Hello, gentle readers, and welcome to the RPG Reload. This week, we’re continuing our little monthly project looking at the history of handheld RPGs. That means that we will not be taking a look at a specific RPG from the App Store’s past this time around. Last month, we looked at the various competitors to the Game Boy, including the Game Gear, Wonderswan, and more. This time around, we’re pushing the timeline forward again with a look at the long-awaited follow-up to the Game Boy, Nintendo’s Game Boy Advance. In total, this feature will span twelve columns, each one taking a look at a specific era in handheld RPGs. I hope you enjoy reading them as much as I’ve enjoyed researching and writing them! Please let me know what you think by commenting below, posting in the Official RPG Reload Club thread, or by tweeting me at @RPGReload.

Hello, gentle readers, and welcome to the RPG Reload. This week, we’re continuing our little monthly project looking at the history of handheld RPGs. That means that we will not be taking a look at a specific RPG from the App Store’s past this time around. Last month, we looked at the various competitors to the Game Boy, including the Game Gear, Wonderswan, and more. This time around, we’re pushing the timeline forward again with a look at the long-awaited follow-up to the Game Boy, Nintendo’s Game Boy Advance. In total, this feature will span twelve columns, each one taking a look at a specific era in handheld RPGs. I hope you enjoy reading them as much as I’ve enjoyed researching and writing them! Please let me know what you think by commenting below, posting in the Official RPG Reload Club thread, or by tweeting me at @RPGReload.

It should go without saying that tabletop, computer, console, handheld, and mobile games are all inextricably tied with each other in various ways. To consider how other platforms contributed to handheld RPGs in these articles would grow them well beyond the scope I’m able to deal with. I’ll be mentioning some influences here and there, but this is basically a disclaimer that I’m aware handheld RPGs don’t exist in a vacuum, in spite of the relatively narrow historical focus of these articles.

The History Of Handheld RPGs, Part Five – Pocket Roleplaying, Advanced

While Nintendo’s Game Boy was never at any real risk of losing its hold on the market, it at least had some reasonable competition. Those competitors had little chance of taking control of the market, but companies like SEGA and Bandai were big enough that they could lure away some of Nintendo’s support from third parties, if nothing else. In the end, the killing blow to the Game Boy didn’t come from its rivals, however. It was more a case that after 13 years on the market and at least one miraculous revival, the Game Boy tech was just too familiar and weak to capture further attention from a video game market that had recently popped the cork on the PlayStation 2. While the increased interest in the handheld market from competitors assuredly helped prod things along at Nintendo, a proper Game Boy follow-up had already been pushed back at least a few years past its original intended launch thanks to the surprising success of Pokemon. It was time. The only real surprise was that virtually no one else showed up to the fight this time.

Nintendo had been planning a follow-up to the original Game Boy for quite some time. With the Game Boy’s unusual lifespan, it’s easy to forget that before Pokemon, hardware sales had almost completely dried up. Rumors of something being developed in the UK called Project Atlantis started to appear in game magazines in 1996, well before even the Game Boy Color’s release. The specs of the hardware seemed ludicrous at the time, with the CPU speculated to be a 32-bit 160 MHz ARM processor. Depending on who you believed, this hardware would be able to handle games of quality similar to the 16-bit Super NES or the 32-bit PlayStation. Atlantis was said to be scheduled for release in early to mid-1997.

Of course, that never happened. Pokemon arrived in Japan in February of 1996 and caught fire like few games had before, giving the Game Boy an unprecedented stay of execution. Atlantis went on the backburner and although history is murky on this, the project was apparently scrapped. There are some who believe Atlantis went on to become the eventual successor Nintendo released, mostly due to some architectural similarities, but it’s hard to say if a link is there and to what extent it exists. At any rate, Nintendo instead opted to push a stop-gap color version of the Game Boy to ride out the Pokemon wave. It wasn’t until the year 2000 that Nintendo would finally unveil a true follow-up to the Game Boy.

