Every era of gaming has one or two genres that dominate. Eventually, the popularity of said genres give way to something new, and from there it’s a coin toss as to how relevant they remain. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, one of those “it" genres was the beat-em-up. In many ways defined by 1986’s Renegade, the genre became a worldwide sensation with the game’s spiritual successor Double Dragon. The game was a huge hit in the arcades, and its many home ports were tremendously popular. There was a Double Dragon comic, a Double Dragon cartoon, a Double Dragon toyline, and eventually even a Double Dragon live-action movie. Innumerable clones from virtually every other game publisher followed, flooding arcades and eventually the 16-bit home consoles until the coming of one-on-one fighting games pulled the market in another direction.

Every era of gaming has one or two genres that dominate. Eventually, the popularity of said genres give way to something new, and from there it’s a coin toss as to how relevant they remain. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, one of those “it" genres was the beat-em-up. In many ways defined by 1986’s Renegade, the genre became a worldwide sensation with the game’s spiritual successor Double Dragon. The game was a huge hit in the arcades, and its many home ports were tremendously popular. There was a Double Dragon comic, a Double Dragon cartoon, a Double Dragon toyline, and eventually even a Double Dragon live-action movie. Innumerable clones from virtually every other game publisher followed, flooding arcades and eventually the 16-bit home consoles until the coming of one-on-one fighting games pulled the market in another direction.

In all but the technical sense, however, Double Dragon lost its relevance well before the genre it popularized did. The game’s publisher, Technos Japan, knew they had a major hit on their hands and didn’t seem to know what to do with it. They rushed a couple of arcade sequels that drew increasingly little attention from players, and put together a couple of NES versions of said sequels that went in their own directions. The second NES game, Double Dragon 2, was fairly popular, but by the time Double Dragon 3 hit the NES in 1991 the writing appeared to be on the wall. Competition from the likes of Capcom’s Final Fight and SEGA’s Golden Axe had wrested the ball away from the poorly-managed Double Dragon series and the beat-em-up era of the franchise came to a close with the (again) rushed, somewhat tepid 1992 release Super Double Dragon on the Super NES.

The beat-em-up genre only had a couple more strong years ahead of it. Street Fighter 2 had released in 1991, and by and large gamers had turned their interest in co-op head-bashing into the competitive sort. Technos wouldn’t last much longer; the company folded in 1996 after failing to find much success in the 16-bit era of consoles. It wasn’t the end for Double Dragon, of course. A successor company named Million Corp was formed by ex-Technos staff and promptly scooped up the defunct company’s IP, including both Double Dragon and the Kunio-kun/River City brands that had once held such weight. Million wasn’t shy about licensing out the brands and collaborating with various third parties on new projects, so the series still popped up now and then. It was, however, the end of series creator Yoshihisa Kishimoto’s direct involvement with the games. He was sometimes brought in as a consultant, but he never got a chance to make another sequel to his own specifications.

Well, if you wait long enough, just about everything comes around again. Publisher Arc System Works acquired the Technos IP from Million in 2015 and got to work on reviving their most valuable brand: Kunio-kun/River City. But they didn’t forget Double Dragon. In the spirit of other retro throwbacks such as Mega Man 9 and New Super Mario Bros., Arc got in touch with many of the original Double Dragon team members to create a brand-new game that was decidedly old-school. Double Dragon 4 (Free) was announced out of the blue in late December of 2016, with a release on PlayStation 4 and Windows coming just one month later. In September of 2017 the game came to the Nintendo Switch with little fanfare, and it has now arrived on iOS with equally little warning.

On the one hand, it’s kind of amazing to get a new Double Dragon game from the original director, artist, composer, and programmer of the original games. But that’s precisely what separates Double Dragon 4 from other retro revivals, and may well be why it’s so very underwhelming. Most of these creators vanished into the shadows after Technos went bust, and while I doubt they stopped working in the industry entirely, you get the sense that they’re picking up not too far from where they left off. In Double Dragon‘s case, that’s not really a good thing. Remember, this is a once white-hot brand that prematurely died off because it fell behind its competition to a staggering extent. And indeed, Double Dragon 4 is full of the same kind of evolutionary dead-ends that hurt the series back in the 90s.

