Hello, gentle readers, and welcome to the RPG Reload, the regular feature where we fight by slamming our bodies into things. To be specific, welcome to the RPG Reload Glossary, where we get all up in fussy semantics, history, and other things that polite society will shun us for. Having covered both social RPGs and tactical RPGs in previous installments, we now turn our attention to perhaps the most popular and hard-to-define sub-genre of RPGs: the action-RPG. You can expect this one to be another three- or four-parter, as trying to do it all at once would require some keen editing, and that is not a thing that I am good at. In today’s installment, we’ll be looking at the origins and early years of the genre, loosely covering the 1980s. Let’s get ready to rumble!

Hello, gentle readers, and welcome to the RPG Reload, the regular feature where we fight by slamming our bodies into things. To be specific, welcome to the RPG Reload Glossary, where we get all up in fussy semantics, history, and other things that polite society will shun us for. Having covered both social RPGs and tactical RPGs in previous installments, we now turn our attention to perhaps the most popular and hard-to-define sub-genre of RPGs: the action-RPG. You can expect this one to be another three- or four-parter, as trying to do it all at once would require some keen editing, and that is not a thing that I am good at. In today’s installment, we’ll be looking at the origins and early years of the genre, loosely covering the 1980s. Let’s get ready to rumble!

So, like before, I’m going to try to give a loose definition of what makes an action-RPG, in my opinion. You may disagree, but at the very least, you’ll know the filter through which I’m including things or excluding them. It’s a fairly short list compared to others, which may explain why this is such a slippery sub-genre in general.

Action-RPGs typically involve these traits:

- Real-time combat

- The character can be moved around freely by the player

- Attacks are mapped more or less one-to-one with clicks, taps, or button presses

- Defeating enemies yields experience points, which in turn earn character level-ups

- Leveling up increases the character’s stats and/or capabilities

- Character level should be an important part of success for the average player

- There should be a requirement for some degree of reflexive skill

- A persistent inventory system of some sort

- Generally (but not always) only one character under the player’s control at a time

Action-RPGs

- Ys

- Zelda 2: Adventure of Link

- Diablo

- Secret of Mana

- The World Ends With You

- The Witcher 3

- The Elder Scrolls 5: Skyrim

- Deus Ex

Not Action-RPGs (puts on helmet)

- The Legend of Zelda

- Call of Duty: Modern Warfare

- Super Metroid

- Monster Hunter Freedom Unite

- Enviro-Bear 2010

- Flappy Bird

Technically Action-RPGs but No, Stop

- Batman: Arkham City

- Devil May Cry

- Ninja Gaiden Black

- Horizon: Zero Dawn

- Bionic Commando

- Gradius

Okay, so you can see how this can get away from us. Also, some of you are probably heading down to the comments now to give me an earful about Monster Hunter or Zelda. I acknowledge that it’s really hard to define this genre, especially since adding RPG elements into every single game ever became a popular thing to do. It turns out that grinding experience for small rewards is a powerful psychological loop in any game, not just menu-driven ones. Live and learn! Now, just because a game doesn’t fall into the strict boundaries of the genre, it doesn’t mean it isn’t important to it. Probably one of the biggest influences on the genre is The Legend of Zelda, after all. Even if it doesn’t have experience points that lead to level-ups, it’s still an integral part of the sub-genre’s history, as we’ll soon see.

Unlike many other RPG sub-genres, action-RPGs don’t really owe much to tabletop games. Beyond tabletop gaming inspiring the RPG genre itself, anyway. Action-RPGs are perhaps one of the earliest cases of genre-mixing in video gaming. It was inevitable that someone would try to pair action’s chocolate with an RPG’s peanut butter. The only real surprise is in how many different ways developers would find to do it. This is another case where Eastern and Western game developers came to the genre at different times and in very distinct ways, in spite of having many of the same sources of inspiration. In fact, as we’re only covering the 1980s in this installment, we’re not going to see a lot of Western games at all. The Western game industry of the time had a tendency to treat action games and RPGs as separate things for separate demographics, and nary the twain should meet.