At Nintendo’s Spaceworld event held in Japan on August 24th, 2000, then-Executive Vice President of Nintendo Atsushi Asada pulled a trick that I’m sure is quite familiar to many TouchArcade readers. He first spoke a bit about Nintendo’s recent business achievements, including the Game Boy finally passing the 100 million sold mark. He then said he was ready to show the audience the new product they came to see, reached into his suit pocket, and pulled out the Game Boy Advance. The system would be released in the first half of the following year for $99.99, with a launch line-up of 10 games in Japan. In some ways, the Game Boy Advance was similar to the rumored Atlantis. It had a color LCD screen, a 32-bit ARM processor (albeit clocked at 16.8 MHz rather than Atlantis’s rumored 160 MHz), and a link port. It was clearly aimed at producing 2D sprite-based games, and at least visually, it was capable of almost anything a stock Super NES could do, and then some.

Granted, that’s not a lot of power next to a PlayStation 2, but for developers who had been used to working with the Game Boy, the Game Boy Advance was incredible. It also served as a good home for developers whose talents or budgets were more comfortably used towards 2D games. The only major complaint anyone had was with regards to the screen. On the stock Game Boy Advance, the screen was very dark and had no light of its own. Hobbyists would correct this failing soon, and Nintendo would do the same later in a different way, but for the time being, most developers opted to compensate with a saturated palette of bright colors. That little quirk aside, the Game Boy Advance was exactly the right system at about the right time.

For RPG developers and fans, the extra advantages it offered were clear. The increased screen resolution and massive color palette allowed for more readable text and finer detail than the Game Boy could handle on its best day. The larger cartridge sizes gave developers a lot more breathing room for their games. Although Nintendo discouraged it, the specs were good enough to allow for ports of Super NES games. The battery life was ridiculously good, which was important for fans of longer games. Nintendo had studied the past well and came to the playground ready to fight. The funny thing is, for a few years, nobody showed up. Oh, Nokia made an extremely ill-advised attempt in 2002 with the N-Gage, and the Neo Geo Pocket Color and Wonderswan Crystal were still around for a little while, but there was no serious threat to the Game Boy Advance for most of its admittedly short life.

That lack of competition proved to be the final piece of the puzzle for the Game Boy Advance. If you wanted to reach the handheld audience, there was only one place for a publisher to go. With 2D taking a temporary nap on consoles after the PlayStation/Nintendo 64 generation, many large game companies had a lot of staff with 2D skills and nowhere to ply them. Basically, the Game Boy Advance was cheap, powerful enough to facilitate fairly complex games, had no serious competitors, and could easily host full-priced ports of games from the 16-bit era. It was also going to have Pokemon games, which made it by default the platform of choice for an entire generation of young gamers. It’s no wonder that even companies which had bad blood with Nintendo climbed over each other to get a license for the platform. No one knew it at the time, but all of the events that transpired from Pokemon‘s fortuitous launch in 1996 onward were coming together to completely change the face of the video game market, particularly in Japan.

As with the Game Boy before it, RPGs started appearing mere months after the system’s launch. I’ll mention now that I can’t be as exhaustive in describing the system’s RPG library as I have been with earlier systems. The genre exploded on handhelds from this point on, so I’ll be sticking to important highlights.

Capcom, of all companies, would lead the charge with a port of their Super NES classic Breath Of Fire, following that up later in 2001 with a port of the second game, and an original RPG spin-off of the Mega Man franchise called Mega Man Battle Network. The ports were nice, of course, but it was Mega Man Battle Network that would end up the winner of that lot, spawning several sequels, a TV series, and spin-offs of its own. It featured a storyline that embraced the contemporary media’s obsession with the Internet, paid homage to the main series by using fast-paced, real-time battles, and threw in a card-collecting system to tap into the Pokemon craze.

Nintendo did their part to lure RPG fans to the platform in the first year, too. They commissioned original RPGs from Shining Force developers Camelot Software and Brownie Brown, a newly-formed Nintendo subsidiary composed largely of ex-Squaresoft employees. While the latter’s project, Magical Vacation, never released outside of Japan, Camelot’s game was released in the US only a few months after its debut in Japan. Golden Sun, released in November of 2001 in North America, ended up being an unexpected hit in the American market. While it had most of the usual faults found in Camelot RPGs, its substantial quest, attractive presentation, enjoyable gameplay systems, and collection aspects helped it stand out in the early GBA line-up. The most notable gameplay mechanics in Golden Sun included a practical magic system, called Psynergy, and collectible Djinni summons. Magic could be used to solve puzzles in the dungeons, while the Djinnis were fun to hunt down and made for great eye candy in battles.

