Hello, gentle readers, and welcome to the RPG Reload. This week, we’re continuing our little monthly project looking at the history of handheld RPGs. That means that we will not be taking a look at a specific RPG from the App Store’s past this time around. Last month, we explored the earliest origins of pocket RPGs by looking at gamebooks and other interactive fiction. From this month on, we’ll be following handheld RPGs as they entered the digital media, starting with the first half of the Game Boy’s life. In total, this feature will span twelve columns, each one taking a look at a specific era in handheld RPGs. I hope you enjoy reading them as much as I’ve enjoyed researching and writing them! Please let me know what you think by commenting below, posting in the Official RPG Reload Club thread, or by tweeting me at @RPGReload.

Hello, gentle readers, and welcome to the RPG Reload. This week, we’re continuing our little monthly project looking at the history of handheld RPGs. That means that we will not be taking a look at a specific RPG from the App Store’s past this time around. Last month, we explored the earliest origins of pocket RPGs by looking at gamebooks and other interactive fiction. From this month on, we’ll be following handheld RPGs as they entered the digital media, starting with the first half of the Game Boy’s life. In total, this feature will span twelve columns, each one taking a look at a specific era in handheld RPGs. I hope you enjoy reading them as much as I’ve enjoyed researching and writing them! Please let me know what you think by commenting below, posting in the Official RPG Reload Club thread, or by tweeting me at @RPGReload.

It should go without saying that tabletop, computer, console, handheld, and mobile games are all inextricably tied with each other in various ways. To consider how other platforms contributed to handheld RPGs in these articles would grow them well beyond the scope I’m able to deal with. I’ll be mentioning some influences here and there, but this is basically a disclaimer that I’m aware handheld RPGs don’t exist in a vacuum, in spite of the relatively narrow historical focus of these articles.

The History Of Handheld RPGs, Part Two – Game Boy’s First Life

When the Game Boy launched in April 1989, it wasn’t the first handheld video game device. It wasn’t even Nintendo’s first handheld video game device, with the extremely popular Game & Watch series selling more than 43 million units across 59 titles from 1980 to 1991. It was, however, the first handheld video game device that would play host to role-playing games. Part of the reason is down to technology, with earlier handheld systems being unable to easily handle the complex systems and graphics that even simple RPGs required. It’s more likely, however, that the main reason was simply that there was no demand for RPGs on prior systems. Western RPG fans at the time weren’t likely to sacrifice the various advantages that home computers offered the genre, while Japanese RPG fans were almost non-existent until the May 1986 release of Dragon Quest 1 sparked a wildfire of interest in the genre. The Game Boy was meant to be a product for the world, of course, but like most Nintendo hardware, its baseline was always designed around appealing to the domestic Japanese market and its train-dependent lifestyle.

When the Game Boy launched in April 1989, it wasn’t the first handheld video game device. It wasn’t even Nintendo’s first handheld video game device, with the extremely popular Game & Watch series selling more than 43 million units across 59 titles from 1980 to 1991. It was, however, the first handheld video game device that would play host to role-playing games. Part of the reason is down to technology, with earlier handheld systems being unable to easily handle the complex systems and graphics that even simple RPGs required. It’s more likely, however, that the main reason was simply that there was no demand for RPGs on prior systems. Western RPG fans at the time weren’t likely to sacrifice the various advantages that home computers offered the genre, while Japanese RPG fans were almost non-existent until the May 1986 release of Dragon Quest 1 sparked a wildfire of interest in the genre. The Game Boy was meant to be a product for the world, of course, but like most Nintendo hardware, its baseline was always designed around appealing to the domestic Japanese market and its train-dependent lifestyle.

