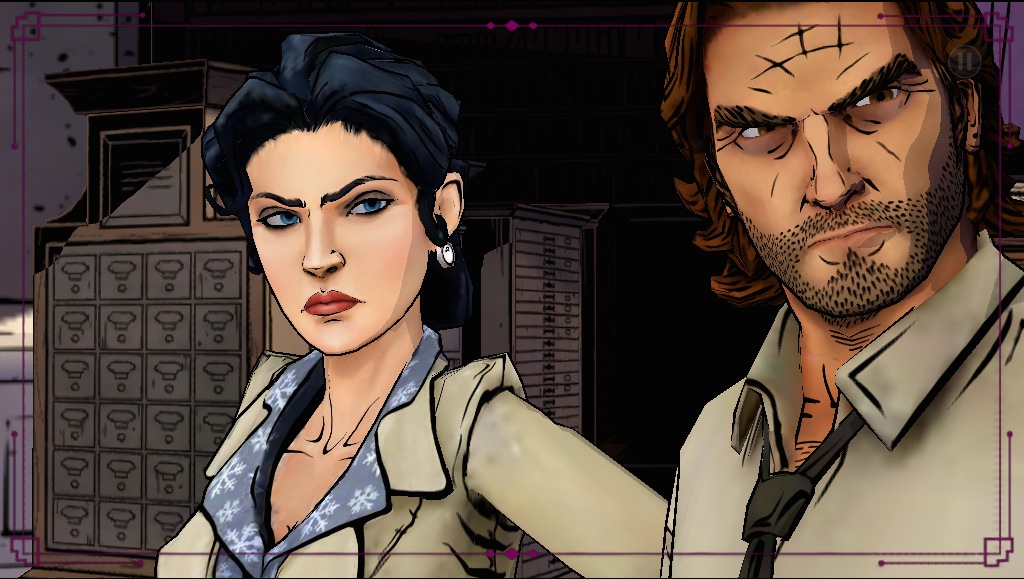

The first thing that happens in Telltale Games’ The Wolf Among Us (Free) is that Sheriff Bigby Wolf talks to a toad in a cardigan. The second thing, at least for me, was that he gets beaten to death (twice). Apparent cause of death is an axe handle through the eye socket, but I’m no doctor. That’s a hell of a first impression for the series, adapted from Bill Willingham’s Fables franchise. Fables’ premise—that fairytale characters have come to live in the real-world Bronx—isn’t uncommon: The 10th Kingdom and Neil Gaiman’s American Gods both predate Willingham, and contemporary shows like Once Upon A Time and Sleepy Hollow continue the unevenly handled tradition.

The first thing that happens in Telltale Games’ The Wolf Among Us (Free) is that Sheriff Bigby Wolf talks to a toad in a cardigan. The second thing, at least for me, was that he gets beaten to death (twice). Apparent cause of death is an axe handle through the eye socket, but I’m no doctor. That’s a hell of a first impression for the series, adapted from Bill Willingham’s Fables franchise. Fables’ premise—that fairytale characters have come to live in the real-world Bronx—isn’t uncommon: The 10th Kingdom and Neil Gaiman’s American Gods both predate Willingham, and contemporary shows like Once Upon A Time and Sleepy Hollow continue the unevenly handled tradition.

The violence in this introduction stands out as a way to overcompensate for The Wolf Among Us’ inherent silliness, to convince us that it’s brutal and dark. The overwhelmingly grisly murder that sets the game in motion only reinforces that idea.

The bloody posturing is unnecessary, as the The Wolf Among Us has enough grit and texture to stand on its own without drawn-out fight scenes or swear words. The game draws its tension and mood from Fabletown’s deep violets and navy blues, from a dusky soundtrack, from punchy voice-acting. The racism and classism that undergird the world of Fables are both sadder and more desperate than the blood and broken bones Telltale chooses to highlight first.

Still, Telltale are remarkably efficient alchemists when it comes to Willingham’s setting. They have an ear for dialogue and a genuine knack for plotting and pacing, but the promise of exploring more of the beautifully realized Fabletown is compelling too. Bigby’s melodrama aside, The Wolf Among Us would still be interesting as a political parable, and if there’s one criticism, it’s that Telltale keeps the reigns too tight and doesn’t offer enough chances to poke at the seams of Fabletown.

Adventure games usually handle cop stories well: You talk to people, gather clues, and make connections. Bigby does those things in The Wolf Among Us, too, but they don’t culminate in some solved puzzle as much as they change the tone and texture of Bigby’s relationships with other characters.

In other words, this is a narrative experience, and the game’s whodunit is a plot device, not a game mechanic. Collecting evidence may unlock new dialog options, but its main purpose is to deepen the game’s mystery and to force Bigby to make decisions. That said, the choices players make over the course of The Wolf Among Us—some small, some large—form the game’s backbone, and every interaction seems to tie into Telltale’s narrative Rubik’s Cube.

