Hello, gentle readers, and welcome to the RPG Reload, the regular feature where RPGs are as easy as A-B-C. Last month, we tried out a new style of article called the RPG Reload Glossary. It was conceived as a way to talk about specifics of the genre, define certain things, and occasionally even answer questions, all without the need to focus on one particular game. For the debut, I opted to go for a direct definition. This month, I’m going with something a little more vague, but I hope you all find it interesting nonetheless. If you have any topics you’d like to see covered in the future, you can let me know by posting in the comments below, stopping by the Official RPG Reload Club thread in the forums, or by tweeting me at @RPGReload.

Hello, gentle readers, and welcome to the RPG Reload, the regular feature where RPGs are as easy as A-B-C. Last month, we tried out a new style of article called the RPG Reload Glossary. It was conceived as a way to talk about specifics of the genre, define certain things, and occasionally even answer questions, all without the need to focus on one particular game. For the debut, I opted to go for a direct definition. This month, I’m going with something a little more vague, but I hope you all find it interesting nonetheless. If you have any topics you’d like to see covered in the future, you can let me know by posting in the comments below, stopping by the Official RPG Reload Club thread in the forums, or by tweeting me at @RPGReload.

This time around, we’re taking a look at one of the more popular RPG hybrid genres. Depending on where you’re coming from, this particular genre may carry a slightly different name. To Japanese players and many console gamers, this category is known as the SRPG. Now, I’m sure I don’t need to tell anyone what the ‘RPG’ part means, but ask what the ‘S’ stands for and you’ll again get different answers. The first group will tell you it’s for ‘simulation’, while the latter will probably offer up ‘strategy’. For those coming from a computer gaming background, this genre is most likely known as the TRPG, where the ‘T’ stands for ‘tactical’ or ‘tactics’. Though I personally tend to use ‘SRPG’ in my daily writing, for the purposes of this article I’m going to use ‘TRPG’, just to give some fair representation to the other team.

Whatever you call this genre, it’s not hard to conjure up some examples. For mobile gamers in particular, this has been a rich source of large, deep gameplay experiences that conventional wisdom would try to tell us are wholly incompatible with the platform. X-COM, Final Fantasy Tactics, Kingturn RPG, and even more casual takes like Fire Emblem Heroes are all examples of the genre that have enjoyed popularity among mobile fans. The genre tends to go in cycles of popularity, and at this particular moment in gaming, it feels like we’re at the top of a pretty big wave. I thought this might be a good time to look at the origins of the TRPG genre in video gaming and some of its bigger highlights up to today. It’s a rather large topic, so this article is only going to cover the early period up to 1990. I’ll conclude the history next week.

I don’t think I’ll be surprising anyone by saying that the TRPG genre originated in classic tabletop wargaming. I mean, it’s a hybrid, right? So it had to come from one or the other of those things in its name. What is interesting (although perhaps also not surprising to dedicated RPG fans) is that the TRPG technically predates the RPG, which sprang forth from precisely the same origins. Before we go any deeper, though, it’s probably a good idea to define what a TRPG is. As always, genre definitions can get fuzzy on the borderlines, so please don’t take this as the only possible word. It’s simply my interpretation, and flawed though it may be, it’s the one I’ll be using here.

TRPGs:

- are largely composed of turn-based battles between two or more groups of units

- feature units who can earn experience points and level up, becoming stronger over the course of the game

- typically feature equipment or gear that can be equipped to units to increase their capabilities

- can offer a variety of conditions for victory, though the most common are eliminating the enemy forces or securing a particular location

- generally focus on battles rather than any sort of real exploration, though there are exceptions

- often feature many different types of units with their own strengths and weaknesses

- are generally played out on grid-based maps where terrain has at least a minor effect on outcomes

- tend to focus on ground-level battles between individuals rather than abstracts groups of troops

- place a great degree of importance on unit positioning

- feature random elements that add an element of uncertainty as to the outcome of individual actions