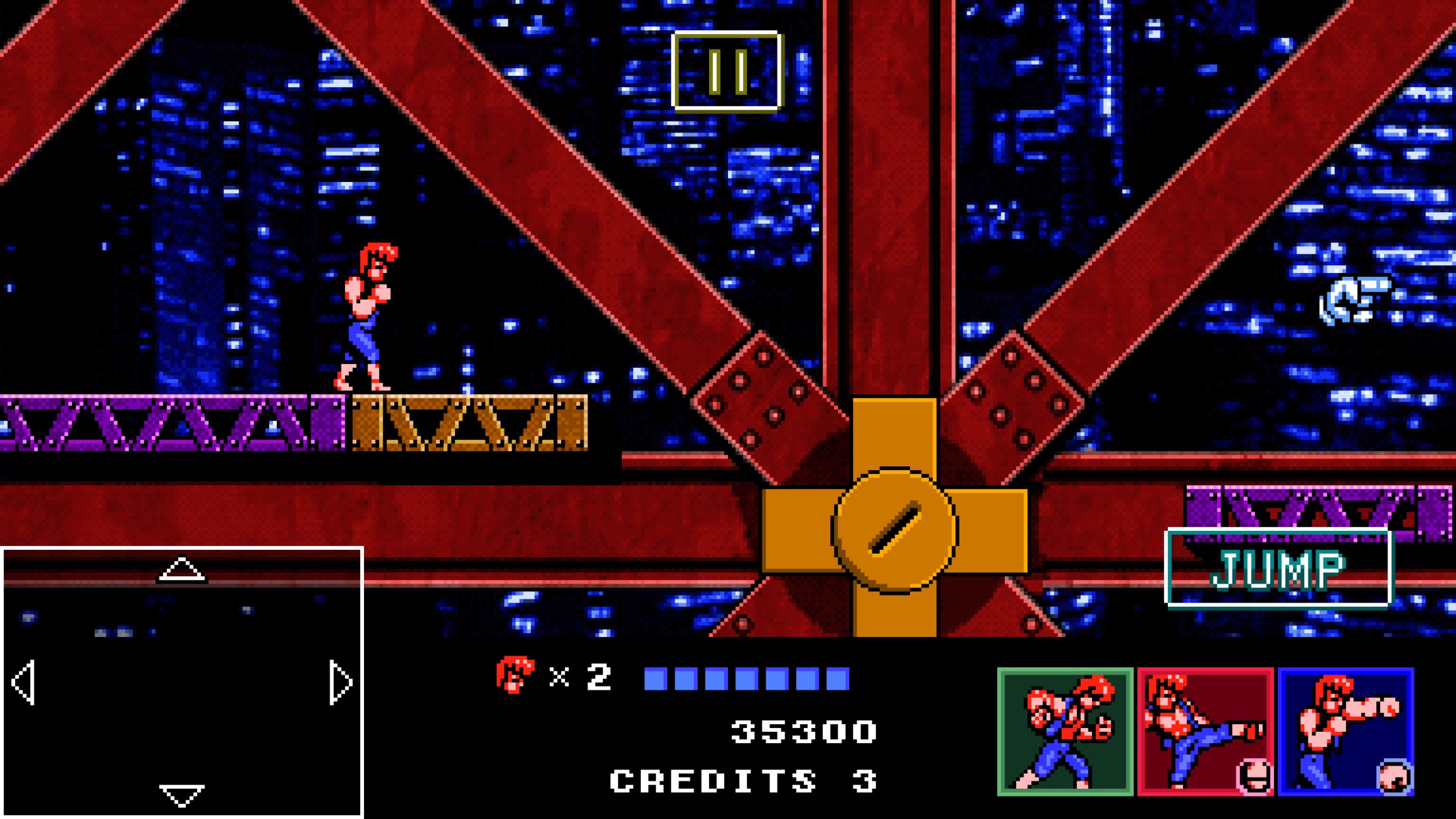

First of all, the game takes more after the NES ports than the arcade series. That’s not too surprising since it is known that Kishimoto wasn’t terribly happy with the results of the publisher’s strict deadlines on Double Dragon 2 and Double Dragon 3‘s arcade versions. Nevertheless, if you were hoping for something that looked like the arcade games or later games like Double Dragon Neon, you’ll want to park those expectations. There are a lot of new sprites, and almost all of the backgrounds are new as well, but there’s also a fair amount of recycling happening here. Linda’s Double Dragon sprite will appear alongside Burnov’s Double Dragon 2 sprite and some brand-new characters, and given the rather disparate styles of each of the NES games, it’s a little jarring in places. The backgrounds are also well beyond what the NES would have been able to do, but I think that’s mostly okay.

There’s a bigger problem than the visual cribbing, however. Double Dragon 4‘s design also calls back to those NES Double Dragon games, with many of its level layouts feeling like they were drawn from Double Dragon 2‘s style in particular. The first few levels are fine if a little linear, occasionally throwing in narrow platforms that you need to jump up or down to in order to proceed. The back half of the game has several platforming sections and other timing-based obstacles that are just as annoying here in 2017 as they were back in the early 1990s. Billy and Jimmy are beat-em-up characters, and as such are not really built for platforming. Trying to hop from a conveyor belt to a moving gear to another moving gear with the brothers’ clunky jumps is unpleasant, as are sections where you have to weave past and leap over heavily-damaging traps.

Granted, these are a very small part of the game’s 12-stage run. But I’m baffled as to why they’re here at all, let alone in such abundance. All I can surmise is that the developers were looking for ways to break up the brawling sections to keep the game fresh. That shouldn’t be necessary, mind you. None of the other genre greats felt the need to insert such ill-fitting sections in their games. They seemed to have confidence that the players would enjoy the battle encounters enough to carry the experience. This gets at another issue with Double Dragon 4, though.