Unfortunately, performance problems on older devices like the iPad 2 crop up with regularity. Stuttering frame rates and delayed inputs make for shambolic action scenes and disrupted cinematics, and The Wolf Among Us suffers from general instability and locks up often. These technical problems are a black spot on an otherwise gorgeous game, especially since it depends on smart camera work and pacing to sustain its story.

Episode 1 — Faith

Early in this episode, Sheriff Bigby explains to Colin that he keeps the peace in Fabletown “by being big, and being bad.” It’s on the nose, but Colin’s response cuts to the heart of The Wolf Among Us: “Don’t say that shit in front of people. It’s embarrassing.”

Colin is decrying Bigby’s chest-thumping, but it’s a nice reminder that the characters in Fabletown have pre-conceived notions about Bigby, that those notions can change based on player input, and the this is primarily a game about exploring relationships in a fairytale society.

“Faith”’s strongest scene occurs in a library, where routine bureaucracy comes face-to-face with fairytale magical fantasy. There are signs of “real” life—a deputy mayor, an administrator, public health and birth records—juxtaposed with a magic lamp and an omniscient talking mirror. It’s just enough to remind of you of Fables’ allegorical potential while still breathing life into a mysterious new environment.

Like in Telltale’s previous series, The Wolf Among Us “remembers” certain choices and uses them to shape the story to come. This is an increasingly common narrative trick, but I’m skeptical of games that notify the player so obviously when it happens. Granted, “Faith” is only the first of five episodes, so it’s hard to see if and how Bigby’s kindness toward, say, Bufkin will play out. What’s clearer already is that Bigby’s character, his relationships, and “Faith”’s plot points are highly malleable.

The Wolf Among Us’ surveillance seems like it would extend to the quick-time events that govern its fights. Bigby’s potential for ultraviolence rears its head more than once in “Faith,” and his restraint—or lack thereof—should have narrative repercussions. It doesn’t.

The QTEs themselves are straightforward taps, flicks, and swipes. One pleasant surprise is how flexible they are: you can miss a few prompts without failing, and the fights are choreographed well enough that everything flows naturally, even when a punch or headbutt is flubbed or skipped on purpose.

Here’s the rub: it’s not always clear what a given QTE will do, or which ones can be skipped without losing the fight. This has an unfortunate chilling effect on roleplaying. In one early fight, Bigby steals an axe while a QTE prompt hovers near his opponent’s neck. Thinking his next move would be to decapitate someone, I skipped it and failed the fight. I was punished for playing Bigby less violently than Telltale intended.

Turns out, Bigby merely breaks the guy’s jaw, but that’s beside the point. When Bigby talks to people, Telltale encourages us to roleplay, to make decisions that have lasting consequences; when he’s fighting someone, we get bottlenecked along a narrow path.

Almost every game mechanic in “Faith” builds upon, changes, or informs some aspect of the narrative. With one enormous, climactic exception, the fight scenes in “Faith” don’t. Our choices in “Faith” matter in one context but not the other, and that’s jarring.

Nevertheless, “Faith” puts forward a dense tale that excels at building momentum. Here’s to sustainability.

Episode 2 — Smoke & Mirrors

The two-month gap between “Faith” and “Smoke & Mirrors” is felt right away: the finer plot points get lost in the shuffle of new characters, and “Smoke” struggles to find a rhythm as players try to remember who’s who and why they’re interrogating the Woodsman.

“Smoke” eventually settles into itself, but it’s a much shorter episode than “Faith.” Its brevity is compounded by the way Telltale shunts us from one scene to the next. For example, Bigby examines a headless torso early in the episode. There are several clues and interaction points to explore, but one in particular triggers Deputy Mayor Ichabod Crane to swoop in like hideous bird to shoo Bigby out of the room.

You won’t get another crack at the body, even if there are other clues to gather, and the implication is clear: moving the story forward is more important than investigating. It’s frustrating that “Smoke” curtails a chance to do something both the character and mechanics are ostensibly suited for, especially since the investigation in Toad’s apartment worked so well in “Faith.”

That same pressure to move quickly exerts itself through the timed dialogue system that Telltale has been using since The Walking Dead. This design makes sense in the context of a zombie apocalypse, but this episode never earns the sense of urgency imposed onto it.

Where “Faith” is violent, “Smoke” is seedy, taking Bigby through a strip club, brothel, and flop hotel in short order. It’s unclear if this slum tourism supports a good faith effort to explore the social ills at the foundation of the Fables series, but Bigby seems poised to act as the blunt force needed to clear a path for much-needed reforms. By that same token, there’s an undercurrent of class guilt and noblesse oblige in the episode’s most lurid scenes.