It had enough processing power to handle moving sprites around and scrolling backgrounds, even if its screen wasn’t quite up to snuff. Its battery life was incredibly long, offering anywhere from 15 to 30 hours from four AA-type cells. The Game Boy, much like home consoles, allowed players to swap cartridges to play a variety of games. Again, not the first device to allow that, but it’s one part of the package. Those ROM cartridges could pack in a relatively sizable amount of data, and importantly for RPGs, could be equipped with a battery to allow players to save their progress without the need for passwords or other such work-arounds. I can’t express how vital that last point is for the RPG genre, as on the genre’s face, it seems a poor fit for portable play. Being able to quickly save and pick up later remains a vital feature to this day for handheld RPGs, and the Game Boy was able to handle it right out of the gate.

Of course, the hardware was far from being as powerful as it could be. The black-and-white display and the somewhat poor refresh rate of the screen itself sometimes made it look miserly next to its competition, but those aspects kept the system cheap and contributed greatly to its long battery life, both elements crucial to its success. It was also a strangely forward-thinking device, whether its designers realized it or not. The included link port for connecting multiple Game Boy units together would eventually help change gaming itself, albeit later down the road than we’re going to go in this part of our history. Most importantly for our purposes, while its weaknesses caused issues with certain genres, RPGs suffered little for them. The display’s resolution was high enough that considerable detail could be handled with the system’s limited palette, and text was certainly quite readable.

Of course, the hardware was far from being as powerful as it could be. The black-and-white display and the somewhat poor refresh rate of the screen itself sometimes made it look miserly next to its competition, but those aspects kept the system cheap and contributed greatly to its long battery life, both elements crucial to its success. It was also a strangely forward-thinking device, whether its designers realized it or not. The included link port for connecting multiple Game Boy units together would eventually help change gaming itself, albeit later down the road than we’re going to go in this part of our history. Most importantly for our purposes, while its weaknesses caused issues with certain genres, RPGs suffered little for them. The display’s resolution was high enough that considerable detail could be handled with the system’s limited palette, and text was certainly quite readable.

With the dominance Nintendo had over the home console and overall video game market at the time, the company didn’t exactly have to twist arms to get third party companies interested in supporting its newest offering. Eventually just about every third party publisher would put out a Game Boy game, but the bulk of its support early on came from Japanese companies. Such Famicom mainstays as FCI, Kemco, Capcom, Konami, Bandai, Atlus, Jaleco, Taito, and Squaresoft were there in the system’s first year alone, by and large offering the sorts of games they were known for on other platforms. With the RPG genre being among the most popular in Japan at the time, it was only natural for some of those companies to take a swing at making a handheld RPG or two. Taking a quick glance at the list of third parties in the early years, there’s one particular stand-out missing: Enix, the publishers of Japan’s hottest franchise, Dragon Quest. The series would come to handhelds in a big way later on, but until that day, Enix would release only two games for the Game Boy. In 1992, they would release a strategy game called Dungeon Land, while in 1994, they released an action game based on the manga Nangoku Shounen Papuwa-kun. Token efforts, essentially.

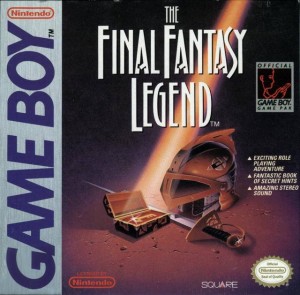

For Squaresoft, the closest thing to a rival Enix had at the time, it’s hard to imagine a better opportunity. Final Fantasy was popular enough on the Famicom, though it was coming off a somewhat rough reception over the unconventional Final Fantasy 2. But it was far from reaching the status of Dragon Quest, meaning Squaresoft had to tiptoe around the genre giant’s releases carefully to avoid being crushed. With the Game Boy, Squaresoft had the chance to become the platform king of Japan’s genre of choice, and they threw themselves into their initial effort pretty hard. Though it ended up being a tight race, Squaresoft ultimately became the publisher of the very first handheld electronic RPG. Makaitoshi SaGa, or The Final Fantasy Legend as it’s known in English, released on December 15th, 1989, a scant two weeks before Kemco’s The Sword Of Hope.

