Hello, gentle readers, and welcome to the RPG Reload, the regular feature where we sometimes hold down the confirm button because we are lazy. To be specific, welcome to the RPG Reload Glossary, where we get all up in fussy semantics, history, and other things that polite society will shun us for. Having covered social RPGs, tactical RPGs, and action RPGs in previous installments, we now turn our attention to another one of the big dogs of the RPG category: the JRPG. As messy as trying to define action RPGs was, JRPGs are in some way even more difficult to nail down. As with the last couple of Glossary features, you can expect this one to span multiple columns, with roughly one for each decade. In today’s installment, we’ll be looking at the origins and early years of the genre, loosely covering the 1980s.

Hello, gentle readers, and welcome to the RPG Reload, the regular feature where we sometimes hold down the confirm button because we are lazy. To be specific, welcome to the RPG Reload Glossary, where we get all up in fussy semantics, history, and other things that polite society will shun us for. Having covered social RPGs, tactical RPGs, and action RPGs in previous installments, we now turn our attention to another one of the big dogs of the RPG category: the JRPG. As messy as trying to define action RPGs was, JRPGs are in some way even more difficult to nail down. As with the last couple of Glossary features, you can expect this one to span multiple columns, with roughly one for each decade. In today’s installment, we’ll be looking at the origins and early years of the genre, loosely covering the 1980s.

One note before we get started: due to the immense size of this particular sub-category, I’m going to be focusing on only the titles that were critical to the development and/or popularization of the genre. This will make it a little different from the previous Glossary features, but it’s necessary to avoid going to book-length.

Breaking from the norm, I am not going to include a list of features that define the genre. This genre is simply too wide and messy to even begin doing that. In lieu of a list, let me simply state that my image of JRPGs is the genre that crystallized in the wake of Dragon Quest and its immediate progeny. Note that I’m going with ‘JRPG’ as in ‘the genre of games’ rather than ‘JRPG’ as in ‘RPGs which were made in Japan’. While the latter can be a useful label in certain discussions, it doesn’t quite fit what I’ve been going for with these Glossary articles.

