Machinarium [$4.99] is a treasure, judiciously and efficiently designed, with not a single pencil-drawn sprite out of place.

Machinarium [$4.99] is a treasure, judiciously and efficiently designed, with not a single pencil-drawn sprite out of place.

It was worthing playing on the PC two years ago, it will be worth playing on the PlayStation 3 later this year, and it’s worthing playing on your iPad 2 right now.

The “story" of Machinarium — Amanita Design’s first full-length effort — is unobtrusive and elegant, told entirely through the unnamed protagonist-bot’s thought bubbles and context clues. There is no human speech to parse, no dialogue trees to navigate, no lengthy exposition to ignore — Jakub Dvorsky and his team have a laser-sighted focus on puzzle design.

And what puzzles they are! Machinarium features a mix of traditional logic problems and modern, multi-step inventory manipulation puzzles that, by and large, fall into the range where challenge and critical thinking intersect. The result is a game that feels organic and internally consistent, with none of the arbitrary, “guess-what-the-designer-wants" logic that so often plagues puzzle games.

If you do happen to get stuck — and that’s ok! — there is a two-fold hint system that should give you a nudge in the right direction: a hint system, and a full-blown (and beautifully illustrated) in-game walkthrough. The rub: the hint system is generally pretty limited, and access to the walkthrough is blocked by an intentionally awful LCD-screen shmup, which is boring and time-consuming enough to discourage the mentally lazy. (One of the iPad 2 version’s quirks is that it’s, y’know, impossible to alt+tab to a walkthrough, adding yet another barrier for those inclined to cut corners.)

When touch screens became a viable input device for the games industry, the consensus was that point-and-click adventures would be a natural fit. This is particularly true for Machinarium: Amanita decided to limit players’ range of motion to a few actionable hotspots in each area. In other words, Machinarium dispels the need for super-precision touch controls — the game is designed to require as little movement as necessary.

When touch screens became a viable input device for the games industry, the consensus was that point-and-click adventures would be a natural fit. This is particularly true for Machinarium: Amanita decided to limit players’ range of motion to a few actionable hotspots in each area. In other words, Machinarium dispels the need for super-precision touch controls — the game is designed to require as little movement as necessary.

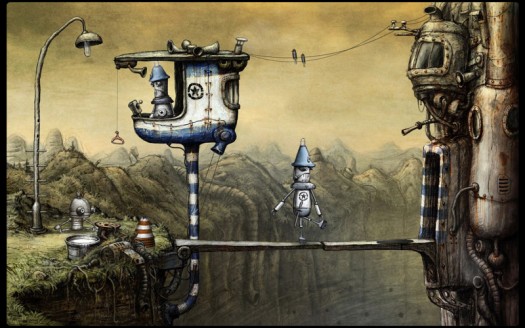

Machinarium, as a whole, is remarkably tidy. It begins with an unnamed protagonist being dumped, rather unceremoniously, on the outskirts of a city whose skyline is dominated by an ominous spire; it ends with a flashback of the events that set the game in motion in the first place. The puzzles employ a similar rolling structure: each puzzle is discrete and self-contained, but the game as a whole is tightly paced and given momentum by a set of smart, complementary design choices.

First: solving any given puzzle in Machinarium generally results in the acquisition of another inventory item that — unbeknownst to the player — will be critical to a later scenario. Secondly: though the town square acts as a hub for the gameworld, the bulk of Machinarium’s puzzles take place inside individual rooms or buildings, i.e. on a single screen. The result is that players enter each area already armed with the necessary tools and aren’t forced to travel very far to solve puzzles. Like a shark, Machinarium thrives because its design encourage progress, not stagnation — every step.

My only real hiccup with Machinarium’s high-level dynamics is that the gameworld doesn’t always do enough to inform or motivate the player. For example, an early puzzle tasks players with helping a group of musicians fix their instruments, but the player has no real reason to help them except that they happen to exist in the gameworld. The game’s sparse narrative components are great when it comes to contextualized story telling, but they don’t particularly account for the player’s need to, say, fix someone’s didgeridoo. Instead, it’s design by tautology: Machinarium is a puzzle game, so it should include puzzles.

Everything else in the game is beautifully realized. The puzzles, full of circuitboards, waterworks, and mechanical tinkering; the protagonist’s evocative animation; the mournful soundtrack — all of these things exist to sell the idea that a world populated entirely by robots could be plausible, and that this particular robot has something important to contribute to it. Nevertheless, there are several moments — even after you discover the game’s central conflict — that are aren’t necessarily tethered to any kind of narrative or in-game logic: puzzles are solved because they simply exist, not because it’s clear that they somehow contribute to one robot’s quest to save his city from … well, bullies.

Bullies, of all things. How quaint, right?

And maybe that’s why we had to help those poor, broke musicians — because Amanita Design hopes that we’re just nice people. That Machinarium is, give or take, a beautifully evocative story about playground bullying should indicate the kind of charming, understated game it is. Even the name, Machinarium, suggests a mysterious, whimsical place — I do hope you explore it.