Nintendo did their part to lure RPG fans to the platform in the first year, too. They commissioned original RPGs from Shining Force developers Camelot Software and Brownie Brown, a newly-formed Nintendo subsidiary composed largely of ex-Squaresoft employees. While the latter’s project, Magical Vacation, never released outside of Japan, Camelot’s game was released in the US only a few months after its debut in Japan. Golden Sun, released in November of 2001 in North America, ended up being an unexpected hit in the American market. While it had most of the usual faults found in Camelot RPGs, its substantial quest, attractive presentation, enjoyable gameplay systems, and collection aspects helped it stand out in the early GBA line-up. The most notable gameplay mechanics in Golden Sun included a practical magic system, called Psynergy, and collectible Djinni summons. Magic could be used to solve puzzles in the dungeons, while the Djinnis were fun to hunt down and made for great eye candy in battles.

While it’s not an RPG, I also need to mention Advance Wars, the revival and first-time localization of Intelligent Systems’ long-running Wars series of turn-based strategy games. The game hit it off well with the international audience, priming the pump for a certain other long-running Intelligent Systems series to make its English debut later. While it seems like the Wars series has gone dormant these days, its contributions, direct and otherwise, to the strategy RPG genre should never be forgotten.

2002 saw RPG releases from many major Japanese companies, including Konami, Capcom, the newly-third party SEGA, Electronic Arts, Infogrames, Game Arts, and others. Though these games covered a spread of sub-genres, most of them wisely included at least some sort of collection aspect. Nintendo once again put a strong foot forward with a speedy follow-up to Golden Sun called The Lost Age, which allowed players to use a link cable or a very long password to carry over a cleared save file from the first game. More significantly, Nintendo released the sixth installment of Intelligent Systems’ Fire Emblem series exclusively on Game Boy Advance. Previously a console-only series, Fire Emblem‘s move to handheld heralded a big upcoming shift in the Japanese RPG market. Fire Emblem: The Binding Blade was a major release in a long-running RPG series, and you could only play it on handheld. Fire Emblem would make occasional returns to console in the future, but from here on out, it chiefly became a handheld franchise.

But Nintendo’s biggest card came, at least in Japan, in November of 2002 with the release of Pokemon Ruby and Pokemon Sapphire, the newest generation of Pokemon games. Those games would release a few months later in the rest of the world, and from that point on, the Game Boy Advance never looked back. Pokemon Ruby and Pokemon Sapphire aren’t looked back on as fondly as some of the other games in the series, but it’s easy to see why they had trouble impressing. Virtually everyone involved with Pokemon thought that Gold and Silver would be the last games in the series, so they threw everything into those games that they possibly could. That left them in an awkward position with these next games. Sales were nevertheless quite strong, and helped solidify the Game Boy Advance’s market around the world. Game Freak would release their usual third version, called Pokemon Emerald, the following year, and remakes of the first generation Pokemon games the year after that. Many predicted the Pokemon phenomenon would lose steam around this time, but the sales and interest from fans around the world said otherwise.

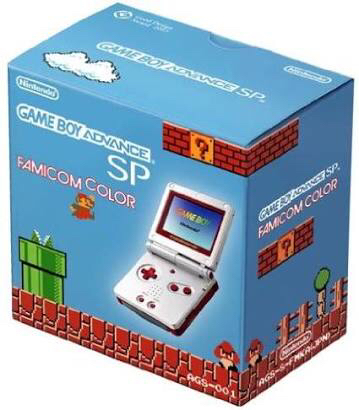

The next year, 2003, was a big one for both the Game Boy Advance and Nintendo on the whole. To start with, Nintendo introduced a new version of the Game Boy Advance. It had a clamshell style design and a front-lit screen, solving the main complaint about the original unit. Using the light bit into the battery life significantly. Luckily, Nintendo had made the bold choice of including a rechargeable battery in the SP, so players didn’t have to worry about buying new batteries all the time. This made longer games like RPGs more palatable as you no longer had to factor in the cost of the batteries it would take to beat them. I’m sure parents rejoiced.

The next year, 2003, was a big one for both the Game Boy Advance and Nintendo on the whole. To start with, Nintendo introduced a new version of the Game Boy Advance. It had a clamshell style design and a front-lit screen, solving the main complaint about the original unit. Using the light bit into the battery life significantly. Luckily, Nintendo had made the bold choice of including a rechargeable battery in the SP, so players didn’t have to worry about buying new batteries all the time. This made longer games like RPGs more palatable as you no longer had to factor in the cost of the batteries it would take to beat them. I’m sure parents rejoiced.