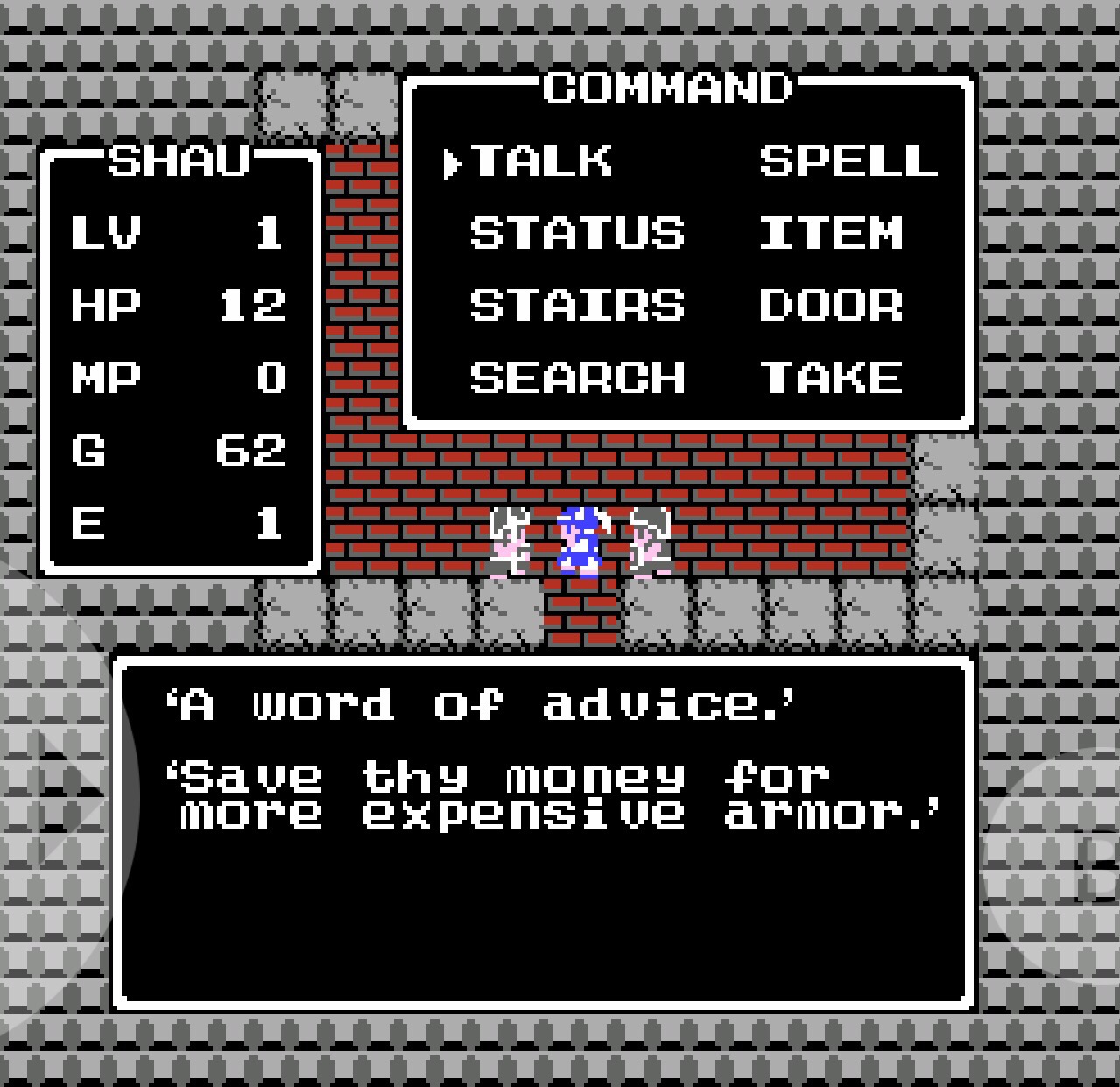

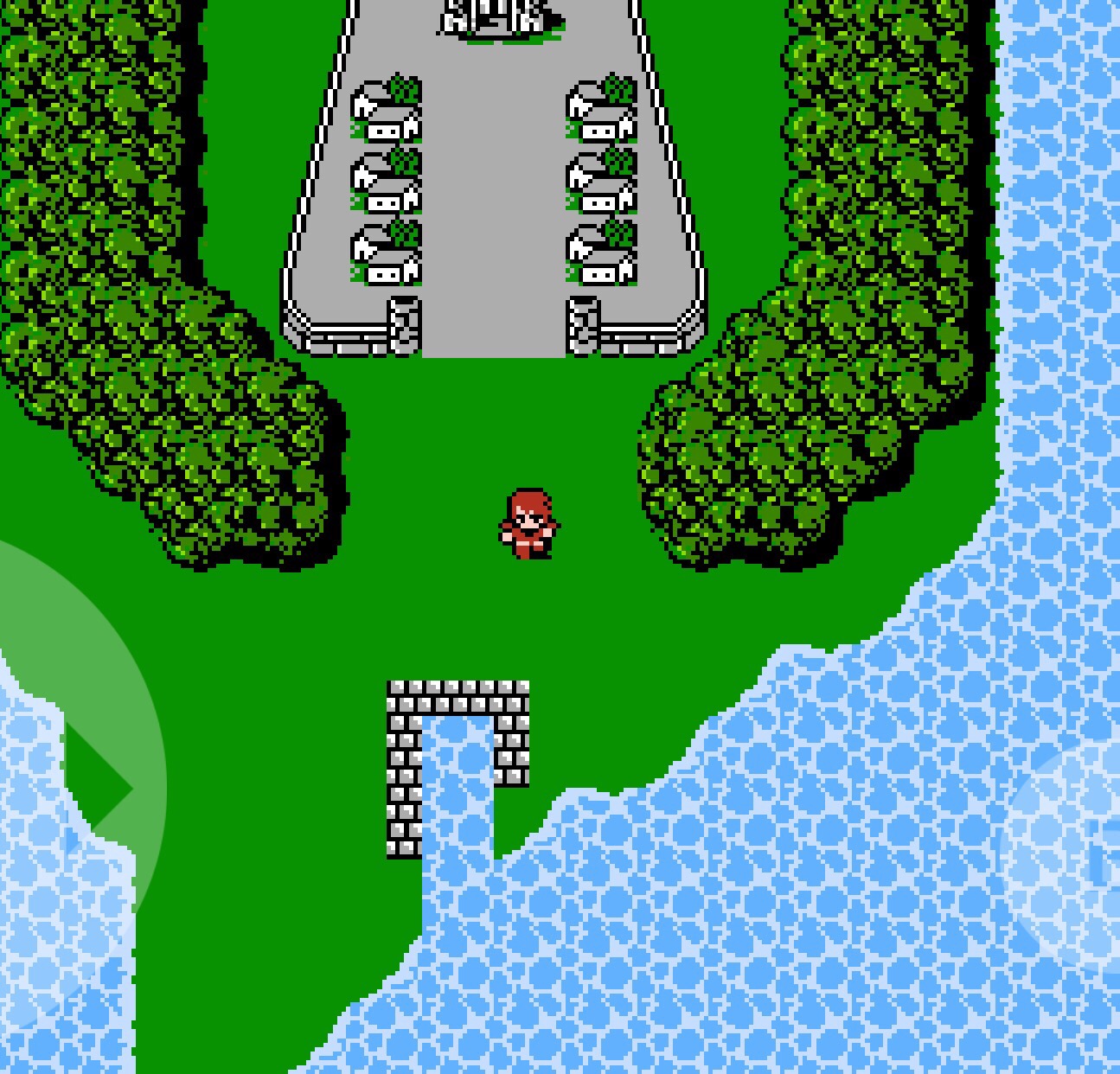

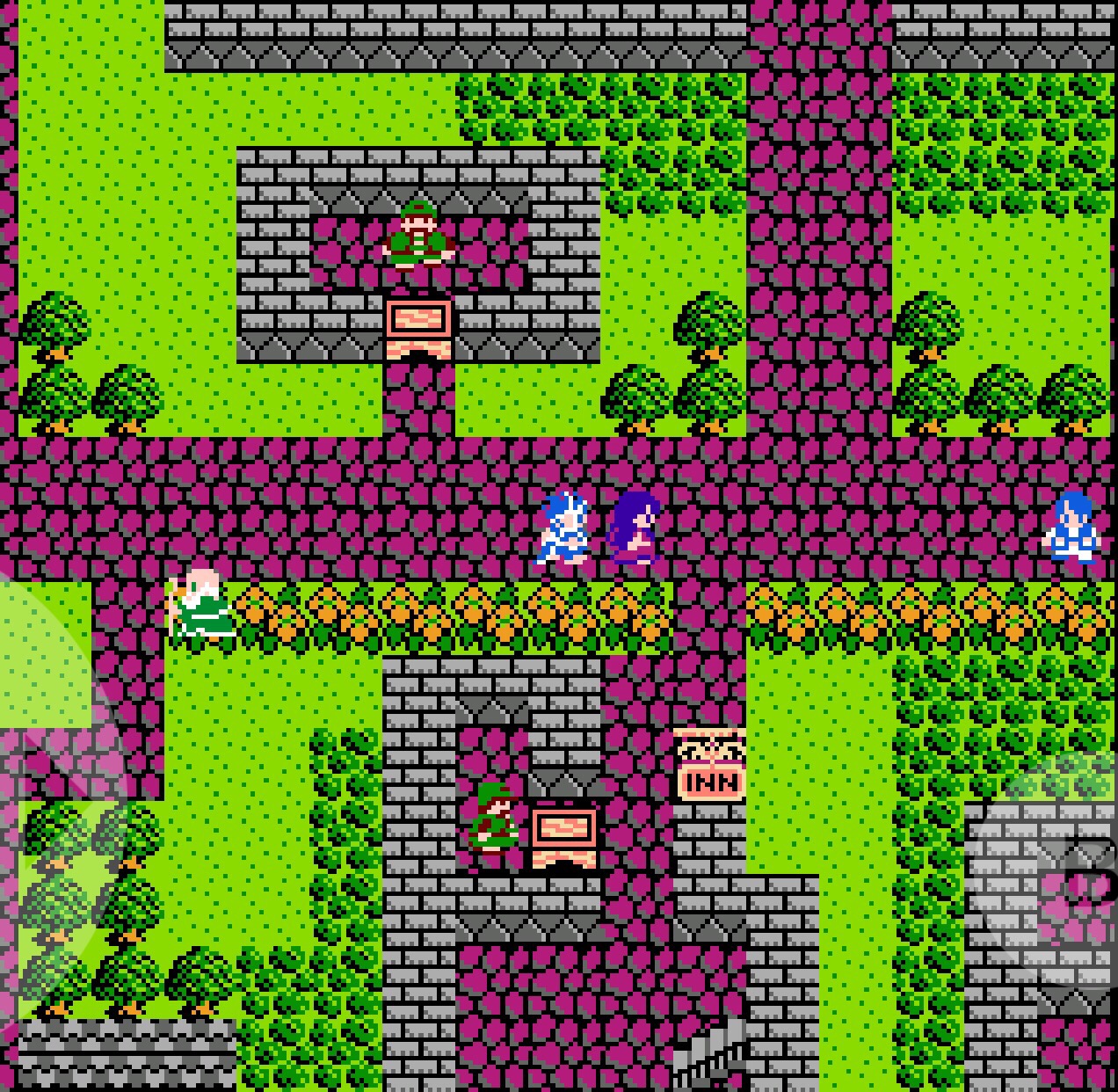

In keeping with the unusual structure, I’m also not going to start from the beginning. Rather, I think it’s more useful to start with the game that created the template and work back to its antecedents and inspirations. It’s generally agreed that Enix’s 1986 Famicom release Dragon Quest (known in America as Dragon Warrior) was the game that established the genre. While it’s far from the first RPG from Japan and most of its individual parts can be found in earlier titles, it was the first to bring those parts together into the format we now recognize as the JRPG. It may feel its age when you play it today, but Dragon Quest is clearly of the same family as, say, Persona 5, whereas something like Bokosuka Wars feels like something else almost entirely.

Dragon Quest was created by a young man by the name of Yuji Horii. In the 1980s, it wasn’t uncommon for companies like Enix to hold contests that basically served as try-outs to find new talent. Horii won one such contest in 1982 where part of the prize was a trip to the United States to attend AppleFest. While there, Horii got his first glimpse of Sir-Tech’s Wizardry series of RPGs. He was so fascinated by the game that he included a first-person section in the game he was working on at the time, an adventure game titled The Portopia Serial Murder Incident. While playing through one of those sections, you can find a note on the wall that reads “MONSTER SURPRISED YOU", a quote from Wizardry.

