![]() Brace yourselves, we’re going to talk about some truly old-school gaming in this review. Before there was Clash Of Clans (Free), Call Of Duty, Tetris ($1.99), Super Mario Bros., or even Pong, a huge gaming craze swept the world. It was a puzzle game known to the western world as Tangrams, brought over in the early 19th century from China, where it had been around for several hundred years. Suddenly those months-long New Zealand soft launches don’t look so bad, do they? If you aren’t familiar with Tangrams, the puzzle involves using seven pieces to try to match a set shape. You would think this to be a pretty shallow affair, but there have been several thousand different puzzles made. I’m not sure if it’s still the case, but books of Tangram puzzles were always a mainstay in gas stations and convenience stores when I was a kid.

Brace yourselves, we’re going to talk about some truly old-school gaming in this review. Before there was Clash Of Clans (Free), Call Of Duty, Tetris ($1.99), Super Mario Bros., or even Pong, a huge gaming craze swept the world. It was a puzzle game known to the western world as Tangrams, brought over in the early 19th century from China, where it had been around for several hundred years. Suddenly those months-long New Zealand soft launches don’t look so bad, do they? If you aren’t familiar with Tangrams, the puzzle involves using seven pieces to try to match a set shape. You would think this to be a pretty shallow affair, but there have been several thousand different puzzles made. I’m not sure if it’s still the case, but books of Tangram puzzles were always a mainstay in gas stations and convenience stores when I was a kid.

One of the strengths of the game is that it frequently allows for multiple solutions to the same problem, allowing the player a certain personal satisfaction in finding the answer that works for them rather than the one true strategy. Of course, many people accidentally or deliberately stumble into what I call the Ikea problem, where you have your finished object but still have a piece left over. In doing a little research, this is related to a concept called the Tangram Paradox, where arranging the same set of pieces in slightly different ways can result in a shape with apparently smaller physical dimensions. To an extent, this is the concept that Zengrams ($1.99), the new release from Third Eye Crime ($1.99) developer Gameblyr, plays with to give itself a new spin on an ancient game.