Still, the story does begin with a couple of Western games. Many game developer were (and are) big fans of games themselves, and it shows in their work. At one point in time, one of the hottest games around was 1977’s Colossal Cave Adventure, a text adventure that could be found in just about any computer lab across America and beyond. Many game developers of the time tried to offer up their own spin on it, giving us games like Zork, Rogue, and Mystery House on home computers. Developer Warren Robinett was not working with home computers, unfortunately. No, he was working at Atari on their Atari 2600 VCS console. Originally released in 1977, the console featured hardware specs that weren’t exactly ideal for memory-intensive RPGs or text adventures.

In making the 1980 release Adventure, Robinett had to interpret the game through graphics, and relatively simple ones at that. Compared to other games on the console at the time, it was incredibly complex. It featured 30 different rooms, multiple items to collect and use, and roaming enemies. There aren’t any experience points and your character never permanently becomes any stronger, but it’s hard to imagine that the game didn’t have at least some influence on action-RPGs to follow. Unfortunately, like many ambitious Atari 2600 games, this game hasn’t aged all that well. Your hero is a square, the dragons look like ducks, and bugs are waved away as evil magic. Nevertheless, it’s both impressive for its time and important historically.

In making the 1980 release Adventure, Robinett had to interpret the game through graphics, and relatively simple ones at that. Compared to other games on the console at the time, it was incredibly complex. It featured 30 different rooms, multiple items to collect and use, and roaming enemies. There aren’t any experience points and your character never permanently becomes any stronger, but it’s hard to imagine that the game didn’t have at least some influence on action-RPGs to follow. Unfortunately, like many ambitious Atari 2600 games, this game hasn’t aged all that well. Your hero is a square, the dragons look like ducks, and bugs are waved away as evil magic. Nevertheless, it’s both impressive for its time and important historically.

Things didn’t really get rolling until a few years later, however. The year 1983 saw a couple of important releases in the genre. First, the Gateway to Apshai was released across a handful of Western home computers, developed by The Connelly Group and published by Epyx. A prequel to Temple of Apshai, it featured real-time combat, the ability to improve your character’s stats, and loot a-plenty. This is probably the earliest game I’d feel comfortable calling an action-RPG. Like many games of its time, it doesn’t fit neatly into our modern genre classifications, but it’s close enough. Certainly closer than Bokosuka Wars, which came later in the year. Published by ASCII for the Japanese Sharp X1 computer, the game is frequently cited as a source of inspiration for TRPGs. Well, add another sub-genre to that list, I guess.

Things didn’t really get rolling until a few years later, however. The year 1983 saw a couple of important releases in the genre. First, the Gateway to Apshai was released across a handful of Western home computers, developed by The Connelly Group and published by Epyx. A prequel to Temple of Apshai, it featured real-time combat, the ability to improve your character’s stats, and loot a-plenty. This is probably the earliest game I’d feel comfortable calling an action-RPG. Like many games of its time, it doesn’t fit neatly into our modern genre classifications, but it’s close enough. Certainly closer than Bokosuka Wars, which came later in the year. Published by ASCII for the Japanese Sharp X1 computer, the game is frequently cited as a source of inspiration for TRPGs. Well, add another sub-genre to that list, I guess.

The following year is where things really started to break open for the genre in Japan. In June of 1984, Namco released The Tower of Druaga in arcades. The intention was to create a sort of fantasy version of Pac-Man, with puzzles to solve, monsters to battle, and hidden treasure to find. The game was a big hit and while its debatable how much of an influence it had on the next game in the list, it’s been cited as the inspiration for Hydlide and certainly seems to be an antecedent to The Legend of Zelda. Later in 1984, Nihon Falcom released Dragon Slayer for the Japanese PC-88. If you just looked at screenshots, Dragon Slayer would look for all the world like another spin on Rogue. The trick is that instead of things playing out in turn-based fashion, the action in Dragon Slayer is completely real-time.