Dragon Quest was created by a young man by the name of Yuji Horii. In the 1980s, it wasn’t uncommon for companies like Enix to hold contests that basically served as try-outs to find new talent. Horii won one such contest in 1982 where part of the prize was a trip to the United States to attend AppleFest. While there, Horii got his first glimpse of Sir-Tech’s Wizardry series of RPGs. He was so fascinated by the game that he included a first-person section in the game he was working on at the time, an adventure game titled The Portopia Serial Murder Incident. While playing through one of those sections, you can find a note on the wall that reads “MONSTER SURPRISED YOU", a quote from Wizardry.

While Horii loved Wizardry and other CRPGs of the era such as Ultima and The Black Onyx, he wanted to make the genre more approachable for newcomers. Specifically, he wanted to make a game where even novice players could enjoy the feeling of following the story of a character who grew stronger as they played. Early RPGs were notoriously difficult, and Wizardry perhaps the most difficult of them all in its early installments. They were complex things, with tons of equipment, party members, magic spells, items, and so on to keep track of. For his game, Horii envisioned something that combined the exciting first-person battles of Wizardry, the overhead exploration of Ultima, the menu-based command system of his own Portopia, all streamlined into a straightforward experience. Dragon Quest also had the backing of a hot artist, Akira Toriyama (of Dragon Ball fame), and an experienced composer, Koichi Sugiyama. It took a little while for the game to catch on, but once it did the series ran away with success that it has yet to yield to this day.

As mentioned, however, there were earlier Japanese RPGs. Particularly on the various Japanese computer platforms, RPGs of various sorts were thriving. Publishers such as Koei and Falcom were building their reputations with each new release. At the same time, it’s hard to say whether Horii was influenced by their games or not when he created Dragon Quest. He’s been pretty candid about his inspirations, and they largely seem to be Western RPGs. As most of Falcom’s games tended to be action-RPGs and Koei’s titles helping to shape the tactical RPG sub-genre, I won’t labor much over them here. Important games to be sure, but perhaps not directly important to the JRPG sub-genre.

I do want to at least mention The Black Onyx from Bullet-Proof Software, however. Released in 1984 on the NEC PC-8801, The Black Onyx was one of the first original Japanese language RPGs to find any real measure of success in the market. In practice, it’s a fairly pedestrian take on the Wizardry concept of turn-based dungeon crawling, but it’s almost certain that Yuji Horii would have played the game prior to creating Dragon Quest. The Black Onyx did more to champion the very concept of video game RPGs in Japan than perhaps any other game did, blazing a trail for Dragon Quest and many other games in the future.

I do want to at least mention The Black Onyx from Bullet-Proof Software, however. Released in 1984 on the NEC PC-8801, The Black Onyx was one of the first original Japanese language RPGs to find any real measure of success in the market. In practice, it’s a fairly pedestrian take on the Wizardry concept of turn-based dungeon crawling, but it’s almost certain that Yuji Horii would have played the game prior to creating Dragon Quest. The Black Onyx did more to champion the very concept of video game RPGs in Japan than perhaps any other game did, blazing a trail for Dragon Quest and many other games in the future.

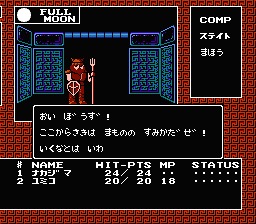

The success of Dragon Quest naturally led to copycats, homages, and competitors. In the long run, only a few of these opportunistic releases amounted to anything significant. Some of the more important ones arrived in 1987. Developer Atlus took their kick at the can with Digital Devil Story: Megami Tensei, based on a trilogy of popular science fiction novels written by Aya Nishitani. This was one of the earliest games in the genre that allowed to recruit your enemies. It’s also notable for kicking off the Megami Tensei brand of games, whose most recent release was this year’s Persona 5. It’s very likely Atlus wouldn’t be around today were it not for this game.

The success of Dragon Quest naturally led to copycats, homages, and competitors. In the long run, only a few of these opportunistic releases amounted to anything significant. Some of the more important ones arrived in 1987. Developer Atlus took their kick at the can with Digital Devil Story: Megami Tensei, based on a trilogy of popular science fiction novels written by Aya Nishitani. This was one of the earliest games in the genre that allowed to recruit your enemies. It’s also notable for kicking off the Megami Tensei brand of games, whose most recent release was this year’s Persona 5. It’s very likely Atlus wouldn’t be around today were it not for this game.