- contain a number of different maps to battle on

- tend to tell an over-arching story that provides context for the battles

- often feature defined characters as units, but not always

- generally get more difficult as the player progresses through the maps

- may require the player to manage resources like items or money over the course of the entire game

Prominent Examples of TRPGs:

- Fire Emblem

- X-COM: Enemy Within

- Final Fantasy Tactics

- Demon’s Rise

- Kingturn RPG

- The Banner Saga

Not TRPGs:

- Advance Wars

- Warcraft 2

- Chess

- My Horse Prince

- Enviro-Bear 2010

- Battle Academy

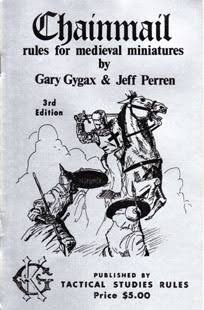

With that messy business out of the way, it’s time to step into our personal conceptualization of a time machine and set the dials to the early 1970s. Tabletop wargaming was in the midst of a climb to what would be one of its most popular periods before video games came and caused all kinds of trouble. We’re going to start this journey with Dave Arneson, co-creator of Dungeons & Dragons, though it’s worth mentioning that his efforts also had precedents. Many RPG fans are familiar with the names Gary Gygax and Dungeons & Dragons, I expect, but there were a couple of important links for the TRPG genre between tabletop wargames and Gygax and Arneson’s most famous work. From Gygax, there’s the obvious: Chainmail, the ground-breaking miniature wargame that would serve as the foundation of the mechanics of Dungeons & Dragons. Of particular interest to our topic is its rules for man-to-man combat and its fantasy supplement, which added heroes, magic, fantasy creatures, and magical equipment to the otherwise realistic game.

With that messy business out of the way, it’s time to step into our personal conceptualization of a time machine and set the dials to the early 1970s. Tabletop wargaming was in the midst of a climb to what would be one of its most popular periods before video games came and caused all kinds of trouble. We’re going to start this journey with Dave Arneson, co-creator of Dungeons & Dragons, though it’s worth mentioning that his efforts also had precedents. Many RPG fans are familiar with the names Gary Gygax and Dungeons & Dragons, I expect, but there were a couple of important links for the TRPG genre between tabletop wargames and Gygax and Arneson’s most famous work. From Gygax, there’s the obvious: Chainmail, the ground-breaking miniature wargame that would serve as the foundation of the mechanics of Dungeons & Dragons. Of particular interest to our topic is its rules for man-to-man combat and its fantasy supplement, which added heroes, magic, fantasy creatures, and magical equipment to the otherwise realistic game.

Even with all of that, however, Chainmail was closer to a straight wargame than what we’re looking for. The missing piece came from Dave Arneson, who used Chainmail and its fantasy supplement in a campaign he called Blackmoor. This setting had players taking on the roles of characters and going on adventures in dungeons and so on. Chainmail‘s rules were used to resolve combat situations. Blackmoor was a hit with its players, so much so that they were sad to see the game end each time. Arneson had the idea to add experience points to the game that players could collect over multiple playthroughs. Eventually, their characters would level up, becoming stronger. And now we’ve basically arrived at Dungeons & Dragons, haven’t we? The foundation of RPGs as we know them is essentially a turn-based strategy game with experience points and levels added to it, which is the blueprint for a TRPG to a tee.

Even with all of that, however, Chainmail was closer to a straight wargame than what we’re looking for. The missing piece came from Dave Arneson, who used Chainmail and its fantasy supplement in a campaign he called Blackmoor. This setting had players taking on the roles of characters and going on adventures in dungeons and so on. Chainmail‘s rules were used to resolve combat situations. Blackmoor was a hit with its players, so much so that they were sad to see the game end each time. Arneson had the idea to add experience points to the game that players could collect over multiple playthroughs. Eventually, their characters would level up, becoming stronger. And now we’ve basically arrived at Dungeons & Dragons, haven’t we? The foundation of RPGs as we know them is essentially a turn-based strategy game with experience points and levels added to it, which is the blueprint for a TRPG to a tee.