For Squaresoft, the closest thing to a rival Enix had at the time, it’s hard to imagine a better opportunity. Final Fantasy was popular enough on the Famicom, though it was coming off a somewhat rough reception over the unconventional Final Fantasy 2. But it was far from reaching the status of Dragon Quest, meaning Squaresoft had to tiptoe around the genre giant’s releases carefully to avoid being crushed. With the Game Boy, Squaresoft had the chance to become the platform king of Japan’s genre of choice, and they threw themselves into their initial effort pretty hard. Though it ended up being a tight race, Squaresoft ultimately became the publisher of the very first handheld electronic RPG. Makaitoshi SaGa, or The Final Fantasy Legend as it’s known in English, released on December 15th, 1989, a scant two weeks before Kemco’s The Sword Of Hope.

In spite of the title of its 1990 American release, you can probably figure out that The Final Fantasy Legend wasn’t originally a Final Fantasy game at all. Except, it kind of was. I’ve talked before (in RPG Reload File 018) about the oddball Final Fantasy 2 and its equally off-beat designer, Akitoshi Kawazu. He’s a person who has always followed the beat of a drum few can hear besides himself, and his turn on the Final Fantasy series hadn’t quite gone over well. Squaresoft wanted to make a safer sequel with Final Fantasy 3, and that meant Kawazu wasn’t going to be a big part of it. When Square’s president noticed the success of Game Boy and Tetris, he put out the call for his developers to create a game for the new system. Two veterans of the Final Fantasy team answered the call: Koichi Ishii, who we’ll get to shortly, and Akitoshi Kawazu. They were the ones who suggested that Squaresoft Game Boy games should be role-playing games, as they felt that’s what customers would be most interested in.

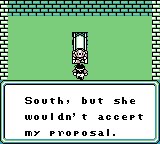

Kawazu’s baby, The Final Fantasy Legend, would come first. Incorporating many of the ideas from Final Fantasy 2 and few new ones, it was nonetheless a pretty straight-forward JRPG in many ways, even adopting Dragon Quest‘s first-person battles over Squaresoft’s typical side-view scenes. The design was carefully crafted around the mobile experience, however. The game’s length was planned to be between six and eight hours, based on nothing more than that being the amount of time it took to fly from Narita Airport to Honolulu. The random encounter rate was increased relative to other Square games to make sure that someone playing the game for five minutes between train stations would have something exciting to do. Crucially, the ability to save at any time outside of combat was added, so that players who needed to quickly stop playing could do so easily. The story, largely written by Kawazu himself, follows a group of heroes who ascending a tower that supposedly leads to paradise. What they find at the end was somewhat surprising at the time, but is such a well-trodden twist by now that it borders on cliche.

In true Kawazu fashion, there are lots of strange elements to the gameplay systems. Characters can be one of three different types: humans, who can only improve their abilities by consuming expensive potions and wielding better gear, mutants, who develop almost like a Final Fantasy 2 character with stat gains based on their actions, and monsters, who can only become stronger by consuming the randomly-dropped meat of a defeated more powerful monster. Also strange, but soon to become a Kawazu trademark, is that your characters have lives. When they fall in battle, they lose a heart, and if they run out of hearts, they’re gone for good. All you can do is bring a new party member at the guild to replace them. You need a lot of money to develop human characters, a lot of luck to develop mutants thanks to their random skill slots, and, well, nothing can really help the monsters. They don’t work very well in the late game, so as much fun as they are to use, I wouldn’t advise it in this installment.

In true Kawazu fashion, there are lots of strange elements to the gameplay systems. Characters can be one of three different types: humans, who can only improve their abilities by consuming expensive potions and wielding better gear, mutants, who develop almost like a Final Fantasy 2 character with stat gains based on their actions, and monsters, who can only become stronger by consuming the randomly-dropped meat of a defeated more powerful monster. Also strange, but soon to become a Kawazu trademark, is that your characters have lives. When they fall in battle, they lose a heart, and if they run out of hearts, they’re gone for good. All you can do is bring a new party member at the guild to replace them. You need a lot of money to develop human characters, a lot of luck to develop mutants thanks to their random skill slots, and, well, nothing can really help the monsters. They don’t work very well in the late game, so as much fun as they are to use, I wouldn’t advise it in this installment.