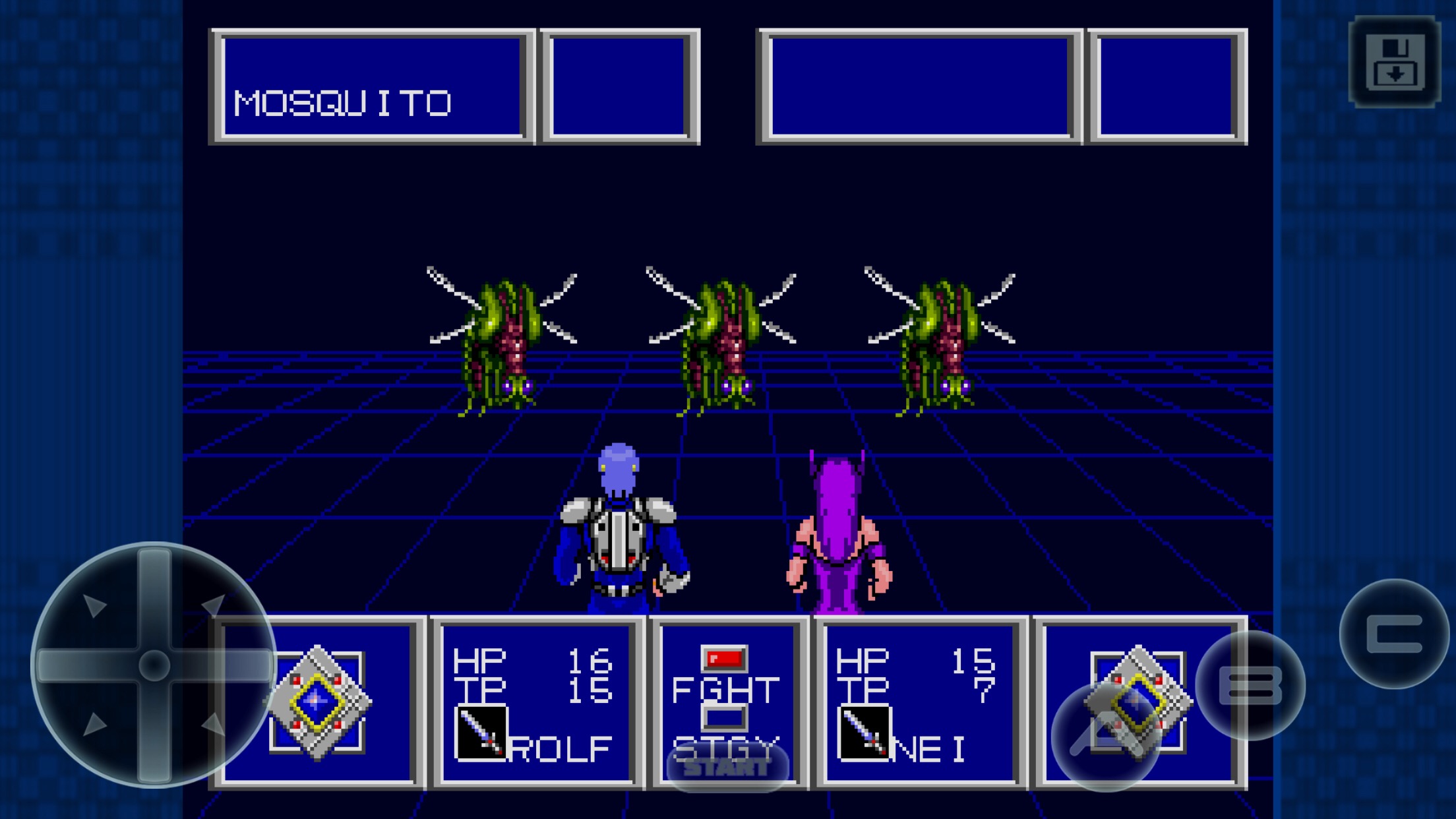

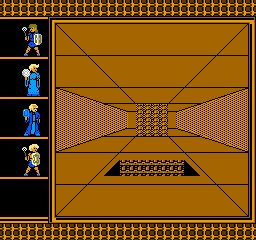

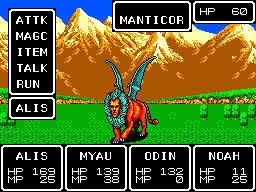

Over at SEGA, the company was fighting a losing battle with their Mark III console (known elsewhere as the Master System). Without much support from third-party publishers, SEGA more or less had to chase trends all on their own. Thus, if they needed an answer to Dragon Quest, they would have to provide it themselves. Interestingly, SEGA had ported The Black Onyx to their earlier SG-1000 console. Some of the people that worked on that port ended up contributing to SEGA’s first big salvo in the JRPG wars, Phantasy Star. While the series sort of evaporated after the 16-bit era and returned later as a multiplayer action-RPG, the early games were quite well-known and loved among Western fans of JRPGs.

Over at SEGA, the company was fighting a losing battle with their Mark III console (known elsewhere as the Master System). Without much support from third-party publishers, SEGA more or less had to chase trends all on their own. Thus, if they needed an answer to Dragon Quest, they would have to provide it themselves. Interestingly, SEGA had ported The Black Onyx to their earlier SG-1000 console. Some of the people that worked on that port ended up contributing to SEGA’s first big salvo in the JRPG wars, Phantasy Star. While the series sort of evaporated after the 16-bit era and returned later as a multiplayer action-RPG, the early games were quite well-known and loved among Western fans of JRPGs.