Of course, Dungeons & Dragons went beyond that relatively simple structure, incorporating social elements, lots of non-battle scenes, and so on. It’s well-known that Dungeons & Dragons served as the basis from which RPG video games were born, to the point that some of the earliest games in the genre, like 1974’s dnd, didn’t even try to hide their inspiration. For the first several years, video game RPGs handled combat in a largely similar fashion: they ripped the rules from Chainmail as closely as they could manage and presented it in a first-person view. Most of these early RPGs only allowed the player control of a single character. One of the first popular examples of giving the player control of a party of heroes was 1981’s Wizardry: Proving Grounds of the Mad Overlord. This gets us a little closer to our goal, but there’s still more exploration than combat, and battles don’t do much to take positioning or the terrain into account.

Of course, Dungeons & Dragons went beyond that relatively simple structure, incorporating social elements, lots of non-battle scenes, and so on. It’s well-known that Dungeons & Dragons served as the basis from which RPG video games were born, to the point that some of the earliest games in the genre, like 1974’s dnd, didn’t even try to hide their inspiration. For the first several years, video game RPGs handled combat in a largely similar fashion: they ripped the rules from Chainmail as closely as they could manage and presented it in a first-person view. Most of these early RPGs only allowed the player control of a single character. One of the first popular examples of giving the player control of a party of heroes was 1981’s Wizardry: Proving Grounds of the Mad Overlord. This gets us a little closer to our goal, but there’s still more exploration than combat, and battles don’t do much to take positioning or the terrain into account.

With how poorly-documented the early days of gaming are, it’s hard to nail down who exactly hit on the now-familiar TRPG style of combat first in video games. It’s also exceptionally difficult to say whether any of the earliest examples hit on the idea independently or if they influenced each other somehow. At any rate, there are two strong contenders to consider, along with a third that certainly popularized the system. At some point in 1982, Texas Instruments released a game for their TI-99/4A computer called Tunnels of Doom. Developed by Kevin Kenney, it features first-person dungeon-crawling with separate combat screens that place the player’s party and the monsters on a grid-based board. Some units can attack from a distance, others can use magic, and so on. This is most likely the first game to use this TRPG-style system in a video game.

With how poorly-documented the early days of gaming are, it’s hard to nail down who exactly hit on the now-familiar TRPG style of combat first in video games. It’s also exceptionally difficult to say whether any of the earliest examples hit on the idea independently or if they influenced each other somehow. At any rate, there are two strong contenders to consider, along with a third that certainly popularized the system. At some point in 1982, Texas Instruments released a game for their TI-99/4A computer called Tunnels of Doom. Developed by Kevin Kenney, it features first-person dungeon-crawling with separate combat screens that place the player’s party and the monsters on a grid-based board. Some units can attack from a distance, others can use magic, and so on. This is most likely the first game to use this TRPG-style system in a video game.

Dragon and Princess

Another possibility, albeit an outside one, is Koei’s Dragon and Princess, the very first RPG developed in Japan. This was released on NEC’s PC-8001 computer in 1982, and I’ve seen at least one source that says it came out in December of that year. That would likely put it after the release of Tunnels of Doom. It’s an interesting game. Outside of battles, it’s very much in the style of a text-based adventure game. When fights happen, the game switches to a simple, yet familiar, TRPG-style overhead view. This game was undoubtedly a major influence on the TRPG genre in Japan, and its presence may explain why Japanese players took so readily to Ultima in the following years.

Another possibility, albeit an outside one, is Koei’s Dragon and Princess, the very first RPG developed in Japan. This was released on NEC’s PC-8001 computer in 1982, and I’ve seen at least one source that says it came out in December of that year. That would likely put it after the release of Tunnels of Doom. It’s an interesting game. Outside of battles, it’s very much in the style of a text-based adventure game. When fights happen, the game switches to a simple, yet familiar, TRPG-style overhead view. This game was undoubtedly a major influence on the TRPG genre in Japan, and its presence may explain why Japanese players took so readily to Ultima in the following years.