Kawazu wasn’t working alone on the game, of course. Various team members at Square pitched in, including Final Fantasy 4 lead designer Takashi Tokita, Final Fantasy series composer Nobuo Uematsu, Active Time Battle system designer Hiroyuki Ito, and of course, Koichi Ishii, who was quite busy with his own Game Boy project. That game was Seiken Densetsu: Final Fantasy Gaiden, known in America as Final Fantasy Adventure or Sword Of Mana, and in England as Mystic Quest. While The Final Fantasy Legend was deliberately designed to distance itself from the main Final Fantasy series, Seiken Densetsu was given the rather large honor of being the first official Final Fantasy spin-off. That would last for one whole game before it grew into its own popular series, the loose collection of games united under the moniker of Mana.

As opposed to The Final Fantasy Legend‘s typical turn-based RPG framework with bizarre sub-systems, Final Fantasy Adventure went with an action-RPG format while making use of a lot of familiar elements from more standard JRPGs. It wasn’t the first action-RPG released on Game Boy, with that honor going to Rolan’s Curse the year before, but it was easily the best of the lot, and definitely incorporated more RPG aspects than its competition did. It also tells a much heavier story than most other Game Boy games, full of twists and a lot of sad situations that are only slightly cheapened by the game’s questionable English translation. Between this game and Link’s Awakening, the Game Boy was basically a one-stop shop for melancholy on the road, friends. Like The Final Fantasy Legend, this game allowed the player to save at any time and was quite fun even in short bursts. The game performed well enough to launch a series spanning multiple platforms and a couple of decades. Somehow, only a few of those follow-ups lived up to the quality of this first game.

As opposed to The Final Fantasy Legend‘s typical turn-based RPG framework with bizarre sub-systems, Final Fantasy Adventure went with an action-RPG format while making use of a lot of familiar elements from more standard JRPGs. It wasn’t the first action-RPG released on Game Boy, with that honor going to Rolan’s Curse the year before, but it was easily the best of the lot, and definitely incorporated more RPG aspects than its competition did. It also tells a much heavier story than most other Game Boy games, full of twists and a lot of sad situations that are only slightly cheapened by the game’s questionable English translation. Between this game and Link’s Awakening, the Game Boy was basically a one-stop shop for melancholy on the road, friends. Like The Final Fantasy Legend, this game allowed the player to save at any time and was quite fun even in short bursts. The game performed well enough to launch a series spanning multiple platforms and a couple of decades. Somehow, only a few of those follow-ups lived up to the quality of this first game.

For its part, The Final Fantasy Legend was successful enough to kick off the SaGa series, which still somehow continues to this day in spite of near-constant critical battering throughout its lifetime. The Game Boy would see two more releases in the series, and in a rare case, all three would be released in English. The first two games received pretty spotty translations, but the third was the first work for Ted Woolsey at Square, and he did a pretty good job for the story-heavy game. Final Fantasy Legend 3 would be Squaresoft’s last Game Boy release, launching in Japan in December of 1991 and in America nearly two years later. Their Game Boy line-up was perhaps a victim of its own success. Kawazu and his SaGa series were promoted to the 16-bit Super Famicom, as were Ishii’s Seiken Densetsu sequels. In hindsight, it’s easy to forget just how quickly the Game Boy burnt out before its second wind arrived, but you can clearly spot it in the patterns of game releases.