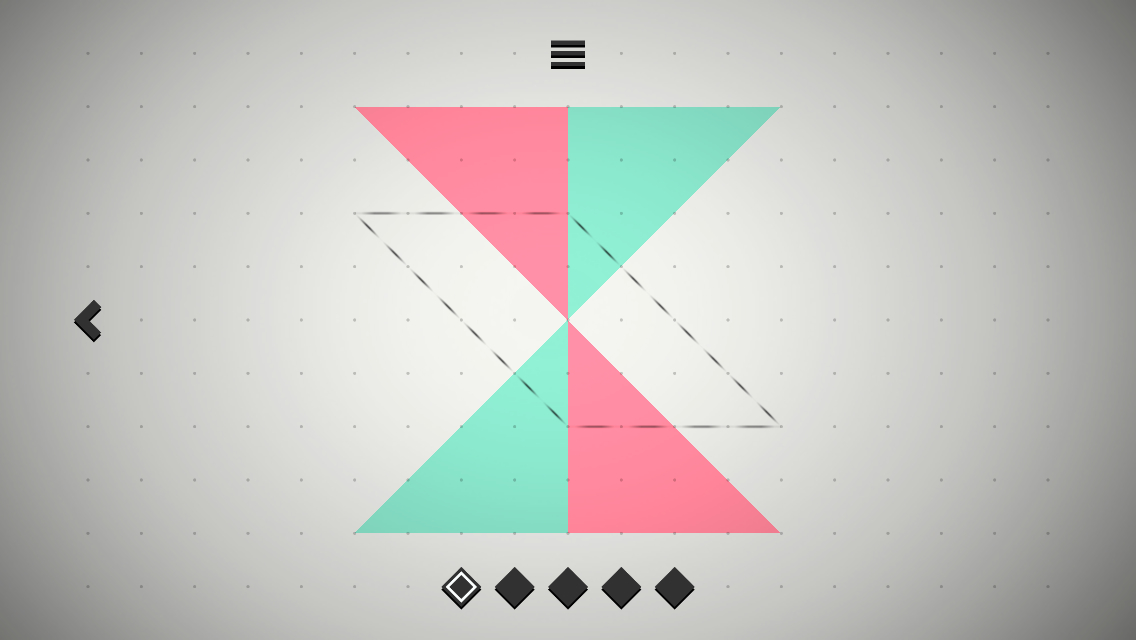

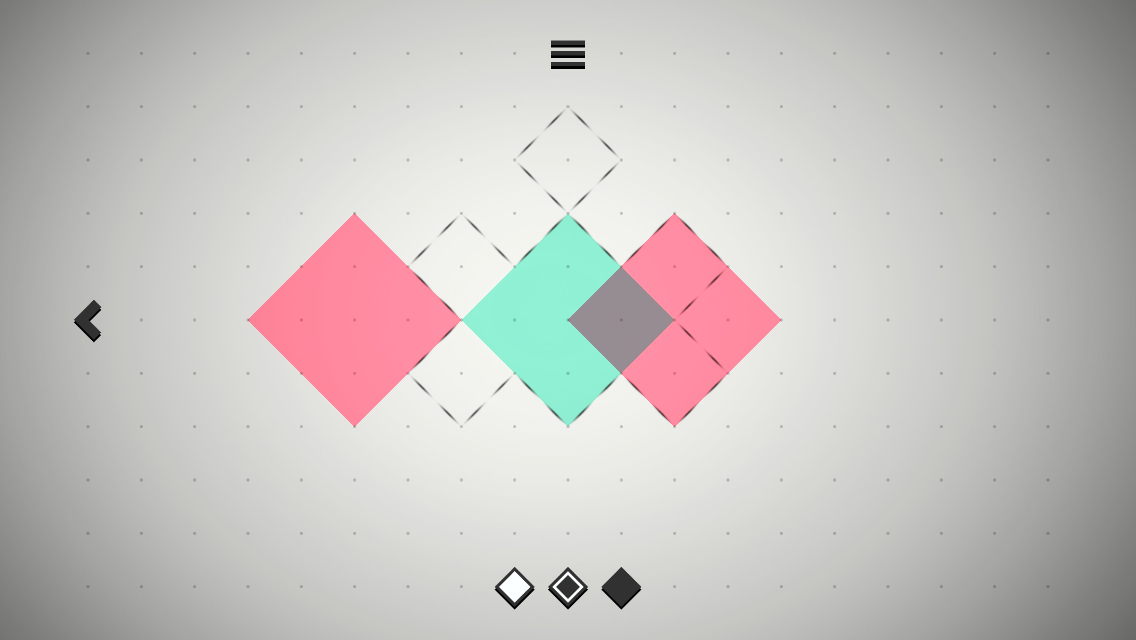

Zengrams has the same basic idea as Tangrams. On each stage, you are given a specific set of pieces and need to use all of them to fill a shape. Unlike the traditional game, you can’t rotate these pieces, but in lieu of that, you are given an interesting new ability, and one really only possible in electronic form. The pieces can come in different colors, and various things can happen when they come in contact with each other. If two pieces are the same color and touch one another, they become one piece. If they overlap, the colors will combine to create a new color and a new piece that can be moved independently of its parents. Typically, the pieces you are given at the start of a stage are far too big to fit in the target shape, so you’ll almost always have to make use of this ability in order to solve the puzzle at hand. Adding extra challenge, and perhaps a guiding light to the clever, you’re given a limited number of moves in which to clear the stage.

It seems like a simple gameplay variation, but it allows for some fresh, challenging puzzles that should please newcomers and Tangram veterans alike. The game contains 70 stages, with the first 20 or so acting as something of a tutorial, though perhaps a slightly more challenging one than people may be accustomed to. After it shows you the basic tricks, the gloves come off, with some of these puzzles proving to be real stumpers. The best hint you have is that little counter at the bottom that shows how many moves you need to clear the stage with. It’s a firm reminder that no matter how complex the puzzle seems to be, clearing it really involves no more than a handful of correct steps. Finding those steps can be a whole other matter, but it at least keeps your brain from going too wild thinking about solutions.

One cool thing is that like the game that inspired it, there are often multiple solutions to the puzzles found in Zengrams. There are even a couple of stages where you can solve the puzzle in fewer moves than you’re given. It was very satisfying to talk to someone else playing the game and find we went about beating stages in different ways. It made me feel like I was awfully smart and creative, which is a nice feeling, however illusory it might be. It’s not all ego-fluffing, however. The puzzles are laid out one after another, and there’s no moving on until you figure out the puzzle in front of you. There were more than a few times where I got completely stuck and had to ask someone else, with their strategies often short and simple enough that I felt awfully stupid and oblivious for not finding them myself.

The good point of this structure is that it forces you to chew on a problem until you’ve found the answer rather than just passing it by. The bad point is that you can’t play another new stage until you’ve figured out the one you’re on, no matter how long that takes. I could easily see people walking away from Zengrams as a result of this set-up. It fits with the overall minimalistic vibe the game is going for, I suppose, avoiding gaudy level select screens and star ratings for unlocking stages. Immediately upon starting the game, you need only tap once to be taken to whichever stage you’re currently working on. If you want to go back and play a previous stage, you can shuffle back one-by-one. The visuals are simple and clear, and the music is soothing and unobtrusive.

I found Zengrams to be a satisfying puzzle game, albeit sometimes a very frustrating one. It worked better for me as something I would play for a few minutes and then put away for a while so that I could come back to it with a fresh brain, but each and every victory was a sweet one. The amount of content is quite substantial, and the difficulty curve was just steep enough to keep me progressing without letting me push through too easily. I haven’t finished all of the puzzles yet, but I can’t imagine giving up on the game until I do. If you enjoy logic puzzles, Zengrams is assuredly worth your time and money.