The following year is where things really started to break open for the genre in Japan. In June of 1984, Namco released The Tower of Druaga in arcades. The intention was to create a sort of fantasy version of Pac-Man, with puzzles to solve, monsters to battle, and hidden treasure to find. The game was a big hit and while its debatable how much of an influence it had on the next game in the list, it’s been cited as the inspiration for Hydlide and certainly seems to be an antecedent to The Legend of Zelda. Later in 1984, Nihon Falcom released Dragon Slayer for the Japanese PC-88. If you just looked at screenshots, Dragon Slayer would look for all the world like another spin on Rogue. The trick is that instead of things playing out in turn-based fashion, the action in Dragon Slayer is completely real-time.

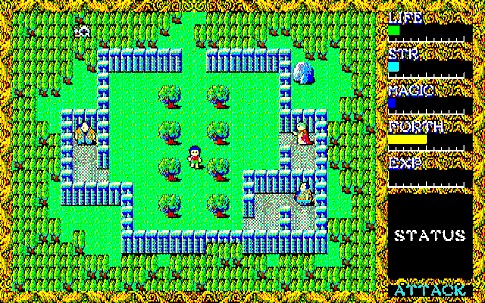

Dragon Slayer‘s chief rival was Hydlide, developed and published in late 1984 by T&E Soft. The Hydlide series fizzled out considerably more quickly and with far less dignity than Dragon Slayer, but it did allow players to get some virtual fresh air. Most action-RPGs and RPGs in general took place entirely in dungeons. Hydlide offered an overworld map area that players could traverse at their leisure, the first game of its type to do so. If you look at screenshots of Hydlide and squint a little, it’s not hard to see Zelda and Ys in there, even if the game itself wasn’t nearly as good as what was to follow. Unfortunately, most Western gamers are familiar with this game through its terrible NES port, which was originally released in Japan in 1986 but bafflingly brought to America in the summer of 1989, well after many of the games it ended up influencing.

Dragon Slayer‘s chief rival was Hydlide, developed and published in late 1984 by T&E Soft. The Hydlide series fizzled out considerably more quickly and with far less dignity than Dragon Slayer, but it did allow players to get some virtual fresh air. Most action-RPGs and RPGs in general took place entirely in dungeons. Hydlide offered an overworld map area that players could traverse at their leisure, the first game of its type to do so. If you look at screenshots of Hydlide and squint a little, it’s not hard to see Zelda and Ys in there, even if the game itself wasn’t nearly as good as what was to follow. Unfortunately, most Western gamers are familiar with this game through its terrible NES port, which was originally released in Japan in 1986 but bafflingly brought to America in the summer of 1989, well after many of the games it ended up influencing.

In 1985, both Dragon Slayer and Hydlide received sequels. Dragon Slayer 2: Xanadu incorporated more traditional role-playing elements, such as an assortment of NPCs, a world outside the dungeons, and even a basic morality system. The biggest change was that the exploration segments now took place in a side-scrolling view, complete with platforming. When your character made contact with an enemy, the battle would take place on a separate overhead screen. Xanadu is considered something of a prototype for Metroid-style exploratory platformers. The series is still alive today, with an English version of the PC Xanadu Next released several months ago and the latest game, Tokyo Xanadu, making an appearance on the PlayStation Vita and PlayStation 4.

In 1985, both Dragon Slayer and Hydlide received sequels. Dragon Slayer 2: Xanadu incorporated more traditional role-playing elements, such as an assortment of NPCs, a world outside the dungeons, and even a basic morality system. The biggest change was that the exploration segments now took place in a side-scrolling view, complete with platforming. When your character made contact with an enemy, the battle would take place on a separate overhead screen. Xanadu is considered something of a prototype for Metroid-style exploratory platformers. The series is still alive today, with an English version of the PC Xanadu Next released several months ago and the latest game, Tokyo Xanadu, making an appearance on the PlayStation Vita and PlayStation 4.

Hydlide‘s sequel didn’t fare quite so well. Hydlide 2: Shine of Darkness adopted an unusual morality system that was based on which types of enemies you killed. Depending on your alignment, you would be able to get different equipment, dialogue, and so on. Townspeople weren’t exactly eager to work with evil characters, for example. Hydlide would receive a third installment in 1989 before taking a long break. It was simultaneously revived and buried with the absolutely dreadful Virtual Hydlide, a SEGA Saturn remake of Hydlide that tried to do a behind-the-back 3D world in just about the worst way I’ve ever seen. Somehow, it got an English release from Atlus.