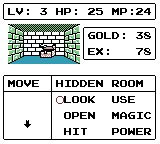

Squaresoft wasn’t the only game in town, though. As I already mentioned, Kemco just narrowly missed being the publisher of the first handheld electronic RPG. Selection: Erabareshi Mono, better known in English as The Sword Of Hope, released only a couple of weeks after The Final Fantasy Legend in Japan, just days before the close of 1989. Yes, that’s right, Kemco. They were there in the beginning, and they’re still here, so let’s at least give them a bit of respect for time served. The Sword Of Hope was developed internally at Kemco, and was only their second RPG on any platform. That said, there’s a bit of a familiar air to it. Kemco had enjoyed major success with their Famicom ports of the MacVenture games, with Shadowgate in particular serving as one of their biggest hits early on. That’s as good an explanation as any for why Sword Of Hope ended up being a hybrid of adventure game and RPG. Basically, imagine a considerably fairer and simpler version of Shadowgate where you stand a chance of getting pulled into a turn-based RPG battle after every action, and you’ll have the right idea.

The Sword Of Hope is actually quite good for such an early release. The puzzles are pretty easy to figure out and certainly less punishing than the MacVenture games, and while the battle system is generic in all respects save its unusual damage calculations, it works well enough. The encounter rare is perhaps a little high for my liking, but it certainly keeps you on your toes. Like Squaresoft’s games, The Sword Of Hope can probably be cleared in under ten hours, which is just about the right amount of time given what the game offers. It’s not as savvy to the hardware as The Final Fantasy Legend, though. The game cartridge doesn’t include battery back-up, so saving your progress requires you to return to a shaman near the game’s starting point and get a password. Not terribly convenient when you’re out and about. Apart from that little bit of bad planning, The Sword Of Hope is a solid game, lacking the roughness of The Final Fantasy Legend, but also lacking its bold ideas. The English localization is a bit odd, but it has a certain charm to it. This game received a sequel a few years later, and at least one other Kemco game used its engine, the 1990 Japan-only release Nekojara Monogatari.

The Sword Of Hope is actually quite good for such an early release. The puzzles are pretty easy to figure out and certainly less punishing than the MacVenture games, and while the battle system is generic in all respects save its unusual damage calculations, it works well enough. The encounter rare is perhaps a little high for my liking, but it certainly keeps you on your toes. Like Squaresoft’s games, The Sword Of Hope can probably be cleared in under ten hours, which is just about the right amount of time given what the game offers. It’s not as savvy to the hardware as The Final Fantasy Legend, though. The game cartridge doesn’t include battery back-up, so saving your progress requires you to return to a shaman near the game’s starting point and get a password. Not terribly convenient when you’re out and about. Apart from that little bit of bad planning, The Sword Of Hope is a solid game, lacking the roughness of The Final Fantasy Legend, but also lacking its bold ideas. The English localization is a bit odd, but it has a certain charm to it. This game received a sequel a few years later, and at least one other Kemco game used its engine, the 1990 Japan-only release Nekojara Monogatari.

That year would also see the release of a few other RPGs. It kicked off with the release of Rolan’s Curse, an action-RPG that was a naked Zelda clone in most respects save the presence of a two-player mode that used the link cable. Nihon Falcom’s landmark action-RPG Dragon Slayer got a port in the summer, while Japan Art Media kicked off their briefly-popular Japan-only Aretha series of traditional JRPGs. Capcom’s excellent Gargoyle’s Quest also arrived part-way through the year, though its RPG elements were very light. Final Fantasy Legend 2 closed out the year, following up the first game with a much better overall package. While things were picking up steam in terms of releases, nothing from 1990 really jumped out in terms of innovation.

The following year, 1991, ended up having the most RPG releases of any year for quite some time. There were a couple of sequels in the form of Final Fantasy Legend 3 and Aretha 2, along with Squaresoft’s Final Fantasy Adventure spin-off. Konami made the scene with a new Ganbare Goemon game and a roguelike called Cave Noire. Other big names that joined the genre include Taito with Knight Quest and Hudson with Momotaro Densetsu Gaiden, both mechanically fairly typical JRPGs. Of historical note, April 1991 saw the release of the very first Super Robot Taisen game in Japan, launching an incredibly popular series of strategy-RPGs that is still prosperous today. Also of note is that this is the first year where we saw the release of some Western-developed Game Boy RPGs. Sculptured Software’s Robin Hood: Prince Of Thieves, based on the hit Kevin Costner film of the same name, was of questionable quality, but Maxis’s Mysterium was quite an interesting adventure-RPG.