That doesn’t keep the scene between Bigby and Holly from being the best in the episode. Not only does it encapsulate the game’s class tension, but it also delivers on Telltale’s promise of a reactive and responsive gameworld. Holly and Grendel both appreciate that I-as-Bigby decided against ripping Grendel’s arm off. Indeed, the relationship between the player, Bigby, and the other denizens of Fabletown continues to be a highlight of The Wolf Among Us.

More violent interactions are subtler, too. In the opening scene of “Faith,” Bigby is forced to pummel the Woodsman, whether the player wants to or not. Near the end of “Smoke & Mirrors,” Bigby again finds himself in a brawl. This fight scene is more flexible, however, and we’re allowed to lay off if need be. Bigby’s restraint doesn’t go unnoticed, thankfully.

Still, “Smoke & Mirrors” is more often interesting than riveting, consigned to doing The Wolf Among Us’ dirty work: it moves the plot forward in ways that are necessary but not compelling, and touches on the series themes without revealing its hand too early. It’s a short, workmanlike episode, content to stand on “Faith”’s back and prep us for what’s next.

Episode 3 — A Crooked Mile

By episode three, The Wolf Among Us has settled into a familiar rhythm: Bigby talks to people, makes choices, conducts investigations, and occasionally gets stabbed, pummeled, or shot. The game’s design is well established, and episode three displays the best and the worst of what The Wolf Among Us has to offer.

Bigby and Snow spend most of “A Crooked Mile” tracking the birdlike Ichabod Crane. We learn, for example, that he regularly and intentionally neglects and ignores his poorest constituents, giving us insight into both his character and those found at the Trip Trap. Maybe Holly, Grenn, and the Woodsman are sullen, violent, suspicious, and anti-authoritarian because they’re constantly let down by an ineffectual and unsympathetic government.

(Snow seems more compassionate, but even she comes down surprisingly hard on Aunty Greenleaf’s cottage glamour industry, War on Drugs style.)

Those downtrodden characters soften if Bigby is nice to them but only become rougher around the edges when he’s not. On the one hand, it’s great that Bigby’s interactions and relationships are interesting, persistent, and reactive; on the other, The Wolf Among Us’ social, racial, and economic subtext is sometimes a mere reflecting pool. Wherever you-as-Bigby falls along these political fault lines, The Wolf Among Us is too happy to spit out the attitudes you’ve already put into it.

Meanwhile, “Mile”’s structure is the most complex yet, giving Bigby a handful of diverging routes before shuttling him toward a climactic finish. Each new choice has a compound effect, and this episode does a good job of giving each player a somewhat personalized experience. For example, my choices led me to the ever-sinister Bluebeard and Fly Catcher, the Tweedles’ dopey janitor, but I missed out on a great scene with Jack Horner.

The flipside is not all possible routes through “A Crooked Mile” are equally fun or informative. My last stop, for example, was at the Tweedle’s office, where I picked through one file cabinet before being herded to the next part of the game. Because I just happened to pick the right (or wrong) interaction point, I missed out on an entire room’s worth of info, and the big reveal of the series’ shadowy villains fell flat as a result.

The Wolf Among Us’ fast pace and trigger-happy checkpointing system were an annoyance in the first two episodes, but in “A Crooked Mile,” they make the writing, plotting, and pacing feel sloppy. Telltale have built a cool world, a great noir mystery, and characters I’ve grown to like, but they’re sometimes betrayed by a gameplay pipeline that feels restrictive and exacting.

Still, “A Crooked Mile” starts off incredibly strong, with a plot that moves forward and spends extra time on the series best characters. And while the climax is a bit uneven, it pulls enough weight that I immediately regretted my final decision. If nothing else, “A Crooked Mile” is the densest and most intriguing episode to date, a fine midpoint before what is shaping up to be a tumultuous conclusion.

Episode 4 — In Sheep’s Clothing

“In Sheep’s Clothing” is all about the recently (and somewhat awkwardly) revealed kingpin at the heart of Fabeltown’s underworld. Bigby explores the Crooked Man’s various criminal enterprises, but we don’t learn much that we couldn’t have guessed—it’s not a big stretch to guess that a vicious, murderous loan shark would also dabble in trafficking, prostitution, racketeering, and extortion.

This episode may not hold too many surprises, but it doubles down on the series’ thematic core in a way that makes Bigby’s inevitable tête-à-tête with the Crooked Man incredibly satisfying.

The large-scale conflict between Fabletown’s government and the Crooked Man’s mafia plays out through the game’s minor characters. Without a place in society, people like Jack Horner, (Tiny) Tim, and Aunty Greenleaf find a home in the Crooked Man’s abandoned church. Meanwhile, Fables like Colin and Toad remain skeptical and resentful of the government, even if they haven’t resorted to crime yet.