Over in America, 1985 saw the release of Atari’s arcade action game Gauntlet. While it was almost entirely bereft of RPG elements, you can clearly see the roots of many a hack-and-slash dungeon crawler in it. Up to four players can play at once, and cooperation is the key to survival. Gauntlet itself was directly inspired by a 1983 Atari 8-bit computer game called Dandy. That game lacked the multiple character types of Gauntlet, however. Gauntlet was a smash hit and served as one of the most accessible and popular dungeon-crawlers of its era, getting sequels and ports to just about every viable piece of hardware around. It’s also one of the more egregious examples of pay-to-win you can find in an arcade thanks to its crushing difficulty and eternally-hungry player characters. Later games in the series would incorporate RPG elements, though it never really got all that dense.

Over in America, 1985 saw the release of Atari’s arcade action game Gauntlet. While it was almost entirely bereft of RPG elements, you can clearly see the roots of many a hack-and-slash dungeon crawler in it. Up to four players can play at once, and cooperation is the key to survival. Gauntlet itself was directly inspired by a 1983 Atari 8-bit computer game called Dandy. That game lacked the multiple character types of Gauntlet, however. Gauntlet was a smash hit and served as one of the most accessible and popular dungeon-crawlers of its era, getting sequels and ports to just about every viable piece of hardware around. It’s also one of the more egregious examples of pay-to-win you can find in an arcade thanks to its crushing difficulty and eternally-hungry player characters. Later games in the series would incorporate RPG elements, though it never really got all that dense.

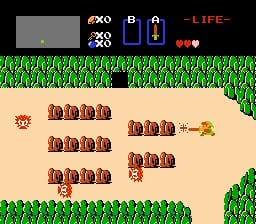

The proverbial shot heard ’round the world first arrived in 1986. Nintendo’s The Legend of Zelda hit Nintendo’s 8-bit console in Japan in early 1986, building on games like Dragon Slayer, Druaga, and Hydlide with an enormous open world, more complex puzzles, and an innovation that will probably seem quaint to younger readers: an attack button. Up until this point, most Japanese action-RPGs had players engage enemies by bumping into them with their character. Zelda gave the player a distinct button for swinging their weapon, something that seems obvious in hindsight. While the game wouldn’t launch in North America until the following year, it was an absolute sensation on both sides of the Pacific. The game’s lack of experience points and experience-based level-ups mean it’s not technically an RPG, if you ask me, but that didn’t stop it from inspiring a nearly uncountable number of games that do fit the definition.

The proverbial shot heard ’round the world first arrived in 1986. Nintendo’s The Legend of Zelda hit Nintendo’s 8-bit console in Japan in early 1986, building on games like Dragon Slayer, Druaga, and Hydlide with an enormous open world, more complex puzzles, and an innovation that will probably seem quaint to younger readers: an attack button. Up until this point, most Japanese action-RPGs had players engage enemies by bumping into them with their character. Zelda gave the player a distinct button for swinging their weapon, something that seems obvious in hindsight. While the game wouldn’t launch in North America until the following year, it was an absolute sensation on both sides of the Pacific. The game’s lack of experience points and experience-based level-ups mean it’s not technically an RPG, if you ask me, but that didn’t stop it from inspiring a nearly uncountable number of games that do fit the definition.

Of course, that includes its sequel, 1987’s Zelda 2: The Adventure of Link. Taking a page from Xanadu‘s book, Zelda 2 ditched the overhead action from the first game in favor of a side-scrolling view with platforming elements. Unlike Xanadu, however, it maintained the side-scrolling perspective even when battling enemies. It reserved its overhead view solely for exploring the overworld. Zelda 2 is also the only game in the series to give the player experience points for killing enemies, allowing the player to exchange them in various amounts for permanent stat upgrades for Link. It’s generally considered the black sheep of the series, but I’m rather fond of it myself. While Nintendo would never make another Zelda game like this one again, it was popular enough to start a little cottage industry of Zelda 2-inspired games. Amusingly enough, Xanadu would adopt its approach to combat when it made its way to the NES via Hudson’s Faxanadu later in 1987.