Ultima 3

Speaking of Ultima, this is where it enters the picture. The first two Ultima games had players controlling a single character, but for 1983’s Ultima 3, creator Richard Garriott wanted to start allowing parties of heroes instead. Rather than continue with the first-person battles found in the first two Ultima games, Garriott chose to go with a separate battle screen that, you guessed it, had the party of heroes and the monsters arranged on a tile-based battlefield. Ultima 3 was a massive hit worldwide, and there’s little doubt it helped popularize this style of RPG combat. I think this satisfies our historical precedent, so I’m not going to bother going into detail about any further RPGs with TRPG-style combat. There were plenty in the following years, notably games like Wizard’s Crown and Pools of Radiance, but I don’t think they had much of an impact on the TRPG hybrid genre.

Speaking of Ultima, this is where it enters the picture. The first two Ultima games had players controlling a single character, but for 1983’s Ultima 3, creator Richard Garriott wanted to start allowing parties of heroes instead. Rather than continue with the first-person battles found in the first two Ultima games, Garriott chose to go with a separate battle screen that, you guessed it, had the party of heroes and the monsters arranged on a tile-based battlefield. Ultima 3 was a massive hit worldwide, and there’s little doubt it helped popularize this style of RPG combat. I think this satisfies our historical precedent, so I’m not going to bother going into detail about any further RPGs with TRPG-style combat. There were plenty in the following years, notably games like Wizard’s Crown and Pools of Radiance, but I don’t think they had much of an impact on the TRPG hybrid genre.

Bokosuka Wars

While RPGs with tactical combat and strategy games were both popular genres in the West in the 1980s, they rarely met in the TRPG form we think of today. There were some games that skirted awfully close, like Westwood’s BattleTech: The Crescent Hawk’s Inception, but the genre wouldn’t ignite in the West until much later. Japanese developers flirted with the genre throughout the 1980s, so it’s perhaps little surprise that they struck gold on the concept a couple of years sooner. Interestingly, two of the most frequently-cited inspirations for the genre from Japanese developers are real-time games with quite a few action elements. Koji Sumii’s Bokosuka Wars, released for the Sharp X1 in 1983, is an odd prototype of a real-time strategy game that sees you controlling a leader who has to gather an army and overthrow a castle. Imagine a castle defense game where you’re controlling the legion of terrible peons, and you’ve more or less got Bokosuka Wars.

While RPGs with tactical combat and strategy games were both popular genres in the West in the 1980s, they rarely met in the TRPG form we think of today. There were some games that skirted awfully close, like Westwood’s BattleTech: The Crescent Hawk’s Inception, but the genre wouldn’t ignite in the West until much later. Japanese developers flirted with the genre throughout the 1980s, so it’s perhaps little surprise that they struck gold on the concept a couple of years sooner. Interestingly, two of the most frequently-cited inspirations for the genre from Japanese developers are real-time games with quite a few action elements. Koji Sumii’s Bokosuka Wars, released for the Sharp X1 in 1983, is an odd prototype of a real-time strategy game that sees you controlling a leader who has to gather an army and overthrow a castle. Imagine a castle defense game where you’re controlling the legion of terrible peons, and you’ve more or less got Bokosuka Wars.

Silver Ghost

The other notable source of inspiration was 1988’s Silver Ghost for the PC88. Camelot Software Planning’s Hiroyuki Takahashi swears up and down that this game was what inspired him to create the 1992 SEGA Genesis game Shining Force. Silver Ghost is an action RPG where you often command large groups of characters, and honestly doesn’t have a whole lot of TRPG elements in it. I think it’s safe enough to call it another prototype of an RTS, and inspiration can certainly come from odd sources, but I continue to be skeptical that Takahashi’s game which closely resembled a competitor’s popular game on another platform had nothing to do with that game.