If Maxis isn’t enough star power for you, Origin Systems released their own internally-developed Ultima spin-off on the Game Boy in 1991. Titled Runes Of Virtue, it was a Zelda-inspired action-adventure designed by Dave “Dr. Cat" Shapiro and Gary Scott Smith. Like Rolan’s Curse, two players could play Runes Of Virtue simultaneously via the system link cable. Granted, both players needed their own hardware and copies of the game, but it’s still a pretty cool feature. The Avatar doesn’t even make an appearance in the game, instead allowing you to control one of his famous companions on a quest to recover the eight Runes of Virtue from the famous dungeons of Sosaria. Of course, where there’s Ultima, there’s also Wizardry, albeit only in Japan this time around. Wizardry Gaiden, the first ever Wizardry spin-off, was developed and released in Japan only, closing out 1991’s RPG line-up.

Things started to cool down in 1992. Japan saw the follow-up to The Sword Of Hope, along with Aretha 3, Dragon Slayer Gaiden, Rolan’s Curse 2, and Wizardry Gaiden 2. All were very safe sequels, adding very little to the previous installments in their respective series. Other familiar faces included Data East’s Glory Of Heracles: The Living Gods, and Atlus’s Megami Tensei Gaiden: Last Bible, known in English as Revelations: The Demon Slayer. The latter is notable for being the first handheld RPG with a monster-catching mechanic. That’s probably why it was eventually released in English, nearly seven years later. The only truly original release of 1992 was Namco’s Great Greed, a bizarre RPG that had active battles and no menus. It was a pretty poor game with some interesting ideas that somehow got an English release.

The following year, 1993, saw only five new releases in the genre, but a couple of them were pretty interesting. In terms of sequels, there were Last Bible 2 and Ultima: Runes Of Virtue 2. Technos Japan released a Game Boy port of their Japan-only Famicom River City Ransom spin-off that took place in samurai-era Japan. In addition, there were a couple of interesting board game variants released. Hudson’s Castle Quest was like a twisted fusion of chess and card games, while Irem’s Japan-only Undercover Cops: Gaiden was a dice-based board game with RPG battles and mechanics. Those unusual titles and safe sequels would have to hold over handheld RPG fans for a while, with no new releases in the genre in 1994, and only a single RPG, Atlus’s Another Bible, released in 1995.

To be fair, the Game Boy had been out for six years by that point. Sales of both hardware and software had slowed to the point where most releases weren’t much more than statistical noise. The technology was already a bit dated when the Game Boy launched, and developers had pushed it as hard as they could. Surely it was time to send the system off into the night and replace it with some new hardware. Even Nintendo was scraping the barrel at this point, tossing out Game Boy ports of 16-bit games that the system was ill-equipped to handle, supplementing them with the odd Tetris variant, Game & Watch collection, and low-budget experimental game to pad things out. Indeed, it looked like Nintendo would finally retire their little black-and-white handheld that could, until something completely unplanned-for happened.

One of those low-budget experimental games had to go and change the world of gaming forever.

Shaun’s Five For The Game Boy’s First Life

For each part of this series, I’ll be selecting five notable or interesting titles to highlight. If you’re looking to get a good cross-section of the era in question, these picks are a good place to start.