Of course, that includes its sequel, 1987’s Zelda 2: The Adventure of Link. Taking a page from Xanadu‘s book, Zelda 2 ditched the overhead action from the first game in favor of a side-scrolling view with platforming elements. Unlike Xanadu, however, it maintained the side-scrolling perspective even when battling enemies. It reserved its overhead view solely for exploring the overworld. Zelda 2 is also the only game in the series to give the player experience points for killing enemies, allowing the player to exchange them in various amounts for permanent stat upgrades for Link. It’s generally considered the black sheep of the series, but I’m rather fond of it myself. While Nintendo would never make another Zelda game like this one again, it was popular enough to start a little cottage industry of Zelda 2-inspired games. Amusingly enough, Xanadu would adopt its approach to combat when it made its way to the NES via Hudson’s Faxanadu later in 1987.

Speaking of Falcom games, they were on fire during this period. In addition to Faxanadu, Falcom also had their name attached to Dragon Slayer 4: Legacy of the Wizard, an extremely tough, side-scrolling, open-world action-RPG. In Legacy of the Wizard, you had multiple playable characters. You needed to make use of all of them to beat the game. Sneaking in at the end of the year was Dragon Slayer 5: Sorcerian, a unique action-RPG where you controlled a party of four heroes at once. It’s another side-scroller, but with a really unusual set-up where you would play discrete missions rather than wander around a big world. This was also an early episodic game, as disks containing new missions were distributed after its initial release.

Speaking of Falcom games, they were on fire during this period. In addition to Faxanadu, Falcom also had their name attached to Dragon Slayer 4: Legacy of the Wizard, an extremely tough, side-scrolling, open-world action-RPG. In Legacy of the Wizard, you had multiple playable characters. You needed to make use of all of them to beat the game. Sneaking in at the end of the year was Dragon Slayer 5: Sorcerian, a unique action-RPG where you controlled a party of four heroes at once. It’s another side-scroller, but with a really unusual set-up where you would play discrete missions rather than wander around a big world. This was also an early episodic game, as disks containing new missions were distributed after its initial release.

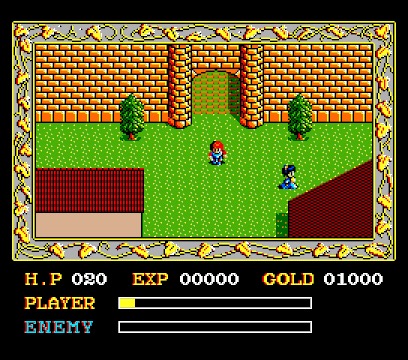

Falcom’s most important 1987 release wasn’t connected to Dragon Slayer at all, however. Ys: Ancient Ys Vanished released on the PC-8801 in the summer of 1987. Its exciting gameplay, strong emphasis on story, and outstanding soundtrack made it one of the most popular computer games of all-time in Japan. As a result of its popularity, it has been ported to virtually everything a game can be ported to. While it has never been able to find much success outside of Japan, the series still enjoys a healthy niche audience to this day, with the latest title, Ys 8, releasing on PlayStation Vita and PlayStation 4. Ys definitely leans more into the action aspects than some action-RPGs, but that’s part of what makes it so fun to play.

Falcom’s most important 1987 release wasn’t connected to Dragon Slayer at all, however. Ys: Ancient Ys Vanished released on the PC-8801 in the summer of 1987. Its exciting gameplay, strong emphasis on story, and outstanding soundtrack made it one of the most popular computer games of all-time in Japan. As a result of its popularity, it has been ported to virtually everything a game can be ported to. While it has never been able to find much success outside of Japan, the series still enjoys a healthy niche audience to this day, with the latest title, Ys 8, releasing on PlayStation Vita and PlayStation 4. Ys definitely leans more into the action aspects than some action-RPGs, but that’s part of what makes it so fun to play.

One curious but significant action-RPG that you might not think of as an action-RPG also released in 1987. Castlevania 2: Simon’s Quest fits all of the qualifications to be considered a card-carrying member of the sub-genre. Simon Belmont travels around an open world with a day-night cycle, gathering items, talking to NPCs, and battling enemies to earn hearts that can be exchanged for various permanent upgrades and items. The Castlevania series would largely shift from being straight action-platformers to exploratory action-RPGs with the release of Symphony of the Night in 1997, making Simon’s Quest something of an unexpected omen for the franchise’s future. I still have no clue where the Graveyard Duck is, though.