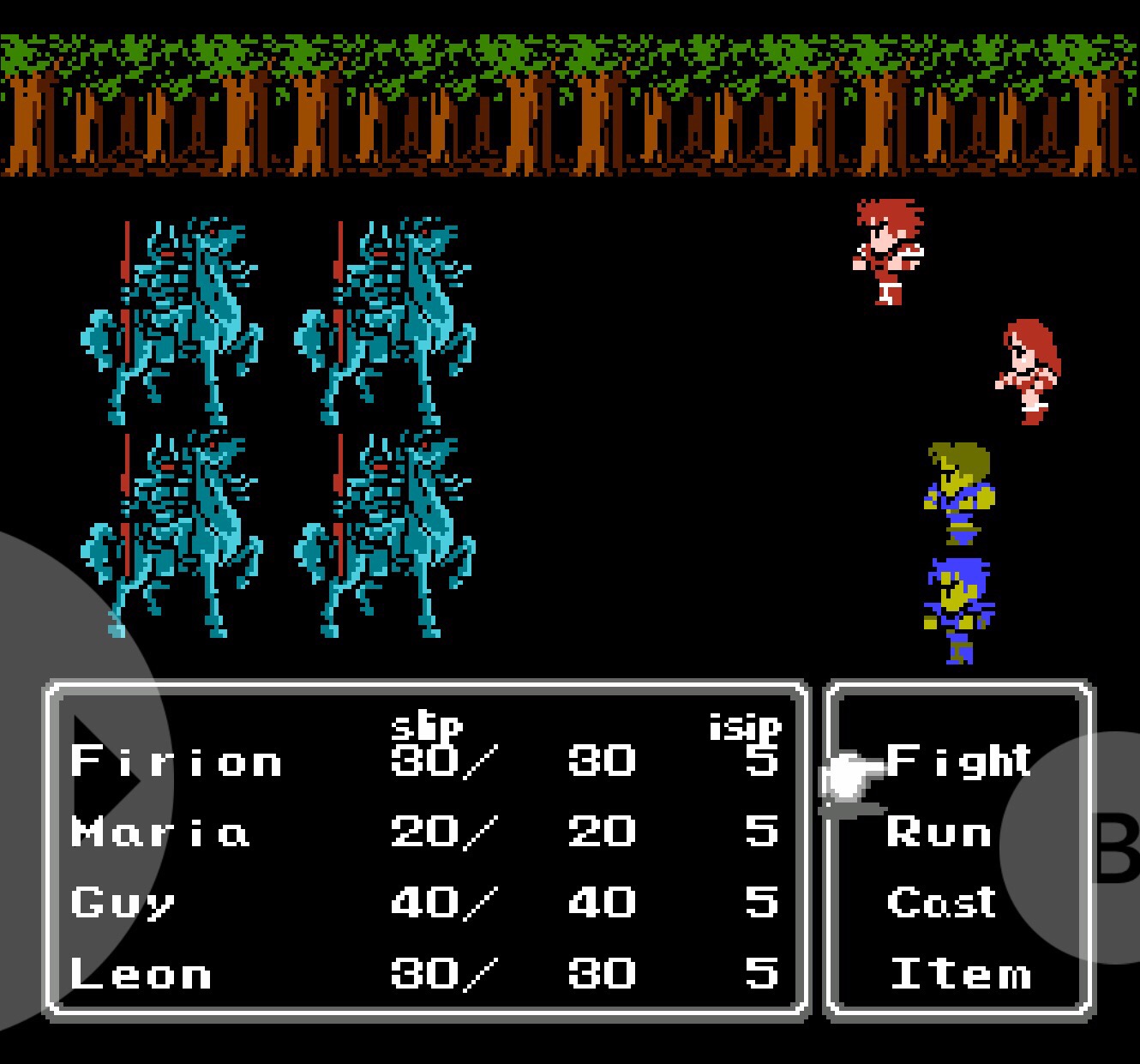

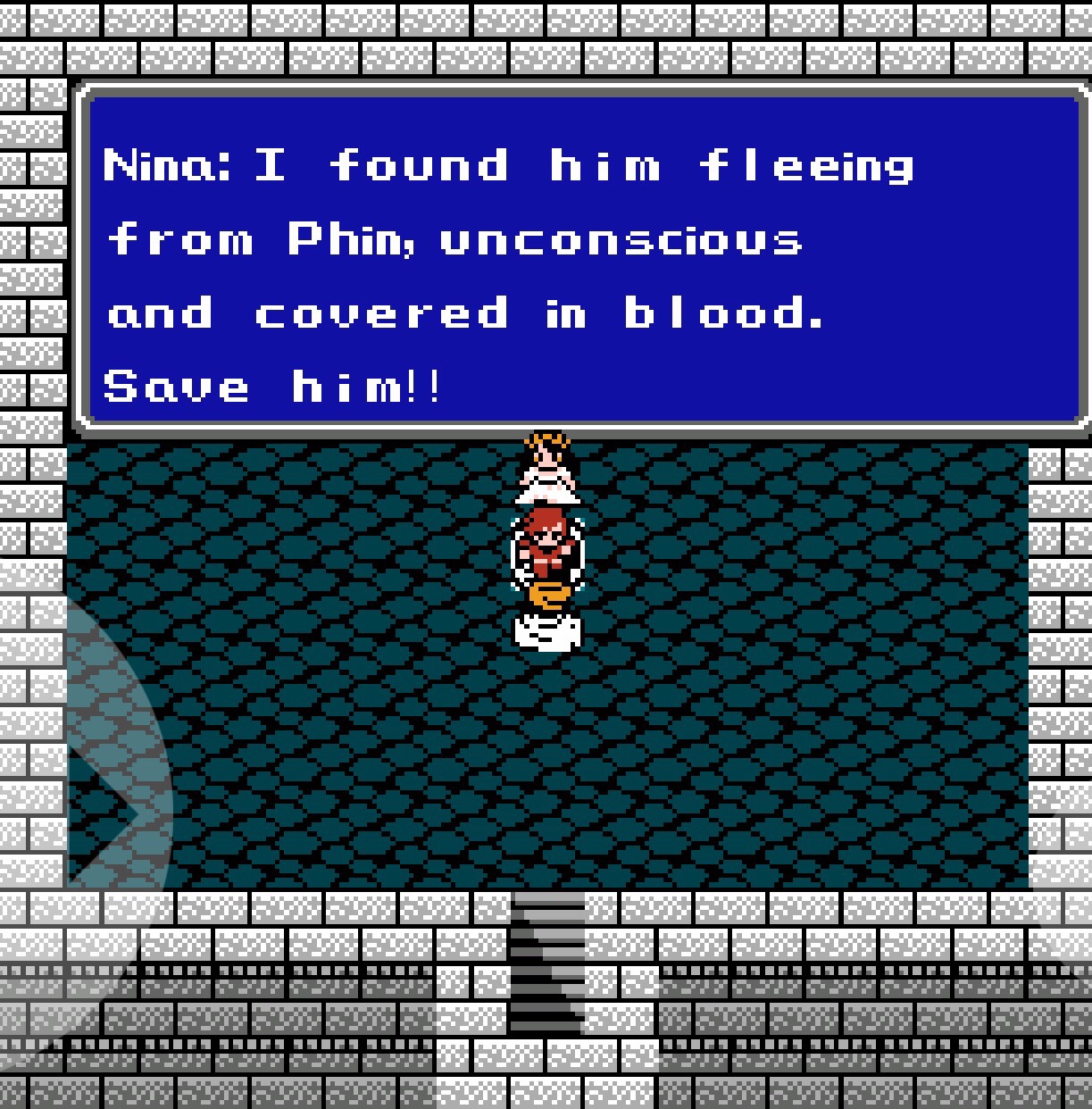

The most significant 1987 release, however, was Square’s Final Fantasy. While it was almost assuredly greenlit on the back of the successes of the first two Dragon Quest games, Final Fantasy seemed to draw almost as much from Dungeons & Dragons as it did from Dragon Quest. It gave players the chance to customize their party, put a heavier emphasis on story than Dragon Quest, and had a novel mid-game class promotion that helped sow the seeds for the popular job systems that would soon appear in many JRPGs. I should mention that early on Final Fantasy wasn’t much competition for Dragon Quest in its home country. It was successful, but the series wouldn’t really get on Dragon Quest‘s sales heels until Final Fantasy 7 arrived. It was at the very least a popular second choice in Japan, however, and as the series developed its identity it proved to have greater worldwide appeal, too.

The most significant 1987 release, however, was Square’s Final Fantasy. While it was almost assuredly greenlit on the back of the successes of the first two Dragon Quest games, Final Fantasy seemed to draw almost as much from Dungeons & Dragons as it did from Dragon Quest. It gave players the chance to customize their party, put a heavier emphasis on story than Dragon Quest, and had a novel mid-game class promotion that helped sow the seeds for the popular job systems that would soon appear in many JRPGs. I should mention that early on Final Fantasy wasn’t much competition for Dragon Quest in its home country. It was successful, but the series wouldn’t really get on Dragon Quest‘s sales heels until Final Fantasy 7 arrived. It was at the very least a popular second choice in Japan, however, and as the series developed its identity it proved to have greater worldwide appeal, too.

While I won’t be highlighting every game in the series, Dragon Quest 3 deserves special mention. Released in the beginning of 1988, it’s where the series became a cultural phenomenon. It was also significant for its mechanics, introducing a day/night cycle and the ability to multiclass your characters to create little powerhouses. It also has one of the better stories in the series, tying the first trilogy up with a neat little bow. Late in 1988, Final Fantasy 2 arrived. It was an odd game, mechanically speaking, but it also contained many elements that would go on to be mainstays in the franchise including named party members, a story of rebels versus an evil empire, chocobos, and even the Ultima magic spell. Its much-maligned gameplay systems would end up spawning their own spin-off soon enough.