Meanwhile, Snow’s assertive, authoritarian streak that began in Aunty Greenleaf’s apartment continues during a showdown with Colin. After being proverbially stuffed into a fridge in the first episode, it’s nice to see Snow come into her own and exert some agency, even if I don’t necessarily care for her new hardline politics. Her change from a white outfit into dark grey isn’t just a matter of fashion, either. (I do wish she hadn’t accused me-as-Bigby of excessive violence, though—I haven’t dismembered or killed anybody yet!)

Later, Bigby asks the un-glamoured Toad why it’s “so hard to just follow the rules,” and the answer is that Bluebeard and Crane have rigged the game against him. “It’s getting hard to tell the difference between the Business Office and Fables like the Crooked Man,” Toad replies, cutting to the heart of the matter.

Bigby, of course, is at the center of these rising tensions, and his moral authority as a dispenser of justice and keeper of the peace is slipping. This is especially clear at the end of the episode, when Tim points out that Bigby, in his role as Sheriff, is complicit in creating a situation in Fabletown that allowed a criminal like the Crooked Man to become so powerful in the first place.

That makes for tense, terse writing as it is, but Telltale’s games live and die by forcing players to make interesting decisions. Nothing in “A Sheep’s Clothing” comes to a head, but it’s clear that Bigby will soon have to choose between Snow and Colin, between doing what’s right and doing what he can, between enforcing the law and trying to make Fabletown a better place.

In short, the writing in “In Sheep’s Clothing” serves the game’s most interesting decisions, and The Wolf Among Us’ mechanics illuminate and inform this episodes’ themes and dynamics. Despite being a relatively straightforward episode—there’s one standard fight scene, one minor branching path, and lots of exposition—the link between the writing, the mechanics, and Bigby’s last decision make “In Sheep’s Clothing” the richest episode to date.

Episode 5 — Cry Wolf

“Cry Wolf,” The Wolf Among Us’ finale, has a problem: it’s an entire episode of denouement, tasked with wrapping up loose ends and answering outstanding questions, usually through exposition. The main mystery driving the series—who brutally decapitated Faith and Lily?—was solved in “A Crooked Mile,” three real-time months ago. Any new information, while interesting, is tied to action that takes place before the events of “Faith.”

That doesn’t keep Vivian and Georgie Porgie’s final scene from being the strongest in the episode and one of the best in the series. In it, Georgie details the Crooked Man’s machinations and puts his life in sharp relief against Bigby’s. In a series about decisions and their consequences, Georgie’s admission that he “had no choice” hits home. Georgie’s foul-mouthed swan song encapsulates all of the tensions and conflicts The Wolf Among Us has tried to explore during its run and in the process allows a violent pimp and his exploitative madame to cut tragic, sympathetic figures.

The newly liberated Nerissa, like Georgie before her, spends most of her last scene ruminating on the past before offering Bigby an ambiguous farewell. Ambiguity can be a useful storytelling technique, but here it only leads to thematic inconsistency and kludgy, awkward plotting. Nerissa’s revelation doesn’t stand up to scrutiny, but it’s the one moment in “Cry Wolf” that surges forward instead of looking back. For fans of the series, the energy generated by a well-placed tease for an inevitable Season Two gives this episode a boost.

Nestled between Georgie’s catharsis and Nerissa’s masterstroke is the Crooked Man’s ad hoc trial, which should have been the apex of the episode. It’s not, mostly because the Crooked Man isn’t interesting enough to support “Cry Wolf”’s biggest set piece on his own. His introduction as a primary antagonist comes too late, and his motives are bland and his decisions opaque as a result.

Worse, he’s predictable. His ideology and self-defense would have been easily forecast in any case, but they were also pre-empted, subtly and poignantly, by Tiny Tim at the end of “In Sheep’s Clothing” and Georgie Porgie in the previous scene. At some point, The Wolf Among Us shifted from gritty noir mystery to police procedural, and everyone already knows how Law & Order usually ends.

The courtroom scene had a secondary goal, too: to bring Fabletown regulars together to show Bigby how his actions have affected the town. My save file actually treats Bigby as if he elected to burn Auntie Greenleaf’s Glamour Tree down (I didn’t). This is a small bug, but it undermines the game’s raison d’être—a reactive, internally consistent world is one of the foundational elements of The Wolf Among Us’ narrative design.

My own little Auntie Greenleaf glitch didn’t change the way “Cry Wolf” ends, and, most likely, neither did any of Bigby’s other decisions. Bigby’s choices were never going to have a huge effect on Fabletown—these games have limits—but it’s enough to have made them.