While the player characters have a wealth of moves at their disposal and the enemy variety is impressive, few of the game’s encounters have much impact. Perhaps it’s due to the overly-linear nature of the level design, or maybe it’s that there’s no real need for any tactics beyond jump-kicking and punching enemies when they stand up. Likely a combination, I suppose. Even the bosses are lacking. They deal tremendous damage but they’re easily dispatched with the same techniques you use against every other foe. I lost more lives to the silly platforming segments than I did fighting enemies, and even with those irritating sections, I finished the entire game on my first attempt. Where’s the beef?

Clearing the main game unlocks Tower Mode, where you battle against groups of enemies in single-screen arenas with a single life. Your goal is to get as far as you can, and depending on how well you do, you’ll unlock new characters that you can then take into either Story or Tower Mode. Yes, that means you can play as Abobo in the main game if you want. It’s a fun extra, and some of the enemies have a surprisingly large array of moves to mess around with. The only thing that curbs the excitement is that no matter who you play as, you’re still going to have to take them down the same bumpy road. The platforming sections are especially dreadful with poor old Abobo. Poor guy can’t catch a break.

In some ways, this is a decent port. It runs well, and the virtual controls work nicely. The directional pad is big but accurate, and you get four virtual buttons that produce three types of attacks and your ever-useful jump, arranged in a sensible layout that results in minimal confusion. It’s lacking in other ways, sadly. There’s no iPhone X support, the file size is absurdly bloated (over 1 GB for this?), there’s no two-player support, and I don’t think it even has support for MFi controllers. Granted, it’s cheaper on iOS than it is anywhere else, with the full game unlock IAP set at $2.99. If you don’t have an iPhone X, don’t mind virtual controls, and just want to play Double Dragon 4, this will do you well enough.

Double Dragon 4 isn’t terrible, but it’s not very good, either. For better or worse, it feels like something the Double Dragon team would have cooked up in the early 1990s if they were making a NES-exclusive sequel. In doing that, it not only ignores the significant common-sense improvements the genre has made over the last twenty-five years, but also the very same advances its contemporary competition brought to the fore in the 16-bit era. I’m glad Kishimoto and company got a chance to revisit Double Dragon, but the result in many ways answers the question of how the series lost its shine to begin with.