One curious but significant action-RPG that you might not think of as an action-RPG also released in 1987. Castlevania 2: Simon’s Quest fits all of the qualifications to be considered a card-carrying member of the sub-genre. Simon Belmont travels around an open world with a day-night cycle, gathering items, talking to NPCs, and battling enemies to earn hearts that can be exchanged for various permanent upgrades and items. The Castlevania series would largely shift from being straight action-platformers to exploratory action-RPGs with the release of Symphony of the Night in 1997, making Simon’s Quest something of an unexpected omen for the franchise’s future. I still have no clue where the Graveyard Duck is, though.

Also in 1987, Westone and SEGA’s Wonder Boy got a sequel called Wonder Boy in Monster Land that largely tossed out the twitchy platforming action of the original game in favor of a more deliberately-paced action-RPG set-up. While there was still plenty of jumping and dodging, this take on Wonder Boy saw the hero collecting equipment, gathering coins, and earning permanent upgrades. Of course, since it was still an arcade game first and foremost, this was an action-RPG with a timer ticking down at all times. The Monster World series would continue on for a few more installments. It has seen a lot of attention recently thanks to a stellar remake of one of the games in the series and an upcoming spiritual successor.

Also in 1987, Westone and SEGA’s Wonder Boy got a sequel called Wonder Boy in Monster Land that largely tossed out the twitchy platforming action of the original game in favor of a more deliberately-paced action-RPG set-up. While there was still plenty of jumping and dodging, this take on Wonder Boy saw the hero collecting equipment, gathering coins, and earning permanent upgrades. Of course, since it was still an arcade game first and foremost, this was an action-RPG with a timer ticking down at all times. The Monster World series would continue on for a few more installments. It has seen a lot of attention recently thanks to a stellar remake of one of the games in the series and an upcoming spiritual successor.

Over in the Western PC gaming scene, we finally get another action-RPG. The Faery Tale Adventure, from Microillusions, launched on the Commodore Amiga in 1987, bringing with it the largest explorable world in an RPG at that time. It’s a top-down action-RPG of the sort we would see a lot of in the 1990s, and in that respect, it certainly deserves credit for being ahead of the curve by a good bit. Something of a beginner’s RPG by design, it’s huge, empty, kind of shallow all around, but nevertheless beloved by some.

Over in the Western PC gaming scene, we finally get another action-RPG. The Faery Tale Adventure, from Microillusions, launched on the Commodore Amiga in 1987, bringing with it the largest explorable world in an RPG at that time. It’s a top-down action-RPG of the sort we would see a lot of in the 1990s, and in that respect, it certainly deserves credit for being ahead of the curve by a good bit. Something of a beginner’s RPG by design, it’s huge, empty, kind of shallow all around, but nevertheless beloved by some.

The next year was somewhat quieter. Ys 2 was released, completing the story that began in the first game. It added magic to the gameplay, turning it into a weird shooter/RPG hybrid for many of the bosses. The controversial side-scrolling series Exile, from Telenet, also debuted in 1988. The series follows the adventures of a time-traveling Syrian assassin who goes to different eras of real history to kill actual groups that existed at that time. The first game, which was never released outside of Japan, ended with the main character traveling to the 20th century and assassinating the leaders of the Soviet Union and the United States. Also, instead of potions and herbs, the main character uses an assortment of actual drugs like LSD and magic mushrooms to medicate himself. Working Designs would release some of the sequels in English markets, albeit with some careful changes.

Ultima series creators Origin Systems dipped their toe into the action-RPG waters in 1988 with the release of Times of Lore, a somewhat forgettable top-down RPG that nevertheless appears to have paved the way for more action-oriented Ultima titles in the future. In general, PC gamers were starting to get more accepting of action games, even the RPG players. 1987’s Dungeon Master, while not strictly a real-time game, had done much for convincing people of the excitement that more lively combat could sometimes offer. Naturally, it was too soon for that game to influence Times of Lore, which instead seems to have drawn from The Legend of Zelda. Filtered through an Origin Systems lens, anyway. But Dungeon Master would soon show its effects on the house that Ultima built in grand fashion. More on that one in the next feature.