While I won’t be highlighting every game in the series, Dragon Quest 3 deserves special mention. Released in the beginning of 1988, it’s where the series became a cultural phenomenon. It was also significant for its mechanics, introducing a day/night cycle and the ability to multiclass your characters to create little powerhouses. It also has one of the better stories in the series, tying the first trilogy up with a neat little bow. Late in 1988, Final Fantasy 2 arrived. It was an odd game, mechanically speaking, but it also contained many elements that would go on to be mainstays in the franchise including named party members, a story of rebels versus an evil empire, chocobos, and even the Ultima magic spell. Its much-maligned gameplay systems would end up spawning their own spin-off soon enough.

The SEGA Genesis had arrived late in 1988, and while it was never an RPG powerhouse like its rival, SEGA made a strong effort. Phantasy Star 2 arrived less than half a year after the console’s launch, and it was one of the first really great 16-bit JRPGs. Unlike the first game, whose first-person dungeon explorations paid clear homage to Wizardry, Phantasy Star 2 went with an overhead perspective at all times outside of battle. That makes it a far more conventional JRPG, but its unusual planet-hopping science-fiction theme and somewhat dark story make sure it isn’t lost in the crowd. Its dungeons are at times aggravatingly difficult to navigate, but if you pack some graph paper it can still be a lot of fun today.

The SEGA Genesis had arrived late in 1988, and while it was never an RPG powerhouse like its rival, SEGA made a strong effort. Phantasy Star 2 arrived less than half a year after the console’s launch, and it was one of the first really great 16-bit JRPGs. Unlike the first game, whose first-person dungeon explorations paid clear homage to Wizardry, Phantasy Star 2 went with an overhead perspective at all times outside of battle. That makes it a far more conventional JRPG, but its unusual planet-hopping science-fiction theme and somewhat dark story make sure it isn’t lost in the crowd. Its dungeons are at times aggravatingly difficult to navigate, but if you pack some graph paper it can still be a lot of fun today.

Nintendo was rolling out its own new hardware in 1989, but it wasn’t their 16-bit console. No, it was just one of the most successful pieces of gaming hardware of all-time. The Game Boy was the right machine at the right time for the right price, and while there are plenty of reasons for its success, its fine line-up of games was a big part of that. In its first year on the market, the Game Boy played host to the very first handheld JRPG, Makaitoshi SaGa (or Final Fantasy Legend, as it’s known in the West). It was developed under the guidance of the man behind Final Fantasy 2, and it kind of shows. It’s strange how his quirky ideas were more acceptable in a handheld format. While I’d never accuse the Game Boy of having an excess of quality RPGs, to the extent that it did, Makaitoshi SaGa led the way.

Nintendo was rolling out its own new hardware in 1989, but it wasn’t their 16-bit console. No, it was just one of the most successful pieces of gaming hardware of all-time. The Game Boy was the right machine at the right time for the right price, and while there are plenty of reasons for its success, its fine line-up of games was a big part of that. In its first year on the market, the Game Boy played host to the very first handheld JRPG, Makaitoshi SaGa (or Final Fantasy Legend, as it’s known in the West). It was developed under the guidance of the man behind Final Fantasy 2, and it kind of shows. It’s strange how his quirky ideas were more acceptable in a handheld format. While I’d never accuse the Game Boy of having an excess of quality RPGs, to the extent that it did, Makaitoshi SaGa led the way.

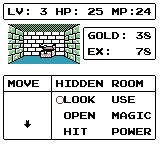

Before I close the curtain on the 1980s, however I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention The Sword of Hope. Not because it was highly successful or even influential, but because it was the second handheld video RPG ever, and it was made by Kemco. Yes, the same Kemco that sprays JRPGs all over the App Store and Google Play today. The Sword of Hope is a strange mix of first-person adventure a la Shadowgate and a variety of JRPG elements. Given Kemco’s status as one of the more prolific publishers of handheld JRPGs in recent times, I think The Sword of Hope has to be acknowledged to some extent.

Before I close the curtain on the 1980s, however I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention The Sword of Hope. Not because it was highly successful or even influential, but because it was the second handheld video RPG ever, and it was made by Kemco. Yes, the same Kemco that sprays JRPGs all over the App Store and Google Play today. The Sword of Hope is a strange mix of first-person adventure a la Shadowgate and a variety of JRPG elements. Given Kemco’s status as one of the more prolific publishers of handheld JRPGs in recent times, I think The Sword of Hope has to be acknowledged to some extent.

By the end of the 1980s, JRPGs were the biggest genre in Japan. They were also practically invisible outside of Japan, and not for lack of trying. It would be years before the genre would catch on outside of Japan, which meant the West missed out on a lot of great classics in the genre. We’ll be taking a look at some of those in the next part of this Glossary, along with the game that finally tore down the wall. You can look forward to a look at JRPGs in the 1990s next month. As for me, I’ll be back next week with another RPG Reload File. Wow, it’s been a long time! Thanks for reading!

Next Week’s Reload: Warhammer Quest ($2.99)