There’s a great story — perhaps apocryphal — about Will Wright designing SimCity to reflect his political beliefs. Specifically, the thinking is that Wright designed the trains and buses in that game to run smoothly and efficiently to reflect his own views about the importance of public transportation. I’m not sure how true that is, but it’s a great illustration that the games we play — and how we play them — says something about us.

There’s a great story — perhaps apocryphal — about Will Wright designing SimCity to reflect his political beliefs. Specifically, the thinking is that Wright designed the trains and buses in that game to run smoothly and efficiently to reflect his own views about the importance of public transportation. I’m not sure how true that is, but it’s a great illustration that the games we play — and how we play them — says something about us.

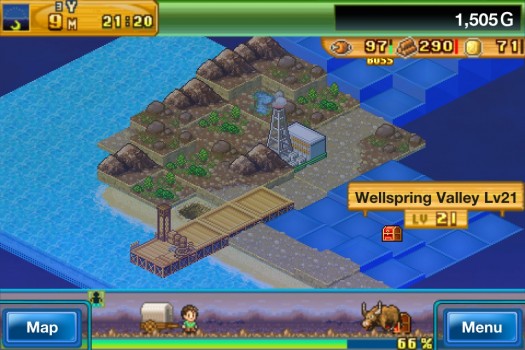

Kairosoft’s latest, lightweight city management sim Beastie Bay (Free), for example, let me build my own kind of environmentalist utopia. Sure, I could probably attract more tourists (and therefore more money) by building roads through my island, but I’d rather have the beaches and wooded hills and caves — and the fish, bears, and mecha-chimpanzees that live in them. I have plenty of food and lumber — resources you’ll need for everything from researching electricity to building nests to upgrading weapons — and my upkeep costs are low enough that I’m not forced to expand faster than I want to. I appreciate that Beastie Bay is flexible enough to allow me that freedom.

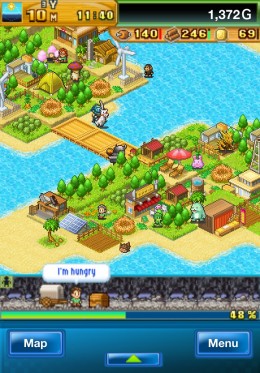

In any case, the premise of Beastie Bay is straightforward in a weird, videogame-logic kind of way: a man named Robin washes up on the deserted Sunny Isle with his assistant and his pet duck (or dog, if that’s the starting ally you’d rather have). Robin and his duck explore the island, rescue some locals, and start building houses. Robin can “tame" the local wildlife, who serve the dual purpose of fighting the feral animals living on the island and harvesting its natural resources. It’s basically Pokémon and Tropico smushed up together.

In any case, the premise of Beastie Bay is straightforward in a weird, videogame-logic kind of way: a man named Robin washes up on the deserted Sunny Isle with his assistant and his pet duck (or dog, if that’s the starting ally you’d rather have). Robin and his duck explore the island, rescue some locals, and start building houses. Robin can “tame" the local wildlife, who serve the dual purpose of fighting the feral animals living on the island and harvesting its natural resources. It’s basically Pokémon and Tropico smushed up together.

So the game is split into two halves: the island management section — the game keeps calling it a “resort," but like I said, I did my best to keep it rustic — and the exploration and combat section. The two combine to make a nice little feedback loop: while exploring, you’ll tame more allies, who will in turn help harvest your resources, which allow you to expand your island and strengthen your equipment. It’s a tidy little dynamic and should feel familiar to long-time Kairosoft fans.

It’s worth nothing, though, the Beastie Bay is relatively opaque with its higher order mechanics — it took a lot of experimenting to figure out how to upgrade my buildings, for example. I still can’t figure out why I’m not allowed to build any more hotels for the unending legion of tourists washing up on my docks. Sometimes, useful mechanics or items are just blocked off weirdly and will become unlocked after players clear a certain dungeon or rescue a certain townsperson. Beastie Bay isn’t really a hard game, but there are a lot of moving parts, and newcomers will need to do a bit of tinkering to get a feel for it.

The simulation aspect of the game is particularly engaging, though. There are always new areas to develop and — thanks to a “destroy" command — re-develop as you start to master the game’s mechanics. All of the different units, resources, and facilities work together based on proximity: allies can only gather fruit and lumber near their nests; generators can only send electricity a few blocks; and only students living near the fighting school can enroll. As you gain more land, you’ll start zoning things off so that no resource is wasted. Your island will likely start to plateau after a few hours, but after you break through it, Beastie Bay is almost infinitely customizable, depending on your goals and interests.

Beastie Bay‘s combat, however, doesn’t fare quite as well. It uses a pretty rudimentary rock-paper-scissors structure, and players have access to basic attacks, special skills, and items. It’s basic stuff, with an extra party-switching mechanic mixed in for good measure: you’ll lead in with a main, three-ally party, with another three in reserve. The idea is build a well-rounded group and switch in and out as necessary.

The problem is that Beastie Bay‘s combat hews a little to closely to its obvious Pokémon inspiration: switching party members or using an item takes up the party’s entire turn. Most party-based role-playing games let each team-member use an item without ruining the whole round. It’s a minor thing, really, but Beastie Bay has some jagged difficulty spikes and an absolutely ruthless AI: Unigorillas, for example, have an almost preternatural ability to target my healers before wiping out the rest of my party.

Dungeon crawling in Beastie Bay is mostly just a tool for taming more allies to work the island, and for unlocking new research and facility types to use in the more engaging sim portions of the game, but Kairosoft made it harder than it needs to be.

Dungeon crawling in Beastie Bay is mostly just a tool for taming more allies to work the island, and for unlocking new research and facility types to use in the more engaging sim portions of the game, but Kairosoft made it harder than it needs to be.

Difficulty annoyances aside, Beastie Bay‘s combat dovetails nicely with a surprisingly broad collection of micro-systems and economies: weapons can be crafted and upgraded; investing in neighboring countries will lead to better wares in your own shops; allies are ranked based on raw power and potential growth, and can be trained in repeatable dungeons or a training school; the list goes on. None of these mechanics are particularly deep individually, but they combine to make Beastie Bay an engaging sim that focuses more on breezy self-expression and self-improvement than meeting arbitrary challenges or being the first to land on the moon.

A note on in-app purchases: the free, ad-supported version of Beastie Bay is robust and enjoyable and, as far as I can tell, in no way different than the paid version. $4.99 strips the game of advertisements and lets players use their iDevice’s landscape mode. Landscape mode is, admittedly, the superior way to play Beastie Bay, but there’s an inordinate amount of well-designed, well-executed fun to be had for free.

Now, if you’ll excuse me, Sunny Isle needs a museum and some more beach chairs.