Ultima series creators Origin Systems dipped their toe into the action-RPG waters in 1988 with the release of Times of Lore, a somewhat forgettable top-down RPG that nevertheless appears to have paved the way for more action-oriented Ultima titles in the future. In general, PC gamers were starting to get more accepting of action games, even the RPG players. 1987’s Dungeon Master, while not strictly a real-time game, had done much for convincing people of the excitement that more lively combat could sometimes offer. Naturally, it was too soon for that game to influence Times of Lore, which instead seems to have drawn from The Legend of Zelda. Filtered through an Origin Systems lens, anyway. But Dungeon Master would soon show its effects on the house that Ultima built in grand fashion. More on that one in the next feature.

The 1980s came to a close with a couple of sequels and the debut of two interesting new series. Wonder Boy in Monster Land got a follow-up in the form of the sublime Wonder Boy 3: The Dragon’s Trap. Designed as a console game rather than an arcade game, it’s able to embrace its RPG and adventure aspects in a far more enjoyable way. Ys follows in the footsteps of its sister series Dragon Slayer by making the jump to side-scrolling action with Ys 3: Wanderers from Ys. This game would later be remade as a top-down action-RPG named Ys: The Oath in Felghana.

The 1980s came to a close with a couple of sequels and the debut of two interesting new series. Wonder Boy in Monster Land got a follow-up in the form of the sublime Wonder Boy 3: The Dragon’s Trap. Designed as a console game rather than an arcade game, it’s able to embrace its RPG and adventure aspects in a far more enjoyable way. Ys follows in the footsteps of its sister series Dragon Slayer by making the jump to side-scrolling action with Ys 3: Wanderers from Ys. This game would later be remade as a top-down action-RPG named Ys: The Oath in Felghana.

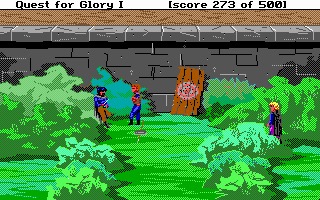

Meanwhile, on the TurboGrafx-16, Hudson was jumping into the multiplayer action-RPG pool that Gauntlet had been wading into. Dungeon Explorer allowed up to five players to battle their way through several dungeons. Each of the character types has unique abilities, and you can even unlock more as you play the game. It’s still quite a bit of fun, and the Wii Virtual Console version allows you to play with a full five players provided you own a Gamecube controller. Over in the West, the delightful Quest for Glory made its debut on PC. To be honest, the action combat bits are the worst part of the game by far, but it’s an excellent, imaginative game that kicked off an excellent series of RPG adventures. Is it a full-on action-RPG? No, not really, but allow me this technicality.

Meanwhile, on the TurboGrafx-16, Hudson was jumping into the multiplayer action-RPG pool that Gauntlet had been wading into. Dungeon Explorer allowed up to five players to battle their way through several dungeons. Each of the character types has unique abilities, and you can even unlock more as you play the game. It’s still quite a bit of fun, and the Wii Virtual Console version allows you to play with a full five players provided you own a Gamecube controller. Over in the West, the delightful Quest for Glory made its debut on PC. To be honest, the action combat bits are the worst part of the game by far, but it’s an excellent, imaginative game that kicked off an excellent series of RPG adventures. Is it a full-on action-RPG? No, not really, but allow me this technicality.

So what can we glean from the first decade of action-RPGs? Well, it’s interesting that in spite of there being quite a large number of games in the sub-genre, nobody quite hit on a template that everyone was willing to follow. There was no defining game in the sub-genre, and in a lot of ways, there never would be. At best, things ended up boiling down to a few distinct types of action-RPGs thanks to a few really heavy hitters. We’ll be encountering some of those in next week’s installment of the RPG Reload Glossary, covering action-RPGs in the 1990s. Thanks for reading!

Next Week’s Reload: Action-RPGs in the 1990s