On the software side, big news was afoot as well. After several years of frosty relations between Nintendo and Final Fantasy‘s publisher Squaresoft, the ice finally broke. As usual, it seems like money heals all wounds. Squaresoft had recently announced they would be merging with rival Enix, with the new company Square Enix operating under the leadership of the former Enix. Square Enix saw major sales potential in the handheld market and with Bandai bowing out, Nintendo was the only game in town. For their part, Nintendo needed something to help prop up the struggling Gamecube, particularly in Japan where sales were unusually cool for a Nintendo console. Luckily, the two companies could help each other out. Though the whole Gamecube thing didn’t amount to much, Square Enix and Nintendo’s new relationship would provide significant handheld fruit to the benefit of both companies thereafter.

The first Square releases on the Game Boy Advance were announced to be Final Fantasy Tactics Advance, Sword Of Mana, and Chocobo Land. While the latter was a board game featuring Square’s popular walking dinner special, the other two were of interest to RPG fans. Of the two, Final Fantasy Tactics launched first, releasing in February in Japan and September in North America. While some had guessed it would be a port of the cult hit PlayStation game, it was actually a completely new game. Reactions to the game were mixed, but the game sold very well. It also was an important marker in that it was yet another fully-formed sequel in a major console series, and you could only play it on handhelds. Sword Of Mana, which arrived a few months later respectively in all regions, was less remarkable. It was a remake of the Game Boy Final Fantasy Adventure (Seiken Densetsu) that somehow ended up being worse in almost every way.

The first Square releases on the Game Boy Advance were announced to be Final Fantasy Tactics Advance, Sword Of Mana, and Chocobo Land. While the latter was a board game featuring Square’s popular walking dinner special, the other two were of interest to RPG fans. Of the two, Final Fantasy Tactics launched first, releasing in February in Japan and September in North America. While some had guessed it would be a port of the cult hit PlayStation game, it was actually a completely new game. Reactions to the game were mixed, but the game sold very well. It also was an important marker in that it was yet another fully-formed sequel in a major console series, and you could only play it on handhelds. Sword Of Mana, which arrived a few months later respectively in all regions, was less remarkable. It was a remake of the Game Boy Final Fantasy Adventure (Seiken Densetsu) that somehow ended up being worse in almost every way.

Square Enix would continue to offer support for the Game Boy Advance for years to come, with most of the games coming as a result of the Finest Fantasy For Advance project. With Nintendo’s support, remakes and ports of Final Fantasy, Final Fantasy 2, Final Fantasy 4, Final Fantasy 5, and Final Fantasy 6 came to the Game Boy Advance. In fact, Final Fantasy 6 was one of the last notable releases for the platform in North America, arriving in February of 2007, more than two years after the Nintendo DS’s launch. Besides the Final Fantasy ports, there were a couple of Dragon Quest spin-offs, neither of which made it out of Japan, and to the surprise of many, a Kingdom Hearts spin-off.

Kingdom Hearts: Chain Of Memories released in November of 2004, and it’s important for a lot of reasons. First, we see once again that Square Enix isn’t shy about releasing handheld games that follow up on major console releases. In hindsight, Chain Of Memories wasn’t incredibly important for those following the story of Kingdom Hearts, but at the time, Square was touting it as an important bridge between Kingdom Hearts and the upcoming sequel on PlayStation 2. It also demonstrated that Square wasn’t going to tie any of its properties to a single hardware manufacturer anymore. Finally, it’s also significant in that it was developed by Jupiter, who would go on to create the wonderful The World Ends With You. The combat in Chain Of Memories feels like a prototype of what we would eventually see in that game. So, while the game itself wasn’t of the finest quality, it served a number of purposes.

In North America, 2003 was also a big year in that it saw the first English release of a Fire Emblem game. A series going back to the 8-bit era in Japan, Nintendo had never been confident enough in its potential sales to try localizing any of the games that came before. Of all things, we can apparently thank Super Smash Bros. Melee for the company finally changing their mind. Series characters Marth and Roy appeared in that game and were quite popular, giving Nintendo the nudge they needed to release the seventh game in the series, Fire Emblem: The Sword Of Flame, in English at the end of the year under the title Fire Emblem. Ironically, the game featured neither Marth nor Roy, but looking at the sales, it didn’t seem to hurt any. From this point on, only one release in the series would be skipped over for localization, and it was at a time where the series itself was at risk of being retired.

