belonged to Square. Final Fantasy 6 arrived in the Spring of 1994, and it more or less established the future course of the series. Focusing heavily on character drama and impressive set pieces, the sixth game in the series also served as something of a changing of the guard. The first main characters designed by soon-to-be lead artist Tetsuya Nomura appear in this game, and this is also the directing debut of Yoshinori Kitase, who would be heavily involved in the franchise from here on out. In spite of the heavy praise the game received, it ultimately only sold a little more than Final Fantasy 5 had. Hardly peanuts, mind you.

Dragon Quest would take another year to catch up, with Dragon Quest 6 arriving in 1995 after a fairly lengthy development period. The main things to note here include the return of the job class system in a new form, and the heavy focus on vignettes involving NPCs as opposed to only following the main party. While Dragon Quest 5 had been criticized for looking out of date, Dragon Quest 6 looked fantastic. Sales were up on the previous game, and the gap between Dragon Quest and Final Fantasy was once again quite wide. However, like the fifth game, Dragon Quest 6 only released in Japan. North American sales for Final Fantasy games weren’t huge by any means, but it certainly made for a closer race overall.

Dragon Quest would take another year to catch up, with Dragon Quest 6 arriving in 1995 after a fairly lengthy development period. The main things to note here include the return of the job class system in a new form, and the heavy focus on vignettes involving NPCs as opposed to only following the main party. While Dragon Quest 5 had been criticized for looking out of date, Dragon Quest 6 looked fantastic. Sales were up on the previous game, and the gap between Dragon Quest and Final Fantasy was once again quite wide. However, like the fifth game, Dragon Quest 6 only released in Japan. North American sales for Final Fantasy games weren’t huge by any means, but it certainly made for a closer race overall.

Funnily enough, Dragon Quest 6 ended up having to compete with another game from its own creator. Square had managed to get Yuji Horii, Dragon Quest‘s creator, and Akira Toriyama, Dragon Quest‘s artist, to join up with Final Fantasy‘s creator Hironobu Sakaguchi on a “Dream Team" RPG. Chrono Trigger blasted out of the gates in the first half of 1995, bridging the gap between teen manga and video games more than just about any game ever had. Its contributions to the genre are many, including New Game+, having battles take place on the exploration screen without any cut-aways, and more. The game sold like wild in Japan, and even did reasonably well in North America.

The new 32-bit consoles were still picking up steam, but a few JRPGs managed to trickle out. The most notable of the lot in 1995 is probably Konami’s PlayStation RPG Suikoden. Though its sequel would end up being even more significant, the original game was quite impressive for its time in some ways. Over on the Saturn, Atlus released another Shin Megami Tensei spin-off named Devil Summoner. It was relatively slim pickings as far as quality efforts went, but both systems would eventually see their fair share of successes in the JRPG genre.

As the last fumes of the 16-bit generation burned out in 1996, Nintendo and Square worked together to try yet again to appeal to the Western audience. Super Mario RPG: Legend of the Seven Stars fused action elements with a turn-based combat system to create something that felt both true to Square’s style of RPG and the Mario franchise itself. While it did quite well, Square and Nintendo would soon part ways rather bitterly. Many of the original development team members from Square eventually split off from the company to found Alpha Dream, the developer behind all of the Mario & Luigi RPGs. The action commands used in its battle system would find their way into many later JRPGs.

This is probably as good a place as any to stick a pin in this. The second half of 1996 would see the debut release of the most popular JRPG series in history, and one of the key games that would finally achieve the goal of cracking open the Western market. The other piece of the puzzle wouldn’t be far behind it. We’ll take a look at that in the next part of this series, which will be coming up next week. As always, thanks for reading!

Next Week’s Reload: The Continuing History of JRPGs