Final Fantasy Legend 2 – Look, you could play The Final Fantasy Legend if you really want to see how things started. It’s not bad, even if it is pretty weird. But I’d give a much stronger recommendation to Final Fantasy Legend 2, which offers nearly every strength of the first game in a much more enjoyable package. Offering a big quest with a lot of variety and interesting quirks, this is probably the best pure JRPG experience on the Game Boy in this era. The third game in the series would go on to shave off more of the edges, but while I enjoy it, I feel like it ended up cutting away a little too much of the personality found in this sub-series. Plus, this is the only RPG where you have to stop banana smugglers while on a journey to find out why your dad jumped through the window one night and never came back. You can’t argue with that!

Final Fantasy Adventure – This, on the other hand, is probably the best RPG in the broad sense during the first Game Boy period. The action can be a little clunky, but the quest is a lot of fun. The sequel, Secret Of Mana, would build strongly on this game’s foundations, but there’s enough in common between the two that if you for some reason are a Mana fan and haven’t played Final Fantasy Adventure, you really should. The Game Boy Advance remake, Sword Of Mana, is a decent enough game in its own right, but I actually prefer the humble Game Boy original for its efficient, compact nature. While the original isn’t as complex as the remake, there are still lots of weapons to use, plenty of cool bosses to fight, and a nice snappy pace to it all that means you’ll rarely find yourself bored. It should be interesting to see which version the upcoming mobile remake takes most after.

The Sword Of Hope – Kemco’s first handheld RPG, and in some ways one of their better ones. Fusing turn-based RPG combat with adventure game elements clearly inspired by the MacVenture ports they were famous for, The Sword Of Hope might not be as mechanically interesting a game as The Final Fantasy Legend, but I personally feel it’s a more enjoyable one. English gamers looking for a somewhat traditional turn-based RPG without Akitoshi Kawazu’s bizarre design sensibilities don’t really have many other places to turn in this era, but for a default winner, The Sword Of Hope is still quite good. The only big gripe I have with it is the lack of a battery save. You’ll have to head back to the shaman near the start of the game to get a password every time you want to stop playing.

Ultima: Runes Of Virtue – Okay, yes, this barely qualifies as an RPG. That said, it’s a decent action-adventure spin-off of one of the grandparents of the genre, and at least deserves some respect for offering two-player simultaneous play almost a decade before The Legend Of Zelda tinkered with the idea. While it doesn’t offer even a lick of the complexity of the main series, it’s still a pretty competent adventure, with lots of fun puzzles to solve and tough bad guys to fight. It’s also kind of fun to see popular Ultima series characters in a more light-hearted and family-friendly title. A particular highlight for me was coming across the big bad of the game, the Black Knight, in an early dungeon. Having boxed himself in while apparently trying to solve a puzzle, all he can do is utter impotent threats at you while you continue on your way. If you can somehow manage to take advantage of the multiplayer mode, Runes Of Virtue is a pretty good time even today.

Wizardry Gaiden: Suffering Of The Queen – I’m cheating a little bit here since this one isn’t officially available in English, and it’s downright impenetrable if you can’t read Japanese, but I think this is a pretty noteworthy game in a relatively meager selection. First of all, it’s the first Wizardry game not developed by Sir-Tech, the first created entirely by Japanese developers for Japanese players. Foreshadowing the eventual fate of the series, Suffering Of The Queen is just as painfully difficult and merciless as Wizardry at its meanest, but with much nicer aesthetics than the main series had at this point. The three Wizardry Gaiden games on the Game Boy are probably the biggest RPGs available in the platform’s early years in terms of sheer length, and they have a neat fan-fiction quality to them that the Japanese Wizardry games would eventually grow out of. That said, it’s Wizardry through and through mechanically, so tread carefully if you dare.

That’s all for part two of our on-going History Of Handheld RPGs feature. Please let me know what you think by commenting below, posting in the Official RPG Reload Club thread, or by tweeting me at @RPGReload. As for me, I’ll be back next week to kick of Hallowe’en Month in the RPG Reload with a look at Tin Man’s Gamebook Adventures 2: The Siege Of The Necromancer ($5.99)! Thanks as always for reading!

Next Week’s Reload: Gamebook Adventures 2: The Siege Of The Necromancer