In North America, 2003 was also a big year in that it saw the first English release of a Fire Emblem game. A series going back to the 8-bit era in Japan, Nintendo had never been confident enough in its potential sales to try localizing any of the games that came before. Of all things, we can apparently thank Super Smash Bros. Melee for the company finally changing their mind. Series characters Marth and Roy appeared in that game and were quite popular, giving Nintendo the nudge they needed to release the seventh game in the series, Fire Emblem: The Sword Of Flame, in English at the end of the year under the title Fire Emblem. Ironically, the game featured neither Marth nor Roy, but looking at the sales, it didn’t seem to hurt any. From this point on, only one release in the series would be skipped over for localization, and it was at a time where the series itself was at risk of being retired.

Rounding out an incredible year for handheld RPG fans, Mario & Luigi: Superstar Saga had a simultaneous release worldwide in November. Developed by AlphaDream, a new developer made up of former Square members who had worked on Super Mario RPG: Legend Of The Seven Stars for the Super NES, Mario & Luigi: Superstar Saga was a lively RPG that saw the famous brothers taking on a new enemy. Like previous Mario RPGs, this game’s combat system features a lot of mini-games and timed button presses, and the humor is laid on thick. Apart from the last boss being an absurd damage sponge, something that would become a hallmark of this series, Superstar Saga is a great RPG that does justice to the Mario brand.

Compared to 2003, the next few years were fairly quiet in terms of major releases. The reason for that, of course, was the late 2004 launch of Nintendo’s new handheld, the Nintendo DS. After its predecessor ran 13 long years without a follow-up, the poor Game Boy Advance got just over three years to itself. The reason for that was the announcement of Sony’s PlayStation Portable, a system so powerful that the Game Boy Advance couldn’t hope to compete. In theory, anyway. In practice, the Game Boy Advance enjoyed a long sales tail that saw it beating the PSP here and there in certain markets. Even the Nintendo DS had issues putting its father to rest in certain markets. It wasn’t until the Nintendo DS had a Pokemon of its very own that the Game Boy Advance finally bowed out.

That’s not to say nothing was released on the Game Boy Advance from 2004 to 2007. On the contrary, there were a lot of RPGs released, especially in Japan. There were ports like Shin Megami Tensei, sequels including Fire Emblem: The Sacred Stones, and original titles such as Riviera: The Promised Land. There were more Mega Man Battle Network games, the Square Enix Final Fantasy ports, and the Pokemon remakes. RPG fans were well-fed, to say the least, even the long-ignored English RPG fans. It was clear, however, that most big projects were moving elsewhere. Most, but not all, because Nintendo still had one more card to play.

Mother, or as it’s known in English, Earthbound, has always been a series whose praise exceeds its sales. It’s also a very personal work of writer Shigesato Itoi, famous in Japan for his witty observations and clever ad slogans. The first two games in the series, Earthbound Beginnings on the NES and Earthbound on the Super NES, both had their share of production issues that nearly prevented them from releasing at all. Yet, their troubles were nothing next to the third game, Mother 3. Originally conceived as a release for the Super NES, it soon moved to Nintendo’s 64DD disk drive for the Nintendo 64. The project ran into a number of troubles both internal and external and ended up being shelved in the year 2000. That was almost the end of it, until the idea came to bring it to Game Boy Advance instead. Development began in 2003, and even scaling down to 2D graphics, the development ran quite long.

The game finally came out in Japan in April of 2006, enjoying fairly strong sales but ultimately making its way to the bargain bins due to overestimated demand. Don’t take that to mean the game was a disappointment, though. On the contrary, it was absolutely incredible, and sits near the top of many RPGs fans’ lists of the best JRPGs ever made. It was just too late to release, unfortunately. The Game Boy Advance died more quickly in Japan than in other regions, which hurts its potential in the home market. Outside of Japan, the late Japanese release meant a localized version would be launching in 2007 or later, something Nintendo just couldn’t justify. Happily for English RPG players, Mother fans are some of the most dedicated in all of gaming. Once it was clear an official version wouldn’t be released, a group got together and made one of the most professional fan translations I’ve ever seen. It’s a great game, and another example of Japan moving major RPG franchises to handhelds.