The other notable source of inspiration was 1988’s Silver Ghost for the PC88. Camelot Software Planning’s Hiroyuki Takahashi swears up and down that this game was what inspired him to create the 1992 SEGA Genesis game Shining Force. Silver Ghost is an action RPG where you often command large groups of characters, and honestly doesn’t have a whole lot of TRPG elements in it. I think it’s safe enough to call it another prototype of an RTS, and inspiration can certainly come from odd sources, but I continue to be skeptical that Takahashi’s game which closely resembled a competitor’s popular game on another platform had nothing to do with that game.

Tir-Na-Nog

There’s one more somewhat less-trumpeted game that I think merits mention here. Japanese publisher SystemSoft is known for their turn-based simulation games, with their most famous being the Daisenryaku series of military sims. In 1987, they released an Ultima 3-like RPG called Tir-Na-Nog on the NEC PC98. It’s only a hunch on my part, but I think this game may have somewhat influenced the creator of Fire Emblem, Shouzou Kaga. When he parted ways with Nintendo after Fire Emblem: Thracia 776 was completed in 1999, he started his own development studio. Its name was Tirnanog. Sure, he might just be a big fan of Celtic mythology (who isn’t?), but the timing certainly fits for this game to have at least planted a seed in Kaga’s mind. Again, this is simply my own speculation.

There’s one more somewhat less-trumpeted game that I think merits mention here. Japanese publisher SystemSoft is known for their turn-based simulation games, with their most famous being the Daisenryaku series of military sims. In 1987, they released an Ultima 3-like RPG called Tir-Na-Nog on the NEC PC98. It’s only a hunch on my part, but I think this game may have somewhat influenced the creator of Fire Emblem, Shouzou Kaga. When he parted ways with Nintendo after Fire Emblem: Thracia 776 was completed in 1999, he started his own development studio. Its name was Tirnanog. Sure, he might just be a big fan of Celtic mythology (who isn’t?), but the timing certainly fits for this game to have at least planted a seed in Kaga’s mind. Again, this is simply my own speculation.

Fire Emblem

Speaking of Fire Emblem, that’s about where we are. Fire Emblem is to the Japanese TRPG what Dragon Quest is to the JRPG. It might not have been the first in the abstract sense, but it popularized the familiar foundations that persist in the genre to this day. After the success of their first original title Famicom Wars (the first in a series known in the West as Advance Wars), developer Intelligent Systems was looking to get away from the concept of modern warfare and try something more fantastical. One of the members of the team, Shouzou Kaga, came up with the idea of Fire Emblem as a way of marrying the idea of story-telling with the simulation/strategy genre. He wanted players to really care about their units, and thought the best way to accomplish that was to name them and get players to invest time and energy into building them up. From a mechanical standpoint, it’s not hard to see how Intelligent Systems got to Fire Emblem from Famicom Wars.

Speaking of Fire Emblem, that’s about where we are. Fire Emblem is to the Japanese TRPG what Dragon Quest is to the JRPG. It might not have been the first in the abstract sense, but it popularized the familiar foundations that persist in the genre to this day. After the success of their first original title Famicom Wars (the first in a series known in the West as Advance Wars), developer Intelligent Systems was looking to get away from the concept of modern warfare and try something more fantastical. One of the members of the team, Shouzou Kaga, came up with the idea of Fire Emblem as a way of marrying the idea of story-telling with the simulation/strategy genre. He wanted players to really care about their units, and thought the best way to accomplish that was to name them and get players to invest time and energy into building them up. From a mechanical standpoint, it’s not hard to see how Intelligent Systems got to Fire Emblem from Famicom Wars.

I suppose this is as good of a cut-off point as any for now. Check back for next week’s Reload as I run through what happened in the Western gaming scene to kick off the TRPG genre and some of the bigger games that followed in both styles. Don’t forget to swing by the forums and join in on the RPG Reload Play-Along of QuestLord if you’re looking for some fun adventures. We’ve still got half the month left, which is plenty of time to get it done. As for me, I’ll be back next week to bury you with more words. Thanks for reading!

Next Week’s Reload: The History of TRPGs Part 2