It was hard to imagine anything could top the Game Boy Advance’s outstanding library of handheld RPGs, accumulated over the course of just a few short years. The peak, however, was yet to come. For now, let’s take a moment to raise our glass to the Game Boy Advance. It was perhaps the first handheld console that allowed for high-quality, full-length RPGs. It proved that major RPG releases were worth pursuing on handhelds. It brought Fire Emblem to America, brought Square back to Nintendo, and it gave us the final installment of the much-loved Mother series. The Game Boy Advance SP popularized the clamshell design that is still used in Nintendo’s handhelds today, and added a rechargeable battery to free us all from the shackles of AAs once and for all. And it did all of that in just a few years.

The best handheld years were still ahead of Nintendo, but there was a storm already brewing off to the side, where almost nobody was looking. In next month’s chapter, we’ll be looking at RPGs for Pocket PCs and feature phones for signs of the coming avalanche.

Shaun’s Five For The Game Boy Advance Era

For each part of this series, I’ll be selecting five notable or interesting titles to highlight. If you’re looking to get a good cross-section of the era in question, these picks are a good place to start.

Golden Sun – Well, realistically, you should play both Golden Sun and Golden Sun: The Lost Age. The first game has a fairly conventional story with some interesting gameplay quirks, like using Psynergy to read people’s minds or solve dungeon puzzles. It’s a little slow at times, but overall, it’s not a bad game at all. The second title is even better, though. Not only is the gameplay more refined, but the story pulls off a pretty neat trick that I haven’t seen in many other games. Play them both, but spare yourself the heartbreak of the third installment, which came out on the Nintendo DS. It ends on a cliffhanger that will never, ever be resolved.

Final Fantasy Tactics Advance – I feel like a lot of the blow back this game got was for being too different from the original. Yes, the story is certainly more family fare than that of the original, but the gameplay has been advanced in a lot of interesting ways. While some might chafe at the Judges and their Laws, I like how they force you to think outside of the box and be prepared for any situation. You need a well-rounded team to stay on top of those restrictions, so you can’t just fall into lazy habits. As an added bonus, the sprite work in this game is gorgeous.

Fire Emblem – While these days it sits in the uncomfortable position of being neither the best Fire Emblem for beginners or experts, Fire Emblem is still an excellent installment in the series. It has a great story with an enjoyable cast of characters, and while the game can be tough as nails, it’s a lot of fun. I really like how you can play through a remixed version of the game that follows the story from the perspective of one of the other major characters in the story, too. That extra gives the game a lot of extra value. The only downside? This is a prequel to a game we never officially got in English, so the ending has a lot of loose threads that you won’t see the results of unless you find some way to play The Binding Blade in a language you understand.

Mario & Luigi: Superstar Saga – For those who felt the Paper Mario games were lacking in essential vitamins and Luigis, Superstar Saga is just the thing. Luigi is by your side throughout the game, and he is wonderful here. The timing-based combat is challenging and rewarding, and the localization is genuinely funny and charming. The last boss is awful, especially if you’re playing the North American version, but that’s a small price to play to enjoy the game up until that point. Still one of the highlights of the Mario & Luigi series and Mario RPGs in general.

Mother 3 – Look, I don’t advocate piracy as a general rule. Please try to get yourself a copy of the original Japanese cartridge if you can. Once you have that, please go and find the fan translated English version of the game somewhere on the Internet. This is all very troublesome, I realize, but it’s worth it. Mother 3 is a fantastic game. I don’t even like Earthbound that much and I still think this game is great. It’s sad, cathartic, and undeniably human in a way that few other RPGs dare to be. The gameplay side of things isn’t quite as remarkable, but the timing-based combo attacks can be fun to learn. If any original RPG had the right to play the wonderful Game Boy Advance off the stage, it was this one.

That’s all for part five of our on-going History Of Handheld RPGs feature. Please let me know what you think by commenting below, posting in the Official RPG Reload Club thread, or by tweeting me at @RPGReload. As for me, I’ll be back next week with a look at Nameless: The Hackers RPG ($7.99). And maybe even a podcast, if the stars align properly. Thanks as always for reading!

Next Week’s Reload: Nameless: The Hackers RPG